History of Nintendo

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2022) |

The history of Nintendo, a Japan-based international video game company, starts in 1889 when Fusajiro Yamauchi founded "Yamauchi Nintendo", a producer of hanafuda playing cards. Since its founding, the company has been based in Kyoto.[1] Sekiryo Kaneda was Nintendo's president from 1929 to 1949. His successor, Hiroshi Yamauchi, had the company producing toys like the Ultra Hand, and operating love hotels. In the 1970s and '80s, Nintendo made arcade games, the Color TV-Game series of home game consoles, and the Game & Watch series of handheld electronic games.

Shigeru Miyamoto designed the arcade game Donkey Kong (1981): Nintendo's first international hit video game, and the origin of the company's mascot, Mario. After the video game crash of 1983, Nintendo filled a market gap in the West by releasing their Japanese Famicom home console (1983) as the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) in the U.S. in 1985. Miyamoto and Takashi Tezuka's innovative NES titles, Super Mario Bros. (1985) and The Legend of Zelda (1986), were highly influential to video games.

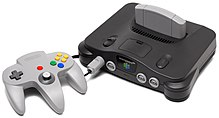

The Game Boy handheld console (1989) and the Super Nintendo Entertainment System home console (1990) were successful, while Nintendo had an intense business rivalry with console maker Sega. Nintendo owned the Seattle Mariners, an American baseball team, from 1992 to 2016. The Virtual Boy (1995), a portable console with stereoscopic 3D graphics, was a critical and financial failure. With the Nintendo 64 (1996) and its innovative launch title Super Mario 64, the company began making games with fully-3D computer graphics. The Pokémon media franchise, partially owned by Nintendo, has been a worldwide hit since the 1990s.

The Game Boy Advance (2001) was another success. The GameCube home console (2001), while popular with core Nintendo fans, had weak sales compared to Sony and Microsoft's competing consoles. In 2002, Hiroshi Yamauchi was succeeded by Satoru Iwata, who oversaw the release of the Nintendo DS handheld (2004) with a touchscreen, and the Wii home console (2006) with a motion controller; both were extraordinarily successful. Nintendo, now targeting a wide audience including casual gamers and previously non-gamers, essentially stopped competing with Sony and Microsoft, who targeted devoted gamers. Wii Sports (2006) remains Nintendo's best-selling game.

The Nintendo 3DS handheld (2011) successfully retried stereoscopic 3D. The Wii U home console (2012) sold poorly, putting Nintendo's future as a manufacturer in doubt, and influencing Iwata to bring the company into mobile gaming. Iwata also led development of the successful Nintendo Switch (2017), a home/handheld hybrid console, before his death in 2015. He was succeeded by Tatsumi Kimishima until 2018, followed by current president Shuntaro Furukawa.

1889–1949: Hanafuda cards

[edit]

Nintendo was founded as Yamauchi Nintendo (山内任天堂) by Fusajiro Yamauchi on September 23, 1889.[2][3] though it was originally named Nintendo Koppai. Based in Kyoto, Japan, the business produced and marketed hanafuda, a type of Japanese playing card. The name "Nintendo" is commonly assumed to mean "leave luck to heaven", but there are no historical records to validate this.[4] Hanafuda cards were an alternative to Western-style playing cards which were banned in Japan at the time. Nintendo's cards gained popularity, so Yamauchi hired assistants to mass-produce them.

Fusajiro Yamauchi did not have a son to take over the family business. Following the common Japanese tradition of mukoyōshi, he adopted his son-in-law, Sekiryo Kaneda, who then legally took his wife's last name of Yamauchi. In 1929, Fusajiro Yamauchi retired and allowed Kaneda to take over as president. In 1933, Sekiryo Kaneda established a joint venture with another company and renamed it Yamauchi Nintendo & Co.

Nintendo's headquarters were almost destroyed in 1945 during World War II, when the United States military was preparing to use their newly-invented nuclear bomb on a Japanese city; in June 1945, Kyoto was the top city considered for an attack, but U.S. Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson removed it as a potential target due to his appreciation of the city.[5]

In 1947, Sekiryo established a distribution company, Marufuku Co., Ltd.,[6] to distribute the hanafuda and several other types of cards produced by Nintendo. Sekiryo Kaneda also had only daughters, so again his son-in-law (Shikanojo Inaba, renamed Shikanojo Yamauchi) was adopted into the family. Yamauchi later abandoned his family and did not become company president. Subsequently, his son Hiroshi Yamauchi was brought up by his grandparents and he later took over the company instead of his father.

1949–1966: Disney partnership and public listing

[edit]

In 1949, Hiroshi Yamauchi attended Waseda University in Tokyo. However, after his grandfather suffered a debilitating stroke, he left to take office as the president of Nintendo.[7] In 1950, he renamed Marufuku Co. Ltd. to Nintendo Karuta (任天堂かるた), and in 1951 to Nintendo Karuta (任天堂骨牌) (writing "karuta" as "骨牌" rather than "かるた").[8][9][10] In 1953, Nintendo became the first company in Japan to produce playing cards from plastic.[11]

In 1956, Yamauchi visited the U.S., to engage in talks with the United States Playing Card Company (USPCC), the dominant playing card manufacturer in the United States, based in Cincinnati. He was shocked to find that the world's biggest company in his business was relegated to using a small office. This was a turning point for Yamauchi, who then realized the limitations of the playing card business.[citation needed]

In 1958, Nintendo made a deal with Disney to allow the use of Disney's characters on Nintendo's playing cards.[9] Previously, Western playing cards were regarded as something similar to hanafuda and mahjong: a device for gambling. By tying playing cards to Disney and selling books explaining the different games playable with the cards, Nintendo could sell the product to Japanese households. The tie-in was a success and the company sold at least 600,000 card packs in one year. Due to this success, in 1962, Yamauchi took Nintendo public, listing the company in Osaka Stock Exchange Second division.[10]

In 1963, Nintendo Playing Card Co., Ltd. was renamed to Nintendo by Yamauchi.[10] Nintendo started to begin experimenting in other areas of business using the newly injected capital. This included establishing a food company in partnership with two other firms with a product line featuring instant rice (similar to instant noodles),[12] a vacuum cleaner, and Chiritory. All these ventures eventually failed, except toymaking, based on some earlier experience from selling playing cards.[13] In 1964, while Japan was experiencing an economic boom due to the Tokyo Olympics, the playing card business reached saturation. Japanese households stopped buying playing cards, and the price of Nintendo stock fell from 900 yen to 60 yen.[14]

In 1965, Nintendo hired Gunpei Yokoi as a Maintenance Engineer for the assembly line. However, Yokoi soon became famous for much more than his ability to repair conveyor belts.[15]

1966–1972: Toy company and new ventures

[edit]During the 1960s, Nintendo struggled to survive in the Japanese toy industry, which was still small at this point, and already dominated by already well-established companies such as Bandai and Tomy. Because of the generally short product life cycle of toys, the company took the approach of introducing new products at a quicker rate, marking the start of a major new era for Nintendo.

In 1966, Yamauchi, upon visiting one of the company's hanafuda factories, noticed an extending arm-shaped toy, which had been made by one of its maintenance engineers, Gunpei Yokoi, for his own enjoyment. Yamauchi ordered Yokoi to develop it as a proper product for the Christmas rush. Released as the Ultra Hand, it became one of Nintendo's earliest toy blockbusters, selling over hundreds of thousands units. Seeing that Yokoi had potential, Yamauchi pulled him off assembly line work. Yokoi was soon moved from maintenance duty to product development.

Due to his electrical engineering background, it soon became apparent that Yokoi was quite adept at developing electronic toys. These devices had a much higher novelty value than traditional toys, allowing Nintendo to charge a higher price margin for each product. Yokoi went on to develop many other toys, including the Ten Billion Barrel puzzle, a baseball throwing machine called the Ultra Machine, and a Love Tester.

