Eastern Partnership

| |

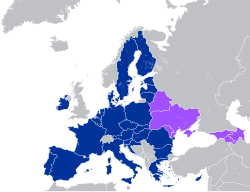

European Union Non-EU members of the Eastern Partnership | |

| Formation | 7 May 2009 |

|---|---|

| Founded at | Prague |

| Type | European External Action Service initiative |

| Headquarters | Brussels, Belgium |

| Location | |

| Membership |

|

| Website | Website |

The Eastern Partnership (EaP) is a joint initiative of the European Union, together with its member states, and six Eastern European countries. The EaP framework governs the EU's relationship with the post-Soviet states of Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine.[1] The EaP is intended to provide a forum for discussions regarding trade, economic strategy, travel agreements, and other issues between the EU and its Eastern European neighbours. It also aims at building a common area of shared values of democracy, prosperity, stability, and increased cooperation.[1] The project was initiated by Poland and a subsequent proposal was prepared in co-operation with Sweden.[2] It was presented by the foreign ministers of Poland and Sweden at the EU's General Affairs and External Relations Council in Brussels on 26 May 2008.[3] The Eastern Partnership was inaugurated by the EU in Prague, Czech Republic on 7 May 2009.[4]

The first meeting of foreign ministers in the framework of the Eastern Partnership was held on 8 December 2009 in Brussels.[5]

History

[edit]The Eastern Partnership (EaP) was established as a specific Eastern dimension of the European Neighbourhood Policy, which contains both a bilateral and multilateral track.[6] The Eastern Partnership complements the Northern Dimension and the Union for the Mediterranean by providing an institutionalised forum for discussing visa agreements, free trade deals, and strategic partnership agreements with the EU's eastern neighbours, while avoiding the controversial topic of accession to the European Union. Its geographical scope consists of Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine.[7] Unlike the Union for the Mediterranean, the Eastern Partnership does not have its own secretariat, but is controlled directly by the European Commission.[8]

Riga, May 2015

In May 2008, Poland and Sweden put forward a joint proposal for an Eastern Partnership with Ukraine, Moldova, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia, with Russia and Belarus participating in some aspects. Eventually, Belarus joined the initiative as a full member, while Russia does not participate at all. The Polish foreign minister Radosław Sikorski said "We all know the EU has enlargement fatigue. We have to use this time to prepare as much as possible so that when the fatigue passes, membership becomes something natural"[9] It was discussed at the European Council on 19 and 20 June 2008, along with the Union for the Mediterranean.[10] The Czech Republic endorsed the proposal completely, while Bulgaria and Romania were cautious, fearing that the Black Sea Forum for Partnership and Dialogue and the Organization of the Black Sea Economic Cooperation could be undermined. Meanwhile, Germany, France, and others were not happy with the possibility that the Eastern Partnership could be seen as a stepping stone to membership (especially for Ukraine), while Poland and other Eastern states have explicitly welcomed this effect.[11]

The Eastern Partnership was officially launched in May 2009 when the Czech Republic invited the leaders of the six members of the initiative. Meanwhile, Germany attended the summit to signal their alarm at the economic situation in the East. Russia accused the EU of trying to carve out a new sphere of influence, which the EU denied, stating that they were "responding to the demands of these countries...and the economic reality is that most of their trade is done with the EU".[12]

Member States

[edit]The Eastern Partnership consists of the following 27 EU member states and the 6 Eastern European post-Soviet states:

- EU member states

- Non-EU members

In addition, the above members, except Belarus, further participate in the Council of Europe and the Euronest Parliamentary Assembly in which these states forge closer political and economic ties with the European Union.