Nintendo released the first solar-powered light gun, the Nintendo Beam Gun,[16] in 1970; this was the first commercially available light-gun for home use, produced in partnership with Sharp.[17]

In 1972, Nintendo released the Ele-Conga, one of the first programmable drum machines. It plays pre-programmed rhythms from disc-shaped punch cards, which can be altered or programmed by the user, to play different patterns.[18]

1972–1983: Arcade, Color TV-Game, and Game & Watch era

[edit]Released in 1972, the first commercially available video game console, the Magnavox Odyssey, has a light gun accessory, the Shooting Gallery.[19] This was the first involvement of Nintendo in video games. According to Martin Picard in the International Journal of Computer Game Research: "in 1971, Nintendo had—even before the marketing of the first home console in the United States—an alliance with the American pioneer Magnavox to develop and produce optoelectronic guns for the Odyssey (released in 1972), since it was similar to what Nintendo was able to offer in the Japanese toy market in 1970s".[20]

In 1973, its focus shifted to family-friendly arcades with the Laser Clay Shooting System,[21] using the same light gun technology used in Nintendo's Kousenjuu series of toys, and set up in abandoned bowling alleys. Gaining some success, Nintendo developed several more light gun machines for the emerging arcade scene. While the Laser Clay Shooting System ranges had to be shut down following excessive costs, Nintendo had founded a new market.

Nintendo also entered the video game market. Its first steps were to acquire the rights to distribute the Magnavox Odyssey in Japan in 1974 and to release its first video arcade game, EVR Race,[22] in 1975. In 1977, Nintendo released the Color TV-Game 6 and Color TV-Game 15, two consoles jointly developed with Mitsubishi Electric. The numbers in the console names indicate the number of games included in each.[10]

In the early 1980s, Nintendo's video game division was led by Yokoi to create some of its most famous arcade games. The massively popular Donkey Kong was designed by Shigeru Miyamoto and released in arcades in 1981. Home releases soon followed, made by Coleco for the Atari 2600, Intellivision, and ColecoVision video game systems. Some of Nintendo's other arcade games were ported to home consoles by third parties, including Donkey Kong Jr., Sky Skipper, Mario Bros., and Donkey Kong 3. Nintendo started to focus on the home game market. It stopped manufacturing and releasing arcade games in Japan in late 1985,[23][24] and withdrew its membership from the Japan Amusement Machinery Manufacturers Association (JAMMA) on February 28, 1989.[25]

The release of Donkey Kong caused Universal Studios, Inc. to take legal action and sue Nintendo for copyright infringement on their character King Kong, which was actually in the public domain. The court sided with Nintendo in Universal City Studios, Inc. v. Nintendo Co., Ltd.. Nintendo thanked their lawyer, John Kirby, by giving him a $30,000 boat called the Donkey Kong, along with "exclusive worldwide rights to use the name for sailboats," and named the character Kirby after him.[26]

In addition to the arcade game activity, Nintendo was testing the consumer handheld video game market with the Game & Watch. It is a line of handheld electronic games produced by Nintendo from 1980 to 1991. Created by game designer Gunpei Yokoi, each Game & Watch features a single game to be played on an LCD screen in addition to a clock or an alarm. It is the earliest Nintendo product to garner major success, with 43.4 million units sold worldwide.

1983–1989: Famicom and Nintendo Entertainment System era

[edit]

In 1982, Nintendo developed a prototype system called the Advanced Video System (AVS). Its accessories include controllers, a tape drive, a joystick, and a lightgun. The system can be used as a simple home computer. It was never released and is on display at the Nintendo World Store in New York.[27][28][29] In July 1983, Nintendo released the Family Computer console in Japan, as its first attempt at a cartridge-based video game console. More than 500,000 units were sold within two months at around $100 each. After a few months of favorable sales, Nintendo received complaints that some Famicom consoles would freeze on certain games. The fault was found in a malfunctioning chip and Nintendo decided to recall all Famicom units that were currently on store shelves, at a cost of approximately $500,000.[citation needed]

During this period, Nintendo redesigned the Famicom as the Nintendo Entertainment System for its launch in the United States. Since the company had very little experience with the US market, it had previously attempted to contract with Atari for the system's distribution in 1983. However, a controversy involving Coleco and Donkey Kong soured the relationship between the two during the negotiations, and Atari refused to back Nintendo's console.

In 1983–1985, a large scale recession in video game sales hit the market which amounted to a 97% decrease primarily in the North American area. Known as the video game crash of 1983, the recession was caused by many factors, including: the amount of competing home consoles, the amount of poorly-received games on consoles, competition to consoles from home computers, inflation, and console manufacturers losing the ability to control which games could legally be sold for their consoles. The crash greatly damaged the vast majority of the American gaming market, and console manufactures like Atari and Coleco were unable to find success in selling consoles. Within a few years, the majority of video game sales were within Japan.

Nintendo decided that, to have their console be successful in North America, they were determined not to make the same mistakes there that Atari and other manufacturers had. Nintendo decided to have strict oversight over what games would be legally allowed to be published for their console, leading to the "Seal of Quality" that was put on every game published for a Nintendo console from that point on.

From 1984 until 2004, Nintendo's employees were divided into four research & development (R&D) divisions; Research & Development 4, as it was named at its founding, was created in 1984 as the team behind most internal game development, led by Shigeru Miyamoto. It was renamed Entertainment Analysis & Development (EAD) by 2004.[30][31]

In 1985, Nintendo announced the release of the Famicom (Family Computer) worldwide with a different design under the name the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES). It used a creative tactic to counter the bad press on video games, and released the NES with R.O.B. units that connect to the games. To ensure the localization of the highest-quality games by third-party developers, Nintendo of America limited third-party developers to five game releases in a single year. Konami, the first third-party company allowed to make Famicom games, later circumvented this rule by creating a spinoff company, Ultra Games, to release additional games per year. Other manufacturers soon employed the same tactic. Also in 1985, Super Mario Bros. was released for the Famicom in Japan and became a large success, along with it also releasing in America which caused the video game industry to be revived and became the most successful and popular Nintendo and Mario game until Mario Kart 8 released in 2014.[citation needed]

Nintendo test marketed the Nintendo Entertainment System in the New York area on October 18, 1985. They expanded the test to Los Angeles in February 1986, followed by tests in Chicago and San Francisco. They would go national by the end of 1986, along with 15 games, sold separately. In the U.S. and Canada, it widely outsold its competitors. Also in 1986, Metroid and The Legend of Zelda were released to much critical acclaim.

In 1988, Nintendo of America unveiled Nintendo Power, a monthly news and strategy magazine from Nintendo that served to advertise new games. The first issue is July/August, which spotlights the NES game Super Mario Bros. 2 (Super Mario USA in Japan). Nintendo Power has since ceased publication with its December 2012 edition.[32]

1989–1996: Game Boy, Super Nintendo Entertainment System, and Virtual Boy era

[edit]In 1989, Nintendo (which had much success from the Game & Watch) released the Game Boy (also created by Gunpei Yokoi), along with the accompanying game Tetris. Due to the price, the game, and its durability (unlike the static and screen rot of the prior Microvision from Milton Bradley Company), the Game Boy line eventually amassed sales of 118 million units.[33] Super Mario Land was released with the system, and 14 million copies were sold worldwide. Also in 1989, Nintendo announced a successor to the Famicom, the Super Famicom.[34]

The last major first-party game for the NES was Super Mario Bros. 3, which was released in early 1990 in North America, with more than 18 million units sold.[35] It was followed by a licensed television adaption named The Super Mario Bros. Super Show!, which was released by DIC Entertainment and Viacom Enterprises in that year to capitalize on the game's immense popularity.

The Super Famicom was released in Japan on November 21, 1990. The launch was widely successful, and the Super Famicom was sold out across Japan within three days, with 1.6 million units sold by June 1991.[36] In August 1991, the Super Famicom was launched in the U.S. under the name "Super Nintendo Entertainment System" (SNES), followed by Europe in 1992.[37]

Like the NES, the Super Nintendo Entertainment System has high technical specifications for its era. The SNES controller had also improved over that of the NES, as it now had rounded edges and four new buttons, a standard which is evident on many modern controllers today.

Nintendo had begun development on a CD-ROM attachment for the SNES/Super Famicom. Its first partner in this project was Sony, which had provided the SNES with its SPC sound chip. Development on the Nintendo PlayStation CD-ROM add-on and SNES/SFC standalone hybrid console began. However, at the last minute Nintendo decided to pull out of the partnership and instead go with Philips, and while no CD-ROM add-on was produced, several Nintendo properties (namely The Legend of Zelda) appeared on the Philips CD-i media console. Upon learning this, Sony decided to continue developing the technology they had into the PlayStation. The exact reason Nintendo left its partnership with Sony has been the subject of speculation over the years, but the most common theory is that Sony either wanted too much of the profits for the machine or the rights to the CD-ROM attachment itself.

In Japan, the Super Famicom easily took control of the gaming market. In the U.S., due to a late start and an aggressive marketing campaign by Sega (based around by Sega's new mascot, Sonic the Hedgehog, their answer to Mario), Nintendo's market share plunged from 90 to 95% with the NES to a low of approximately 35% against the Sega Genesis. Across several years, the SNES in North America eventually overtook the Genesis, due to franchise games such as Super Mario World, The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past, Street Fighter II, and the Final Fantasy series. Total worldwide sales of the SNES reached 49.10 million units,[33] eclipsing the estimated 40 million unit sales of the Genesis.[38]

As the SNES battled the Sega Genesis, Nintendo had problems caused by its own aggressive marketing behavior. In 1991, Nintendo agreed to a settlement regarding price-fixing allegations brought by the Federal Trade Commission and attorneys general in New York and Maryland. Nintendo had been accused of threatening to cut off shipments of the NES to retailers who discounted the price of the system. The estimated cost of the settlement was just under $30 million.[39]

On July 31, 1992, Nintendo of America announced it would no longer manufacture arcade equipment.[40][41]

In 1992, Gunpei Yokoi and the rest of R&D 1 began planning on a new stereoscopic 3D console which became the Virtual Boy. Hiroshi Yamauchi also bought majority shares of the Seattle Mariners in 1992.[42] By May 1993, Nintendo had reportedly become one of the top ten leading companies in the world.[43]

In 1993, Nintendo announced plans to develop a new 64-bit console codenamed Project Reality, capable of rendering fully 3D environments and characters. In 1994, Nintendo also claimed that Project Reality would be renamed Ultra 64 in the US. The Ultra 64 moniker was unveiled in arcades on the Nintendo branded fighting game Killer Instinct and the racing game Cruis'n USA. Killer Instinct was later released on the SNES. Soon after, Nintendo realized Konami owned the rights to the "Ultra" name. Specifically, only Konami had rights to release games for the new system with names like Ultra Football or Ultra Tennis. Therefore, in 1995 Nintendo changed the final name of the system to Nintendo 64, and announced that it would be released in 1996. The system and several games were previewed, including Super Mario 64, to the media and public. Also in 1995, Nintendo purchased part of Rare.

In 1994, after many years of Nintendo's products being distributed in Australia by Mattel since the NES in 1985, Nintendo opened its Australian headquarters and its first managing directors were Graham Kerry, who moved along from Mattel Australia as managing director and Susumu Tanaka of Nintendo UK Ltd.

In 1995, Nintendo released the Virtual Boy in Japan. The console sold poorly, with a record of less than 500,000 units but Nintendo still said they had hope for it and continued to release several other games and attempted a release in the US, which was another disaster.

Also in 1995, Nintendo had new competition when Sega introduced their 32-bit Saturn, while newcomer Sony introduced the 32-bit PlayStation. Sony's fierce marketing campaigns ensued, and it started to cut into Nintendo and Sega's market share.

1996–2001: Nintendo 64 and Game Boy Color era

[edit]

On June 23, 1996, the Nintendo 64 was released in Japan, with more than 500,000 units sold on the first day.[21] On September 29, 1996, the Nintendo 64 was released in North America, selling out the initial shipment of 350,000.[21] Nintendo's extremely competitive climate was pushed by many third-party companies immediately developing and releasing many of their leading games for Nintendo's competitors. Many of those third-party companies cited cheaper development and manufacturing costs for the CD format, versus the cartridge format.

Nintendo followed with the release of the Game Boy Pocket, a smaller version of the original Game Boy, designed by Gunpei Yokoi as his final product for the company. A week after the release of the Game Boy Pocket, he resigned from his position at Nintendo. He then helped in the creation of the competing handheld WonderSwan.

In 1996, Pocket Monsters (known internationally as "Pokémon") was released for the Game Boy in Japan to a huge following. The Pokémon franchise, created by Satoshi Tajiri, was proving so popular in America, Europe, and Japan, that for a brief time, Nintendo took back their place as the supreme power in the games industry.[citation needed]

In 1997, Gunpei Yokoi died in a car accident at the age of 56.[15]

Also in 1997, the European Economic Community forced Nintendo to drastically rework its third-party licensing contracts, ruling that Nintendo could no longer limit the number of games a license could release, require games to undergo prior approval, or require third-party games to be exclusively manufactured by Nintendo.[44]

On October 13, 1998, the Game Boy Color was released in Japan, with releases in North America and Europe a month later.

The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, the first Zelda game to use a fully-3D graphics engine, released for the Nintendo 64 in 1998. It popularized both the "context-sensitive button" game mechanic, which allows a controller's button to have multiple different uses in a game, depending on the player's location in the game world; and "camera lock-on", which lets the player force the game's camera to only rotate around one point in 3D space—in this case a specific enemy—to make fighting the enemy easier.[45][46][47] 1Up.com wrote in 2012 that these additions made Ocarina of Time feel "intuitive" as opposed to "the bulk of 3D action adventures in the mid-to-late [nineties, which] played like hell". The game was unimamously lauded by critics.[47] As of 2025, Guinness World Records labels Ocarina of Time the "most critically acclaimed video game ever", as its average review score from critics is a 99 out of 100 on Metacritic.[48]

In 1998, as Nintendo was developing its next home console, codenamed Dolphin at the time, the company worked with American game producer Jeff Spangenburg (who previously worked at Acclaim Entertainment, then-publisher of the Turok game series) to found Retro Studios, a game development studio based in Austin, Texas. Spangenberg was fired from Acclaim earlier that year, and then secured a deal with Nintendo of America to develop for the Dolphin; Nintendo funded Retro's 40,000-square-foot studio. Within a few years, the studio had about 150 employees.[49]

In December 1998, Nintendo sued the owner of the "zelda.com" domain name, which linked to pornographic images.[50] In December 1999, illusionist Uri Geller sued Nintendo for £60 million over his likeness allegedly being represented in the Pokémon species Alakazam.[51][52] The lawsuit was dropped in 2003, and Geller sued multiple times after; in 2020, he apologized for the legal battle.[53]

In 1999, Nintendo released the 64DD, a disk drive peripheral that allowed the Nintendo 64 to play disk-based games. The company advertised the device in international gaming magazines for years prior, essentially saying it would "change the way we play games". However, the 64DD was only sold in Japan, and only seven games were made for it. The peripheral was mainly sold only through a website called Randnet, as a bundle with all seven games.[54]

The Dolphin was officially announced as Nintendo's next home console at E3 1999; Nintendo of America president Howard Lincoln declared the system would "equal or exceed anything our friends at Sony can come up with for PlayStation 2" (PS2).[55] At Nintendo's "SpaceWorld 2000" trade show the next year, more details were given on the Dolphin, revealed to be named the "GameCube".[56][57]