The participation of Belarus in the Eastern Partnership and their President Lukashenko, who has been described as authoritarian, at a summit in 2009 was the subject of debate.[13] On 30 September 2011 Belarus seemingly withdrew from the initiative because of: "unprecedented discrimination" and a "substitution" of the principles on which it was built two years ago.[14] However three days later Foreign Minister of Belarus Sergei Martynov refuted this.[15]

On 28 June 2021, the Belarusian Ministry of Foreign Affairs confirmed that Belarus would suspend its membership in the Eastern Partnership.[16]

Institutions and aims

[edit]

The Eastern Partnership is a forum aiming to improve the political and economic trade-relations of the six Post-Soviet states of "strategic importance" – Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova, Ukraine with the European Union.[13] Promotion of human rights and rule of law in former Soviet states has been reported to form the "core" of the policy of the Eastern Partnership.[17] The EU draft of the EaP states that: "Shared values including democracy, the rule of law, and respect for human rights will be at its core, as well as the principles of market economy, sustainable development and good governance." The Partnership is to provide the foundation for new Association Agreements between the EU and those partners who have made sufficient progress towards the principles and values mentioned. Apart from values, the declaration says the region is of "strategic importance" and the EU has an "interest in developing an increasingly close relationship with its Eastern partners..."[18]

The inclusion of Belarus prompts the question whether values or geopolitics are paramount in the initiative. EU diplomats agree that the country's authoritarian president, Alexander Lukashenko, has done little to merit involvement in the policy at this stage. But the EU fears Russia will strengthen its grip on Minsk if it is left out.[19] There are plans to model the concept on the Stabilisation and Association Process used by the EU in the Balkans, including a possible free trade area encompassing the countries in the region, similar to BAFTA or CEFTA. A future membership perspective is not ruled out, either.[20]

Eastern Partnership Cooperation: Priority Areas

[edit]The key focus of the EU engagement within the Eastern Partnership includes the achievement of tangible results for the citizens in the partner countries. The pursuit of tangible outcomes has resulted in 20 deliverables of Eastern Partnership cooperation for 2020.[1] They were developed in close consultation with the stakeholders, and include the following:

- Modernised transport connections through the Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T);

- Increased political ownership of energy efficiency;

- Easier access to finance for SMEs, including to lending in local currency;

- Establishing ways of reducing mobile telephony roaming tariffs between partners by conducting a study;

- Increased trade opportunities;

- Greater outreach to grassroots Civil Society Organizations; and,

- More support for youth.[1]

A joint working document "Eastern Partnership – focusing on key priorities and deliverables" drafted by the Commission and EEAS details the objectives across the five priority areas of cooperation agreed at the Eastern Partnership Summit in Riga in 2015:[21]

- Stronger governance: Strengthening institutions and good governance

- Stronger economy: Economic development and market opportunities

- Better connectivity: Connectivity, energy efficiency, environment and climate change

- Stronger society: Mobility and people-to-people contacts

- Involvement of broader society, gender and communication[1]

Financing

[edit]The EC earmarked €600 million for the six partner countries for the period 2010–13 as part of the European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument, constituting about a quarter of the total funding available to the Eastern Partnership countries in that period. The programme had three main purposes: Comprehensive Institution Building programmes, aimed at supporting reforms (approximately €175 million); Pilot regional development programmes, aimed at addressing regional economic and social disparities (approximately €75 million); and Implementation of the Eastern Partnership, focusing on democracy, governance and stability, economic integration and convergence with EU policies, energy security, and contacts between people with the aim of bringing the partners closer to the EU (approximately €350 million).[22]

In December 2010, the European Investment Bank established the ″Eastern Partnership Technical Assistance Trust Fund″ (EPTATF).[23] It includes the ″Eastern Partnership Internship Programme″ which is open to students who are nationals of Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Moldova, or Ukraine.[24]

In 2021, a new aid package was given to the EU's six Eastern Partnership countries, where Ukraine received €1.9 billion, Azerbaijan €140 million, and Armenia €2.6 billion. In particular, the aid package to Armenia was 62 percent more than previously promised.[25]

Euronest Parliamentary Assembly

[edit]Established in 2011 as a component of the Eastern Partnership, the Euronest Parliamentary Assembly is the inter-parliamentary forum in which members of the European Parliament and the Eastern Partnership participate and forge closer political and economic ties with the EU. The Assembly gathers once a year, meeting locations alternate between an Eastern Partnership country and one of the European Parliament places of work (Brussels, Luxembourg or Strasbourg).