The GameCube had a more ergonomic controller than previous Nintendo consoles, and included a handle for easy carriage. Its games were released in disk format, meaning the console, in theory, had enough power to attract third-party developers back to the system after the relative weakness of the Nintendo 64. However, the mini-disc format was used, as to prevent piracy and not pay fees to the DVD Forum consortium, who made DVD technologies such as game disks; this meant a GameCube disk could only store 1.6 gigabytes of data, which was once again underpowered compared to Nintendo's competitors.[55][58] While developing the system, Nintendo built an peripheral for it which included an LCD screen, that could function as a second display for games—aside from the monitor connected to the console itself—and display stereoscopic 3D graphics, similar to the Virtual Boy. Nintendo's developers were able to run the game Luigi's Mansion (which released for the GameCube in 2001[55]) on the peripheral, but mass-producing it would have been too expensive for the company.[55]

In March 2000, Nintendo made an $80 million USD settlement with the Attorney General of New York, over hand injuries sustained by children while rotating the Nintendo 64 controller's joystick in five different mini-games within Mario Party (1998). The company issued game gloves to prevent future injuries.[59] In June 2000, Nintendo announced that they had gotten Apollo Ltd., a major Hong Kong company who had produced pirated versions of Nintendo games, shut down by Hong Kong law enforcement.[60][61]

2001–2004: Game Boy Advance and GameCube era

[edit]

Nintendo released the Game Boy Advance (GBA) handheld console in Japan on March 21, 2001, followed by North America and Europe in June.[56][62] The system had a much larger screen than previous versions of the Game Boy, and its screen could display more colors than the Game Boy Color. The GBA had backwards compatibility with Game Boy and Game Boy Color cartridges, and much like the unreleased accessory for the Dolphin, it could connect to the GameCube using a "Link Cable" and be used as a second display for compatible GameCube games.[57] In North America, the GBA was highly successful at launch, becoming Nintendo's fast-selling system at the time, with 500,000 units sold in around a month.[62]

In the early 2000s, Sega stopped making game consoles after the financial failure of their Dreamcast home console, which released in 1998.[55][63] Becoming solely a game developer and publisher, Sega began releasing their developers' games on Nintendo consoles; notably, the first Sonic the Hedgehog game on a Nintendo system was Sonic Advance for the GBA in 2002.[64] Sony became Nintendo's main rival in the console field,[55] but both companies now competed against technology company Microsoft, who released the Xbox home console in 2001.[65]

The GameCube was released in September 14, 2001, in Japan; North America in November 2001; and Europe in May 2002.[58] The system had a strong launch—Nintendo said it was stronger than those of the PS2 and Xbox—but sales in succeeding months were lower than expected.[66][67][55] This was partially due to the system's small early library that included Luigi's Mansion, which was seen as an underwhelming launch title. The GameCube also lacked a built-in DVD player, while the PS2 included one; the Panasonic Q edition of the GameCube, which could play DVDs, was only released in Japan.[55][58]

In January 2002, Minoru Arakawa resigned as president of Nintendo of America, and Nintendo named Tatsumi Kimishima as his successor.[68] In May 2002, Hiroshi Yamauchi stepped down as Nintendo's corporate president, and named Satoru Iwata as his successor.[69]

Despite the GameCube's technological improvements, third parties generally still kept away from the system. Nintendo was late in giving development kits to third-party developers in the lead-up to the system's launch.[55] Gavin Lane later wrote for Nintendo Life that the console was also hurt by Nintendo continuing to target a demographic of younger players, despite having an older audience of people who owned previous Nintendo consoles, while Sony "expertly co-opted anxious teenagers desperate to distance themselves from childish things" with the PS2.[55][70] The cartoon-like aesthetic of the GameCube title The Legend of Zelda: Wind Waker (2002), as well as the handle on the console, added to the perception that the GameCube was meant for children—another reason it was avoided by third-parties.[55][70]

The GameCube did not feature any major distinguishing features from its competing consoles, except for acclaimed, console-exclusive games like Super Smash Bros. Melee (2001) and Super Mario Sunshine (2002).[70] Metroid Prime (2002), the first finished game from Retro Studios, saved the studio from potential collapse after they had worked on multiple unfinished game projects. Taking a risk on the studio, Nintendo had then given them the Metroid property to work with. Prime was a success, with multiple publications later labeling it one of the greatest games of all time;[49][71][72] Retro's future was thus secured, and they began development on Metroid Prime 2: Echoes (2004).[49][73]

In September 2002, Nintendo sold its 49% share in Rare to Microsoft, who had Rare develop games for the Xbox.[55][74] This was likely a part of Nintendo's strategy to not rely on second-party development. Instead, the company would better utilize its subsidiaries like HAL Laboratory, and fund third-party development using a financial "war chest" that Yamauchi had started building.[75] Rare had also accounted for little of Nintendo's profits for 2001 and 2002. Industry commentators, as well as Rare designer Martin Hollis, later criticized Nintendo's decision to sell the studio, either because they consider Rare's releases on the original Xbox and Xbox 360 to be subpar, or they believe Nintendo removed themselves of a valuable asset.[76][77][78][79]

Nintendo's aggressive business tactics in Europe caught up to them in October 2002, when the European Commission determined that they had engaged in anti-competitive price-fixing business practices, dating at least as far back as the early 1990s. This resulted in a heavy fine being laid against the company: €149 million, one of the largest antitrust fines applied in the history of the commission.[80]

Nintendo was kept afloat in this era by its sales from the handheld market,[55] which they had "essentially cornered".[81] In January 2003, an updated version of the GBA, the Game Boy Advance SP, was announced. It released in Japan in February, and in the U.S. in March 2003.[82] The N-Gage handheld console, developed by Finnish technology company Nokia, tried to compete with the GBA when the former launched in October 2003, but it was unsuccessful.[83][84]

Nintendo temporarily halted production of the GameCube during the summer of 2003, as the company needed to sell models of the system that were filling up warehouses. At the same time, Iwata announced that the company would stop making "increasingly sophisticated and time-consuming games" in response to the industry-wide decline in video game sales in 2002. Nintendo had also started experiencing competition from the Xbox.[85] Nintendo of America allocated $100 million to selling the GameCube for the 2003 holiday season, and dropped its price to $99.99—way below the Xbox and PS2, which were $179.99.[86] Despite this change, the system was still Nintendo's lowest selling console at the time, being far outpaced by the PS2, which sold 118 million more units than the GameCube, at 21 million.[58][70]

Third-party developer Capcom, who historically had a "rather close relationship" with Nintendo, released Resident Evil 4 (2005) as a GameCube exclusive upon launch; it was initially one of the "Capcom Five", five games that were promised by Capcom in December 2002 to be GameCube exclusives.[87][55] Luke Plunkett writes for Kotaku that in January 2003, the promise was revealed to be "the result of some PR miscommunication, and not an act of corporate benevolence" towards Nintendo, when Capcom stated that the four games besides Resident Evil 4 were planned to be multi-platform. Eventually, Resident Evil 4 also released for the PS2.[87]

In 2003, Nintendo and Chinese-American scientist Wei Yen co-founded the company iQue, a joint venture to manufacture and distribute official Nintendo games within mainland China.[88] In 2000, the country's Ministry of Culture had banned the sale of game consoles within China. This led national video game sales to be made up of pirated games running on counterfeit consoles. Wishing to combat piracy of their games, Nintendo created iQue to work with the government to legally sell games for the China-exclusive gaming console, the iQue Player. Only 14 games were released for the system. The iQue Player was ultimately unsuccessful, in terms of its own sales, as well as combating piracy.[89] However, iQue still sells Nintendo games in China to this day.[90] By 2011, the Ministry's ban had become so minimally enforced that Sony and Microsoft had started selling their consoles as they would in other countries.[89]

Also in 2003, Reggie Fils-Aimé—the future president and CEO of Nintendo of America—joined the company as the executive vice president of sales and marketing for the America division. Before that, he had been on the marketing teams of Panda Express, Pizza Hut, and Procter & Gamble, among other companies.[91]

2004–2011: Nintendo DS and Wii era

[edit]

In 2004, Satoru Iwata restructured Nintendo by replacing the company's four Research & Development divisions with four new divisions, one of them being Nintendo EAD, which was kept in operation. Still led by Miyamoto, EAD was now split into eight teams (EAD 1-8) who each developed separate games. The employees of the previous Research & Development 1 and 2 games were put into EAD. Two departments were made to work on hardware: Integrated Research & Development (IRD) for consoles, and Research & Engineering Development (RED) for handhelds. The fourth division, Software Planning & Division (SPD), developed titles with smaller scopes than the EAD teams, and supervised external first-party development (employees within Nintendo but based outside their Kyoto office). This structure existed until 2015.[30][31]

At Nintendo's E3 2004 press conference, Iwata announced the "Revolution", the codename for the GameCube's successor, which was ultimately named the "Wii". The Revolution started development shortly after the GameCube's launch, and was made as a "small, quiet and affordable" console, which did not prioritize graphical power. Iwata claimed graphics were not as important to the console as the gameplay of its titles, saying the latter would cause a "gaming revolution".[92]

Nintendo also revealed the Nintendo DS handheld at E3, saying that the system displayed games on either or both of two screens, one screen above the other. The system can be folded closed when its user is not playing. The company announced that the DS could: use Wi-Fi to wirelessly communicate with 15 other nearby devices; support a new 3D graphics engine; play multiplayer modes of games they do not own through wireless connectivity, provided a nearby device is running the game (like the GBA Link Cable, except wireless); receive messages from nearby devices; and play GBA cartridges. Also detailed was a microphone, which allows players to interact with DS games audibly. Tony Smith wrote for The Register that the new connectivity features implied "Nintendo is thinking beyond the console to a more general youth-oriented communications device". The company said that 100 developers had signed up to make games for the DS.[93]

In September 2004, Nintendo announced that the DS would launch on November 21 in the U.S. (at $149.99); then Japan; and by the first quarter of 2005, Europe and Australia. IGN wrote that the DS was launching in the U.S. due to significant consumer excitement in the country, and so the launch was to benefit from the 2004 American holiday season. The company also noted that despite playing GBA games, the DS would not include a Link Cable port, so it could not play GBA games' system-link multiplayer modes. PictoChat, a text- and drawing-based messaging app between nearby DS systems which was installed on every device, was revealed as the aforementioned form of wireless messaging. Nintendo had begun development on twenty games for the system.[94]

Nintendo targeted the DS at a demographic of teenagers and young adults, and tried to prevent this new audience from perceiving the device as being meant for the company's traditional, younger demographic. In the U.S., before the DS' launch, the system was advertised with a series of sexually suggestive TV commercials, featuring the tagline "Touching is Good."[95][96][97]

Nintendo was overwhelmed by the number of DS pre-orders. On November 2, 2004, the company halted further pre-orders for the system—it was reported on the 15th that two million handhelds had been ordered, whereas Nintendo had only prepared one million to be available at launch. By that point, two factories in China had been allocated to produce the DS; on November 16, it was reported that Nintendo added a third to meet consumer demand.[98][99][100] The system launched with seven games, two of them developed by Nintendo: the pack-in game Metroid Prime Hunters: The First Hunt (a demo version of the 2006 game Metroid Prime: Hunters), and a remake of Super Mario 64.[101][102] Shortly after, Nintendo competed in the handheld field when Sony released the PlayStation Portable in Japan in December 2004.[103][104]

On May 14, 2005, Nintendo opened its first retail store accessible to the general public, Nintendo World Store, at the Rockefeller Center in New York City. It consists of two stories, and contained many kiosks of GameCube, Game Boy Advance, and Nintendo DS games. There are also display cases filled with things from Nintendo's past, including hanafuda cards. They celebrated the opening with a block party at Rockefeller Plaza.

On May 17, 2005, at E3, Nintendo showed the Revolution's design, though not its eventual motion-sensing controller. They said the console would launch in 2006—notably, this was after the Xbox 360 and PlayStation 3 (PS3)'s releases in late 2005. The Revolution would have online gaming through Wi-Fi, and could run GameCube games. Iwata said the system would be "where the big idea can prevail over big budgets"; Neal Ronaghan later wrote for Nintendo World Report that in hindsight, this was likely referring to the system's motion-controlled games. The company said their plan with the DS and Revolution was to make games for both Nintendo's traditional audience, and a potential wider audience of casual gamers.[105][106] They also revealed the Game Boy Micro: a smaller version of the GBA with a brighter screen, and a faceplate which could be easily detached and replaced with a different design. The Micro was announced for release that fall.[107][108]

On September 16, 2005, at the Tokyo Game Show, Nintendo revealed the design for the Revolution's controller, later named the Wii Remote, which was shaped like a TV remote and could be controlled alongside an attachable joystick; the latter device was later named the Wii Nunchuck. The controller can be held vertically like a TV remote, or horizontally like a traditional gaming controller. Nintendo said that they intended it to be understood by both traditional and casual gamers, and with its internal gyroscope, to be used for motion control within games. The Register wrote that the controller seemed to represent Nintendo moving away from competing with Sony and Microsoft, whose consoles "are likely to be pitched heavily toward hard-core gamers."[109][110]

In January 2006, Nintendo announced a new version of the DS which had been in development since the handheld's launch, the Nintendo DS Lite. It was two-thirds smaller and 20% lighter than the original system, with a brighter screen. The brightness could be adjusted to one of four different levels.[111][112] The DS Lite released in Japan on March 2, 2006,[113] and in North America and Europe on June 11 and 23, 2006, respectively.[114][115]

In April 2006, Nintendo announced that the Revolution would release as the "Wii". The name, like the rest of the console, was intended to appeal to casual audiences, and it initially was highly controversial among Nintendo's fans.[116] Lucas Thomas later wrote for IGN: "Nintendo smartly let the name be known months before 2006's actual E3 show, anticipating that the oddity of it would ignite a firestorm of controversy" [...] "the name would have overshadowed everything else about the system at the show."[117]

Do you know anyone who's never watched TV, never seen a movie, never read a book? Of course not. So let me ask you one more question. Do you know someone, maybe even in your own family, who's never played a video game? I bet you do. How can this be? If we want to consider ourselves a true mass medium, if we want to grow as an industry, this has to change.

In May 2006, at Nintendo's E3 press conference, the company announced that the Wii would release by the end of the year, and revealed multiple games they had developed for the console that used motion controls, including Excite Truck (2006), Wii Sports (2006), and Super Mario Galaxy (2007). Lucas Thomas wrote that these games' E3 demos showcased "effortless" and "crucially different" implementations of motion control, which helped assuage the gaming community's skepticism towards the "shocking and surprising" concept behind the Wii. The positive reception to Nintendo's E3 showing, Thomas said, was also motivated by comparison to Sony's press conference that year, which "infamously bombed".[117]

On May 25, 2006, Reggie Fils-Aimé was promoted to president and CEO of Nintendo of America, Inc. The former president of the division, Tatsumi Kimishima, was promoted to chairman of the board and CEO.[118] On July 7, 2006, Nintendo officially established a South Korean subsidiary, Nintendo Korea, in the country's capital, Seoul, replacing Daewon Media as the official distributor of Nintendo products there.[119]