Prospect of EU membership

[edit]In December 2019, following the eighth Euronest Parliamentary Assembly, a resolution was passed by all members outlining various EU integration goals to be achieved by 2030. The resolution affirms that the process of EU enlargement is open to Eastern Partnership member states and that future enlargement of the EU will be mutually beneficial for both the EU and Eastern Partnership members.[26]

In June 2020, European lawmakers called for the creation of a common economic space between the EU and the six members of the Eastern Partnership, as part of a process of gradual integration into the EU. The European Parliament passed the motion which was supported by 507 MEPs, with 119 voting against and 37 abstaining. The motion also confirmed that the Eastern Partnership policy can facilitate a process of gradual integration into the EU.[27]

Eastern Partnership and EU-Ukraine bilateral relations

[edit]

Ukraine is one of six post-Soviet nations to be invited to co-operate with the EU within the new multilateral framework that the Eastern partnership is expected to establish. However, Kyiv pointed out that it remains pessimistic about the "added value" of this initiative. Indeed, Ukraine and the EU have already started the negotiations on new, enhanced political and free-trade agreements (Association and Free-Trade Agreements). Also, there has been some progress in liberalising the visa regime despite persistent problems in the EU Member States' visa approach towards Ukrainians.[citation needed]

That is why Ukraine has a specific view of the Eastern Partnership Project. According to the Ukrainian presidency, it should correspond, in case of his country, to the strategic foreign policy objective, i.e. the integration with the EU.[28][29] Yet, the Eastern Partnership documents (the European Council Declaration of May 2009)[30] do not confirm such priorities as political and economic integration or lifting visas.

Ukraine has expressed enthusiasm about the project. Ukraine deputy premier Hryhoriy Nemyria said that the project is the way to modernise the country and that they welcome the Eastern Partnership policy, because it uses 'de facto' the same instruments as for EU candidates.[31]

Under the Eastern Partnership, Poland and Ukraine have reached a new agreement replacing visas with simplified permits for Ukrainians residing within 30 km of the border. Up to 1.5 million people may benefit from this agreement which took effect on 1 July 2009.[32]

Relationship with Russia

[edit]Russia has expressed strong concerns over the Eastern Partnership,[33] seeing it as an attempt to expand the European Union's "sphere of influence". Russia has also expressed concerns that the EU is putting undue pressure on Belarus[34] by suggesting it might be marginalised if it follows Russia in recognising the independence of the Georgian breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. "Is this promoting democracy or is it blackmail? It's about pulling countries from the positions they want to take as sovereign states", Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov has stated.

Sweden, the co-author of the Eastern Partnership project together with Poland, rejected Mr Lavrov's position as "completely unacceptable". "The Eastern Partnership is not about spheres of influence. The difference is that these countries themselves opted to join", Swedish foreign minister Carl Bildt said at the Brussels Forum. The EU's position on Georgia is not 'blackmail' but "is about upholding the principles of the EU and international law, which Russia should also be respecting", he added.[31]

In November 2009, Russian President Dmitry Medvedev dismissed the Eastern Partnership as useless: "Frankly speaking, I don't see any special use (in the program) and all the participants of this partnership are confirming this to me". However a few days later Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said that Russia does not rule out joining the EU's Eastern Partnership programme.[35] Russia maintained its opposition towards the EPP. For instance, after the Warsaw Summit 2011 of the EPP, Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin stated that due to the economic crisis in the EU, Ukraine would probably not join the EU. Instead of joining the EU, Putin offered a Russia – Ukraine relationship which he said would provide a more competitive and productive economic process.[36]

In May 2015, President of the European Council Donald Tusk stated that Russia was "[compensating for] its shortcomings by destructive, aggressive and bullying tactics against its neighbours" while German Chancellor Angela Merkel said that "the EU makes a crystal clear difference with Russia. We accept that the different Eastern Partnership nations can go their own way and we accept these different ways."[37] Finnish Prime Minister Alexander Stubb stated that "It is the prerogative and right of every independent and sovereign state to choose which club it wants to belong to."[38]