In early August 2006, it was revealed that Nintendo, along with Microsoft, was made the target of a patent-infringement lawsuit. Leveled by the Anascape Ltd., the suit claimed that Nintendo's use of analog technology in their game controllers constituted a violation of their patents. The lawsuit sought to recover damages from both corporations and possibly force them to stop selling controllers with the violating technology.[120] Microsoft settled with Anascape, while Nintendo went to trial, initially losing and being ordered to pay US$21 million in damages.[121] Nintendo appealed, and on April 23, 2010, the Federal Circuit reversed the ruling.[122] In November 2010, Anascape's appeal to the Supreme Court of the United States was denied.[123]

In September 2006, Nintendo announced launch details for its Wii console, and demonstrated features of the "Wii Menu" GUI. The system was first released in November in the U.S., followed by Japan, Australia, and Europe in December.[124] The console sold fast and was a big breakthrough for Nintendo,[125] picking up the pace lost from the GameCube. Its unexpected success was attributed to the expanded demographic Nintendo had targeted. In response to the Wii, in 2010, Sony and Microsoft released various PS3 and Xbox 360 add-ons targeting the same wider demographic as Nintendo.[126]

In 2007, Nintendo stopped making first-party games for the GameCube.[58]

In September 2007, Nintendo of America indefinitely closed its official Internet forum, the NSider Forums, during a major redesign of their website. For months prior, cutbacks in Nintendo of America's online department led to the trimming back of NSider's chat hours and the replacement of their annual Camp Hyrule event—held during August—with a sweepstakes. In the meantime, Nintendo encouraged fans to run their own forums. Nintendo-Europe's forum section of their site was also officially closed down a week later due to a site revamp, however it had been offline citing "security issues" since June of that year. In December 2007, Nintendo opened a forum for technical support only.

In October 2007, Nintendo announced Nintendo Australia's new managing director, Rose Lappin. She is Nintendo's first female head of one of its subsidiaries and worked for Nintendo before it started in Australia as Director of Sales and Marketing for Mattel and had that role until she was announced managing director.

On November 1, 2008, Nintendo released an updated version of the Nintendo DS Lite in Japan; the Nintendo DSi. It includes all features of the Nintendo DS Lite, but it includes a camera on the inside and outside of the system, and newer features. It is the first handheld game system manufactured by Nintendo that allows downloadable gaming content to the system. The Nintendo DSi was released April 2, 2009, in Australia and Asia, April 3, 2009, in Europe, and April 5, 2009, in North America.

On June 15, 2010, at E3, Satoru Iwata introduced the DS' successor, the Nintendo 3DS. The system, which has the general dual-screen design of the DS, was revealed to allow for autostereoscopic 3D visuals in games, or a way to view 3D visuals without the use of special glasses. The depth of the 3D effect was adjustable through a slider; if the slider is all the way off, the system will display traditional 2D visuals.[127][128][129] Nintendo later stated that the 3D effect should only be used by those older than age seven, as it could cause eye fatigue or headaches for younger players.[130][131] The announcement detailed gyro and motion sensors, as well three cameras built into the system: one on front of the 3DS (when opened) and two on the back—the latter two could be used to take photos viewable in 3D. That E3, 70 games—including mini-games and demos—were shown off or announced to be in development for the 3DS.[127][128][129][132] In September 2010, Nintendo announced the 3DS would first launch in Japan on February 26, 2011, at ¥25,000.[133]

2011–2017: Nintendo 3DS and Wii U era

[edit]

The 3DS includes StreetPass, a feature that allows two nearby 3DS systems to exchange data over Wi-Fi when both systems are in sleep mode (turned on when its screens are closed). This was implemented in some games as a way for two systems to essentially have online multiplayer gaming without either user's involvement. This included the racing game Asphalt 3D (2011), where two systems both running the game can simulate a race by comparing the two players' fastest lap times on a given race track, and awarding the fastest player. The 3DS can also stream 3D videos, such as movies in 3D that were available on Netflix (until the 3DS version of Netflix shut down in 2021).[134][135]

In January 2011, Nintendo announced that the 3DS would launch in the U.S. on March 27, 2011, at $249.99.[136] Upon its launch, the system was generally acclaimed. Kevin Ohannessian wrote for Fast Company that it was a "remarkable gaming machine",[134] but that it was too expensive in the U.S., and its display resolution and battery life were inferior to other handhelds, even the PSP from 2004.[137] Seth Schiesel wrote for The New York Times that the 3D effect was surprisingly immersive and comfortable to him over long periods of use.[138] The system's sales started off slowly. In the U.S., the 3DS had a "reasonably strong launch", but, in part due to its price, it sold a relatively low 110,000 units during its second quarter on the market.[139] Nintendo responded by dropping the U.S. price to $169.99 in June 2011; this helped the 3DS rebound, ultimately selling 4.5 million units over the course of its first year in the U.S. The company simultaneously dropped the Japanese price to ¥15,000.[139][140]

In April 2011, Nintendo announced a successor console to the Wii, giving it the codename "Project Cafe". Details on the console came at the company's E3 press conference on June 7, 2011, where it was revealed to be named the "Wii U". Chris Zeigler wrote for The Verge: "Nintendo says [the "Wii U"] name underscores the fact that the gaming experience is all about you". The console was partially the traditional "box" with a processor that connects to a monitor such as a TV, but the Wii U's distinguishing feature was the Wii U GamePad. The GamePad is a touchscreen display and controller, which includes a microphone, gyroscope, and camera, and which is wirelessly connected to the "box". Nintendo showed the GamePad's display having many possible implementations in games, such as displaying the perspective of a rifle scope in a game, magnfiying details of a TV depending on which area of the TV the GamePad's gyroscope was aimed at. The company also said the console would output high-definition video (HD), be backwards compatible with Wii games and accessories, and support some form of video conferencing.[141]

Nintendo enjoyed continued success in the handheld market, with the 3DS selling 75 million units during its decade-long run. By contrast, the Wii U suffered confusing marketing, a lack of third-party support, and very slow consumer adoption. Thus Nintendo experienced declining revenues throughout the mid-2010s. Nintendo discontinued the Wii U in 2017 as the lowest-selling Nintendo home console, with only about 13.5 million units sold.

In May 2013, Nintendo started copyright claiming "Let's Play" videos of their games on YouTube—claiming future advertising revenue generated by video recordings of gameplay, which had, until then, created revenue for whoever uploaded it. Claiming copyright on a YouTube video via a "Content ID Match" had been previously done by the owners of music and film intellectual properties to receive revenue from song uploads or movie clips on the site, but Nintendo's decision to do so for gameplay videos was controversial.[142][143][144] Many in the gaming community argued that gameplay was, in this context, created by the person who played the game, and thus not the financial property of Nintendo.[142][145] Nintendo started removing these claims in June 2013.[146]

On July 11, 2015, Satoru Iwata died from a bile duct tumor at 55. On September 16, Nintendo named Tatsumi Kimishima as his replacement.