Eastern Partnership Civil Society Forum

[edit]Founded during the Prague Eastern Partnership Summit in 2009, the Eastern Partnership Civil Society Forum (EaP CSF) is an integral part of the Eastern Partnership program and creates a significant and institutional platform for civil society organisations to monitor and discuss the developments regarding democracy building and human rights development in the six partnership countries.[39] The EaP CSF consists of six national platforms and five thematic working groups, which are represented by an annually elected Steering Committee composed of 13 members. The Secretariat of the EaP CSF is based in Brussels. The EaP CSF meets annually to discuss the latest developments and to set their working programme. The first meeting took place in Brussels in 2009. The last EaP CSF Civil Society Summit meeting – which continued the tradition of its preceding 16 Annual Assemblies - took place in Vienna in November 2024. During the meeting, 90 civil society organisations from the EaP countries and the EU adopted a resolution detailing key recommendations on the future of the EaP region and policy.[40]

The EaP CSF aims to support the effective participation of civil society from EaP and EU countries in the process of planning, monitoring and implementing the Eastern Partnership policy. It maintains a dialogue with EU and EaP decision makers to democratically transform the EaP countries and guarantee their integration into the EU.

In 2011, the EaP CSF launched the Eastern Partnership Index, a data-driven monitoring tool used to inform policy-making.[41] It tracks, on a biennial scale, the reform journey of the six Eastern Partnership countries towards sustainable democratic development and European integration.

The EaP CSF has actively advocated for greater political and financial support to civil society in the Eastern partnership, in light of their role in supporting democratisation and rule of law reforms. It has also actively campaigned for an EU response to the human rights situation in Azerbaijan and Belarus.[42] It also monitors the progress on the Moldovan, Ukrainian and Georgian candidacies to the EU.

As of January 2025, the EaP CSF counts over 1,200 member organisations and remains an official interlocutor of EU institutions and EaP partner countries in the EaP architecture. A similar set up is unique for the EaP region, given that no similar platform exists for Western Balkans and Southern Neighbourhood.The EaP CSF provides a framework for transmitting European values and norms. As a result, some scholars have attributed a socialisation function to the Forum, whereby norms sponsored by the European Union are internalised by participating civil society organisations.

Summits

[edit]- 1st Eastern Partnership Summit in Prague in May 2009[43]

- 2nd Eastern Partnership Summit in Warsaw in September 2011[44]

- 3rd Eastern Partnership Summit in Vilnius in November 2013[45][46]

- 4th Eastern Partnership Summit in Riga in May 2015[47]

- 5th Eastern Partnership Summit in Brussels in November 2017[48]

- 6th Eastern Partnership Summit in Brussels in December 2021[49]

Criticism

[edit]Although the Eastern Partnership was inaugurated on 7 May 2009, academic research critically analysing the policy became available by early 2010 with the findings from a UK research project, funded by the Economic and Social Research Council, examining the EU's relations with three Eastern Partnership member states, Belarus, Ukraine, and Moldova notes both conceptual and empirical dilemmas.[50] First, conceptually the EU has limited uniform awareness of what it is trying to promote in its eastern neighbourhood under the aegis of 'shared values', 'collective norms' and 'joint ownership'. Secondly, empirically, the EU seems to favour a 'top-down' governance approach (based on rule/norm transfer and conditionality) in its relations with outsiders, which is clearly at odds with a voluntary idea of 'partnership', and explicitly limits the input of 'the other' in the process of reform.[51]

See also

[edit]- Association Trio

- Community for Democracy and Rights of Nations

- Community of Democratic Choice

- Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area

- Eastern European Group

- Euromaidan

- Euronest Parliamentary Assembly

- Eurosphere

- Eurasian Economic Union

- European integration

- Eurovoc

- EU Strategy for the South Caucasus

- Greater Europe

- INOGATE

- Politics of Europe

- Potential enlargement of the European Union

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Eastern Partnership - EEAS - European External Action Service - European Commission". EEAS - European External Action Service. Retrieved 10 December 2018. Content is copied from this source, which is (c) European Union, 1995-2018. Reuse is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Poland takes on Russia with 'Eastern Partnership' proposal, The Daily Telegraph, 2008-05-25

- ^ EU pact challenges Russian influence in the east, Guardian.co.uk, 2009-05-07

- ^ "Eastern Partnership implementation well on track". Europa.eu. 8 December 2009.

- ^ "EEAS - European External Action Service - European Commission". EEAS - European External Action Service. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- ^ EU might get new Eastern Partnership, Barents Observer, 2008-05-22

- ^ "Poland and Sweden to pitch 'Eastern Partnership' idea", EUObserver, 2008-05-22

- ^ "'Eastern Partnership' could lead to enlargement, Poland says". EU Observer. 27 May 2008.

- ^ Poland, Sweden defend 'Eastern initiative' Archived 27 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine, EurActive.com, 2008-05-26

- ^ "'Eastern Partnership' could lead to enlargement, Poland says", EU Observer, 2008-05-27

- ^ "'EU reaches out to troubled East", BBC News, 2009-05-07

- ^ a b EU assigns funds and staff to 'Eastern Partnership', EU Observer, 2009-03-20

- ^ Belarus quits EU's Eastern Partnership initiative Archived 2 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Eur Activ, 2011-10-30

- ^ Belarus still Participating in "Eastern Partnership," FM Archived 15 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine, [1], 2011-11-03

- ^ https://en.armradio.am/2021/06/28/belarus-suspends-participation-in-eastern-partnership-initiative/ Belarus suspends participation in Eastern Partnership initiative

- ^ Karina SHYROKYKH (December 2017). "Effects and side effects of European Union assistance on the former Soviet republics". Democratization. 24 (4): 651–669. doi:10.1080/13510347.2016.1204539. S2CID 148150487.

- ^ Values to form core of EU 'Eastern Partnership', EU Observer, 2009-03-18

- ^ Karina SHYROKYKH (June 2021). "Human rights sanctions and the role of black knights: Evidence from the EU's post-Soviet neighbours". Journal of European Integration. 44 (3): 429–449. doi:10.1080/07036337.2021.1908278. S2CID 237828279.

- ^ Balkans model to underpin EU's 'Eastern Partnership', EU Observer, 2008-09-18

- ^ "EAP Generic Factsheet" (PDF). Eeas.europa.eu. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- ^ "Vademecum on Financing in the Frame of the Eastern Partnership" (PDF). Eeas.europa.eu. Retrieved 4 January 2011.

- ^ "Trust fund". Eib.org. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- ^ "EPTATF Internships". Eib.org. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- ^ Mejlumyan, Ani (15 July 2021). "Armenia gets boost from EU | Eurasianet". DiasporArm.org. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- ^ "The future of the Trio Plus Strategy 2030: building a future of Eastern Partnership" (PDF).

- ^ "European Lawmakers Call For Eastern Partners' Greater Integration". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 20 June 2020.

- ^ "Офіційне інтернет-представництво Президента України". Офіційне інтернет-представництво Президента України. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- ^ Karina SHYROKYKH (June 2018). "The Evolution of the Foreign Policy of Ukraine: External Actors and Domestic Factors". Europe-Asia Studies. 70 (5): 832–850. doi:10.1080/09668136.2018.1479734. S2CID 158408883.

- ^ "Joint Declaration of the Prague Eastern Partnership Summit" (PDF). Consilium.europa.eu. Prague. 7 May 2009. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- ^ a b EU expanding its 'sphere of influence,' Russia says, EU Observer, 2009-03-21

- ^ "Sikorski: umowa o małym ruchu granicznym od 1 lipca". Gazeta Wyborcza. 17 June 2009. Retrieved 17 June 2009.

- ^ "Playing East against West: The success of the Eastern Partnership depends on Ukraine". The Economist. 23 November 2013.

- ^ Korosteleva, E.A., "The Limits of the EU Governance: Belarus ' Response to the European Neighbourhood Policy", Contemporary Politics, Vol. 15(2), June 2009, pp. 229–45

- ^ "Lavrov: Russia could join EU Eastern Partnership". Hurriyet. 25 November 2009.

- ^ "Польша: Увидев процветающую в ЕС Украину, Россия сама попросит об экономической интеграции с нами". Regnum.ru. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- ^ Ritter, Karl; Casert, Raf (21 May 2015). "EU seeks to keep partnership with ex-Soviet nations on track". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 22 May 2015. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ^ Ritter, Karl; Casert, Raf (22 May 2015). "EU embrace of eastern partners turns lukewarm". Associated Press.