During the Nintendo 3DS and Wii U era, Nintendo's profits fell to lows not seen during their history as a video game manufacturer,[147] reporting their first net loss as a video game company in 2012.[148] Though initially claiming that mobile gaming was incompatible with Nintendo's identity,[149] Iwata established a partnership with mobile developer DeNA to create mobile games based on Nintendo properties prior to his death.[150][151]

2017–present: Nintendo Switch era

[edit]

After beginning the conceptual phase of development in 2012,[152] Nintendo announced in a March 2015 press conference that they were developing a dedicated video game system, codenamed "NX".[153] Fils-Aimé said in 2021 that the system was a "make or break" console for the company, as it became apparent that the Wii U's lifespan would be considerably shorter than average.[154] In April 2016, they revealed that the NX was set for a March 2017 release.[155] The NX was formally unveiled as the "Nintendo Switch" in October 2016, a hybrid console able to switch between portable and home console play.[156] In a January 2017 event, Nintendo revealed more details about the Switch.[157]

The Switch was released on March 3, 2017.[158][159] It launched with 15 titles, five of them exclusive to the Japanese eShop. Three of them were developed by Nintendo and released worldwide: 1-2-Switch, Snipperclips, and The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild.[160] The latter released simultaneously on the Wii U, and was a massive critical success; it was later named the best video game of all time by IGN,[161] British GQ magazine,[162] and Rolling Stone magazine.[72]

Following the failure of the 1993 Super Mario Bros. film, Nintendo was wary of creating films based on their franchises,[163] though the Virtual Console service inspired them to pursue other utilizations of their popular software, including film.[164] A partnership between Nintendo and Sony Pictures for an animated Mario film was leaked in 2014,[163] though Nintendo announced in January 2018 that they would be partnering with Illumination to produce an animated Mario film, produced by Miyamoto and Chris Meledandri, and distributed by Universal Pictures.[165] Titled The Super Mario Bros. Movie, the film was released on April 5, 2023,[166] starring Chris Pratt as Mario.[167]

In April 2018, Shuntaro Furukawa succeeded Kimishima as Nintendo's president,[168] and in February 2019, Doug Bowser replaced Fils-Aimé as President and COO of Nintendo of America.[169] In April 2019, Tencent received approval to sell the Switch in China,[170] and the console released there that December.[171]

In January 2020, hotel and restaurant development company Plan See Do announced their intent to refurbish the former headquarters of Marufuku Nintendo as a hotel set to open midway through 2021,[172] and in June 2021, Nintendo announced that the Uji Ogura plant in which the company's playing cards were produced would be transformed into a museum titled the "Nintendo Gallery", to be completed by the end of the 2023 fiscal year.[173]

ValueAct Capital, a San Francisco-based investment firm, announced in April 2020 that they had purchased US$1.1 billion worth of Nintendo stock, or a 2% stake of the company.[174] Nintendo announced its acquisition of SRD Co., Ltd. in February 2022, who had worked with Nintendo for over 40 years, primarily as a support studio.[175] In May 2022, the Public Investment Fund of the Saudi government purchased a 5% stake in Nintendo.[176] Furukawa claimed in February 2021 that the Nintendo Switch was "in the middle of its life cycle".[177]

In 2021, Furukawa said Nintendo plans to explore animated adaptations of their franchises beyond The Super Mario Bros. Movie.[178] In July 2022, the company announced its acquisition of the Japanese animation studio Dynamo Pictures, Inc.,[179] and renamed the studio to Nintendo Pictures Co., Ltd. following the closure of the acquisition in October 2022.[180]

Nintendo announced the Nintendo Switch's successor, the Nintendo Switch 2, on January 16, 2025. The new console is expected to launch later in the year. A Nintendo Direct about the new system will be on April 2, 2025.

In March 2025, the developer of Pokémon Go, Niantic, Inc., sold the game's rights to Scopely, a game developer and publisher which is owned by Saudi Arabia's Public Investment Fund.[181][182]

Logo history

[edit]-

1889-1957

-

1963-1971

-

1970-1974

-

1972-1984

-

1984-2004 (primary); 2004-present (secondary)

-

2004-2016 (primary); 2016-present (secondary)

-

2016–present

References

[edit]- ^ "Nintendo's old and new HQ (headquarters) in Kyoto". Sharing Kyoto. March 10, 2021. Retrieved June 7, 2023.

- ^ "任天堂株式会社:会社の沿革". 任天堂ホームページ (in Japanese). Retrieved September 27, 2019.

- ^ "Nintendo Trademark". December 5, 2009. Archived from the original on October 29, 2010.

- ^ ""Nintendo" Might Not Mean What You Think". Gizmodo. Retrieved May 8, 2013.

- ^ Life, Nintendo (April 11, 2016). "How One Man Saved Kyoto - And Video Games - From The Atomic Bomb". Nintendo Life. Retrieved March 10, 2025.

- ^ "Nintendo History". Nintendo.co.uk. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ^ "Profile: Hiroshi Yamauchi". N-Sider.com. Archived from the original on September 19, 2015. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ^ "Securities Report" (PDF) (in Japanese). Nintendo. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ^ a b "Nintendo History Lesson". N-Sider.com. Archived from the original on May 5, 2018. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Company History". Nintendo.co.jp. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ^ Kohler, Chris (September 23, 2010). "Sept. 23, 1889: Success Is in the Cards for Nintendo". Wired.com. Wired. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ^ Ashcraft, Brian (March 22, 2011). "The Nintendo They've Tried to Forget: Gambling, Gangsters, and Love Hotels". Kotaku. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ^ Kohler, Chris (September 19, 2013). "Hiroshi Yamauchi, man who built Nintendo's gaming empire, dies at 85". Wired. Retrieved February 15, 2022.

- ^ Daniels, Peter W.; Ho, K.C.; Hutton, Thomas A. (April 27, 2012). New Economic Spaces in Asian Cities: From Industrial Restructuring to the Cultural Turn. Taylor & Francis. p. 97. ISBN 9781135272593.

- ^ a b Pollack, Andrew (October 9, 1997). "Gunpei Yokoi, Chief Designer Of Game Boy, Is Dead at 56". The New York Times. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ^ History of Nintendo - Toys & Arcades (1969 - 1982) Archived March 29, 2010, at the Wayback Machine (archived[dead link]), Nintendo Land

- ^ Voskuil, Erik (February 20, 2011). "Nintendo Light-beam games Kôsenjû SP and Kôsenjû Custom (光線銃SP, 光線銃 カスタム 1970-1976)". Before Mario. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ^ Voskuil, Erik (February 1, 2014). "What does the Nintendo Ele-conga sound like?". Before Mario. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ^ The Ten Greatest Years in Gaming Archived April 19, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Edge June 27, 2006, Accessed March 1, 2009

- ^ Martin Picard, The Foundation of Geemu: A Brief History of Early Japanese video games, International Journal of Computer Game Research, 2013

- ^ a b c "Nintendo: Company History". Archived from the original on February 5, 1998. Retrieved December 18, 2014.

- ^ "Iwata Asks-Punch-Out!!". Nintendo. Archived from the original on August 10, 2009. Retrieved July 7, 2009.

- ^ "Coin-Op "Super Mario" Will Shop To Overseas" (PDF). Amusement Press. March 1, 1986. Retrieved June 20, 2022.

- ^ ""Fami-Com" Exceeds 10M. Its Boom Is Continuing" (PDF). Amusement Press. May 1, 1987. Retrieved June 20, 2022.

- ^ "Nintendo Co. Withdrew From JAMMA" (PDF). Amusement Press. April 1, 1989. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- ^ Sheff, David (November 2, 2011). Game Over: How Nintendo Conquered The World. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-80074-9.

- ^ "The Game System That Almost Wasn't". Nintendo Power Source. Nintendo of America. Archived from the original on October 12, 1997. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- ^ Turner, Benjamin; Nutt, Christian (July 2003). "Uphill Struggle". Nintendo Famicom: 20 Years of Fun!. GameSpy. p. 12. Archived from the original on August 5, 2004. Retrieved July 25, 2009.

- ^ Cifaldi, Frank (October 19, 2015). "In Their Words: Remembering the Launch of the Nintendo Entertainment System". IGN. Retrieved July 1, 2019.

- ^ a b Karvande, Harshal (May 26, 2024). "Nintendo's Game Teams Explained". Naavik. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ a b "Nintendo EAD (Company)". Giant Bomb. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ "Nintendo Power". Nintendo. Archived from the original on December 6, 2012. Retrieved December 4, 2012.

- ^ a b "Hardware and Software Sales Units". Nintendo.co.jp. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ^ "Chronology of Nintendo Video Games (1988-1989)." Chronology of Nintendo Video Games (1988-1989). N.p., n.d. Web. August 7, 2015.

- ^ Craig Glenday, ed. (2008). Guinness World Records Gamer's Edition 2008. Guinness World Records. section coauthored by Oli Welsh. Guinness World Records Limited. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-904994-20-6.