- ^ "Eastern Partnership – Civil Society Forum". European Commission website. Archived from the original on 12 July 2009.

- ^ "Resolution of the 1st EaP CSF Civil Society Summit". eap-csf.eu.

- ^ "Eastern Partnership Index". eap-csf.eu.

- ^ "Statement: EaPCSF condemns arrests of internationally respected civil society leaders in Azerbaijan". Eap-csf.eu. Archived from the original on 10 July 2015.

- ^ "Press release - Brussels, 7 May 2009 Joint Declaration of the Prague Eastern Partnership Summit, Prague". European Commission. 7 May 2009. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ "Press release - José Manuel Durão Barroso President of the European Commission Statement by President Barroso following the Eastern Partnership Summit Eastern Partnership Summit Warsaw". European Commission. 30 September 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ "European Commission - PRESS RELEASES - Press release - Third Eastern Partnership summit, Vilnius 28-29 November 2013". Europa.eu. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- ^ "Joint Declaration of the Eastern Partnership Summit" (PDF). Consilium.europa.eu. Vilnius. November 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- ^ "Eastern Partnership summit, Riga, 21-22/05/2015 - Consilium". Consilium.europa.eu. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- ^ "Eastern Partnership summit, 24/11/2017 - Consilium". Consilium.europa.eu. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- ^ "Eastern Partnership: a renewed agenda for recovery, resilience and reform underpinned by an Economic and Investment plan". europa.eu. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ "Moldova most EU-friendly Eastern country, survey reveals". Euractive.com. 14 June 2010. Archived from the original on 22 January 2013. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "Europeanizing or Securitizing the 'outsiders'? Assessing the EU's partnership-building approach with Eastern Europe". Esrcsocietytoday.ac.uk. 10 October 2009. Archived from the original on 10 October 2009. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

External links

[edit]- Eastern Partnership

- European Neighbourhood Policy and Enlargement Negotiations - Eastern Partnership

- Eastern Partnership on Twitter

- EU Neighbourhood Info Centre

- EU Neighbourhood Library

- European External Action Service: Eastern Partnership (europa.eu)

- Eastbook.eu – Portal on Eastern Partnership: Eastbook.eu Archived 25 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Eastern Partnership Civil Society Forum: [2] (eap-csf.eu)

- Eastern Partnership Community: Eastern Partnership Community (easternpartnership.org)

- Europeanizing or Securitizing the 'outsiders'? Assessing the EU's partnership-building approach with Eastern Europe Archived 20 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- The Eastern Partnership – an ambitious new chapter in the EU's relations with its Eastern neighbours (europa.eu, 3 December 2008)

- European Council – Conclusions (Declaration in annex II) (europa.eu, 19–20 March 2009)

- Eastern Partnership Summit Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine (eu2009.cz, 7 May 2009)

- Joint Declaration of the Eastern Partnership Summit (europa.eu, 7 May 2009)

- Conference Eastern Partnership: Towards Civil Society Forum[permanent dead link]

- Eastern Partnership: The Opening Report – submitted by the Polish Institute of International Affairs (www.pism.pl, April 2009)

- Marcin Łapczyński: The European Union's Eastern Partnership: Chances and Perspectives – submitted by the Caucasian Review of International Affairs (www.cria-online.org, Spring 2009)

- Schäffer, Sebastian; Tolksdorf, Dominik (April 2009). "The Eastern Partnership – 'ENP plus' for Europe's Eastern neighbors". Centrum für angewandte Politikforschung.

- Sebastian Schäffer und Dominik Tolksdorf: „The EU member states and the Eastern Neighbourhood – From composite to consistent EU foreign policy?", CAP Policy Analysis, August 2009.

- "Polish-Swedish Proposal: Eastern Partnership", June 2008.

- Belarus Engages Ukraine, Moldova, Improves Ties With EU And US – Foreign Policy Digest Archived 21 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Central And Eastern European Dimension Of Belarusian Diplomacy – Belarus Foreign Policy Digest Archived 3 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

[edit]Academic policy papers

[edit]- Moldova's Values Survey: Widening a European Dialogue in Moldova, Global Europe Centre, University of Kent, January 2014

- Visegrad 4 the Eastern Partnership: Towards the Vilnius Summit, Research Center of the Slovak Foreign Policy Association, Bratislava, October 2013

- Belarus and the Eastern Partnership: a National Values SurveyGlobal Europe Centre, University of Kent, October 2013

- Building a Stronger Eastern Partnership: Towards an EaP 2.0, Global Europe Centre, University of Kent, September 2013

- The EEAS and the Eastern Partnership: Let the blame game stop, Centre for European Policy Studies, September 2012

- German Foreign Policy and Eastern Partnership: Position Paper of the Eastern Partnership Task Force, German Council on Foreign Relations, February 2012 Archived 16 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

Books

[edit]- Korosteleva, E.A., Natorski, M. and Simao, L.(Eds.), (2014), EU Policies in the Eastern Neighbourhood: the practices perspective, London: Routledge, ISBN 0415720575

- Korosteleva, E.A. (2012),The European Union and its Eastern Neighbours: Towards a more ambitious partnership? London: BASEES/Routledge Series on Russian and East European Studies, ISBN 0-415-61261-6

- Korosteleva E.A, (Ed.), (2011), Vostochnoe Partnerstvo: problemy i perspektivy [Eastern Partnership: problems and perspectives], Minsk: Belarusian State University, ISBN 978-985-491-088-8

- Korosteleva, E.A. (Ed.) (2011), Eastern Partnership: A New Opportunity for the Neighbours?, London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-67607-X

- Whitman, R., & Wolff, S., (Ed.), (2010), The European Neighbourhood Policy in perspective: context, implementation and impact, Palgrave:London, ISBN 023020385X

Journal articles

[edit]- Ambassador Gert ANTSU: ”We just cannot afford to lose interest in Eastern neighbors” — Interview of Ambassador Gert ANTSU for Caucasian Journal, 19.01.2022.

- Ambassador Gert ANTSU: ”At times reforms sound like a tired buzzword that has lost its luster” — Interview of Ambassador Gert ANTSU for Caucasian Journal, 18.07.2021.

- Korosteleva, E.A, 'Change or Continuity: Is the Eastern Partnership an Adequate Tool for the European Neighbourhood', International Relations, 25(2) June 2011: 243–62

- Korosteleva, E.A, 'Change or Continuity: Is the Eastern Partnership an Adequate Tool for the European Neighbourhood', International Relations, 25(2) June 2011: 243–62

- Whitman, R., European Union's relations with the Wider Europe' Journal of Common Market Studies Annual Review of the European Union in 2010, 49, (2011). pp. 187–208.

- Korosteleva, E.A, 'Eastern Partnership: a New Opportunity for the Neighbours?', Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics, Special Issue, 27(1) 2011: 1–21

- Korosteleva, E.A, 'Moldova's European Choice: Between Two Stools', Europe-Asia Studies, 61(8) 2010: 1267–89

- Wolfgang Tiede and Jakob Schirmer: "The EU's Eastern Partnership – Objectives and Legal Basis", in: "The European Legal Forum" (EuLF) 3/2009, pp. 168–174.

- Korosteleva, E.A, 'The Limits of the EU Governance: Belarus' Response to the European Neighbourhood Policy', Contemporary Politics, 15 (2) 2009: 229–45

- Bosse, G., & Korosteleva, E.A, 'Changing Belarus? The Limits of EU Governance in Eastern Europe', Cooperation and Conflict, 44 (2) 2009: 143–165

- Yefremenko, D. Life after Vilnius. A new geopolitical configuration for Ukraine. // Russia in global affairs. - Vol. 11, No. 3 - July – September 2013.

- Treaties entered into by the European Union

- Foreign relations of Armenia

- Foreign relations of Azerbaijan

- Foreign relations of Ukraine

- Foreign relations of Belarus

- Armenia–European Union relations

- Georgia (country)–European Union relations

- Moldova–European Union relations

- Ukraine–European Union relations

- Eastern Europe

- European integration

- International organizations based in Europe