- ^ Shapiro, Eben (June 1, 1991). "Nintendo Goal: Bigger-Game Hunters". The New York Times. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ^ "History | Corporate". Nintendo. Retrieved December 18, 2014.

- ^ Retro Gamer staff (2013). "Sonic Boom: The Success Story of Sonic the Hedgehog". Retro Gamer — the Mega Drive Book. London, UK: Imagine Publishing: 31.

The game and its star became synonymous with Sega and helped propel the Mega Drive to sales of around 40 million, only 9 million short of the SNES—a minuscule gap compared to the 47 million that separated the Master System and NES.

- ^ "Nintendo Price-Fixing Case Settled". Seattle Times. April 11, 1991. Archived from the original on October 3, 2012. Retrieved August 10, 2011.

- ^ "Nintendo Will No Longer Produce Coin-Op Equipment". Cashbox. September 5, 1992. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- ^ "Nintendo Stops Games Manufacturing; But Will Continue Supplying Software". Cashbox. September 12, 1992. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- ^ "Yamauchi Buys Mariners As A Public Service". The Spokesman-Review. Associated Press. June 11, 1992. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ^ "the debate over video games". New Straits Times. May 8, 1993. Retrieved August 6, 2019.

- ^ "Nintendo Dealt Blow". Next Generation. No. 35. Imagine Media. November 1997. p. 22.

- ^ Massey, Tom (October 27, 2013). "The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time retrospective". Eurogamer.net. Retrieved March 12, 2025.

- ^ Mitra, Ritwik (November 7, 2022). "6 Games That Punish You For Overusing The Camera Lock-On Feature". Game Rant. Retrieved March 12, 2025.

- ^ a b "The Essential 50 Part 40: The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time from 1…". archive.ph. July 18, 2012. Retrieved March 12, 2025.

- ^ "Most critically acclaimed videogame ever". Guinness World Records. Retrieved March 11, 2025.

- ^ a b c Hester, Blake (May 29, 2018). "The rocky story of Retro Studios before Metroid Prime". Polygon. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ Silberman, Steve. "Zelda Gets Naughty". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved June 16, 2024.

- ^ Margolis, Jonathan (December 29, 1999). "Nintendo faces £60m writ from Uri Geller". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved June 16, 2024.

- ^ "Geller sues Nintendo over Pokemon". November 2, 2000. Retrieved June 16, 2024.

- ^ Carpenter, Nicole (November 30, 2020). "Magician ends 20-year battle with Nintendo over Pokemon card". Polygon. Retrieved June 16, 2024.

- ^ Kohler, Chris. "Akihabara Buys: The Rarest Games For Nintendo's Failed 64DD". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved March 15, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Hardware Classics: Nintendo GameCube". Nintendo Life. September 14, 2021. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ a b "BBC News | BUSINESS | Nintendo reveals new GameCube". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved June 16, 2024.

- ^ a b "What's inside the GameCube?". ZDNET. Retrieved June 16, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e "The Nintendo GameCube Is Twenty Years Old Today". GameSpot. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ "Nintendo to issue protective game gloves". ZDNET. Retrieved June 16, 2024.

- ^ "Nintendo Shuts Down Pirates". GameSpot. Retrieved June 16, 2024.

- ^ "BBC News | SCI/TECH | Nintendo to hand out gaming gloves". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved June 16, 2024.

- ^ a b "Game Boy Advance Breaks Sales Records". ABC News. Retrieved June 16, 2024.

- ^ Whitehead, Dan (September 9, 2019). "Dreamcast: A Forensic Retrospective". Eurogamer.net. Retrieved March 14, 2025.

- ^ "Sonic: The Nintendo Years - Part One". Nintendo Life. June 23, 2011. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ "CNN.com - Sony, Nintendo pumped to beat the Xbox - May 17, 2001". www.cnn.com. Retrieved March 14, 2025.

- ^ Gaither, Chris (November 30, 2001). "Technology Briefing | Hardware: Strong Gamecube Sales Reported". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ "GameCube sales brisk - Nov. 29, 2001". money.cnn.com. Retrieved June 16, 2024.

- ^ "Nintendo Of America President Retires, Replaced By Pokemon USA Exec". Gamasutra. January 8, 2002. Retrieved February 19, 2015.

- ^ Walker, Trey (May 24, 2002). "E3 2002: Yamauchi steps down". GameSpot. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Schneider, Peer (March 27, 2014). "Nintendo GameCube - History of Video Game Consoles Guide". IGN. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ Staff, I. G. N. (December 31, 2021). "The Top 100 Video Games of All Time". IGN. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ a b Stone, Rolling (January 6, 2025). "The 50 Greatest Video Games of All Time". Rolling Stone. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ Life, Nintendo (November 15, 2024). "Anniversary: 20 Years On, Metroid Prime 2 Represents The Franchise At Its Experimental Best". Nintendo Life. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ "Who Killed Rare?". Eurogamer.net. February 8, 2012. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ "Nintendo confirms Rare sale". Eurogamer.net. September 23, 2002. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ Mason, Graeme (August 7, 2023). "The Ultimate-Rare story: 40 years of brilliant British games, from Jetpac and GoldenEye to Sea of Thieves". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ Life, Nintendo (August 4, 2015). "Rare Co-Founder Has No Idea Why Nintendo Didn't Buy The Studio Outright". Nintendo Life. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ Kurland, Daniel (October 14, 2021). "5 Ways Nintendo Should Regret Letting Rare Go (& 5 They Shouldn't)". CBR. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ B2B, Christopher Dring Head of Games (January 30, 2020). "Who saved Rare?". GamesIndustry.biz. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Nintendo fined for price fixing". BBC News. October 30, 2002. Retrieved March 11, 2007.

- ^ "Sony, Nintendo unveil new handhelds". NBC News. May 11, 2004. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ Harris, Craig (January 6, 2003). "Game Boy Advance SP". IGN. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ "New worries for Nintendo". NBC News. October 6, 2003. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ Frommer, Dan. "Nokia To Kill Off Lame N-Gage Gaming Project". Business Insider. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ "Nintendo stops GameCube production". August 8, 2003. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ "Nintendo makes $99 GameCube official". GameSpot. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ a b "Remembering Capcom's Great Nintendo Promise / Betrayal". Kotaku. May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ "Nintendo to Enter China's Video-Game Market With a New Console". Bloomberg.com. September 25, 2003. Retrieved December 18, 2014.

- ^ a b Rose, Janus (October 7, 2011). "The Nintendo Console That Fought Chinese Piracy, And Lost". VICE. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ Barder, Ollie. "Nintendo President Shuntaro Furukawa On Releasing The Switch In China And The Status Of The 3DS". Forbes. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ "Reggie Fils-Aime promoted to NOA president - Joystiq". web.archive.org. June 14, 2006. Retrieved March 9, 2025.

- ^ Casamassina, Matt (September 12, 2005). "IGNcube's Nintendo "Revolution" FAQ". IGN. Retrieved December 13, 2024.

- ^ "Nintendo DS: more communicator than console?". Archived from the original on January 12, 2025. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ Harris, Craig (September 21, 2004). "Official Nintendo DS Launch Details". IGN. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ "Nintendo DS targets teens, young adults". NBC News. November 15, 2004. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ "Nintendo launches new handheld". NBC News. November 20, 2004. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ "Nintendo ads take on sexual overtone". NBC News. October 25, 2004. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ Joel (November 15, 2004). "Nintendo DS Preorders at 2 Million". Gizmodo. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ zmcnulty (November 2, 2004). "GameStop Stops Nintendo DS Preorders". Gizmodo. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ "Nintendo adds third DS factory due to demand". Engadget. November 16, 2004. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ Swan, Cameron (January 3, 2023). "Remembering the Nintendo DS' Launch Titles". Game Rant. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ "20 Years Ago, Nintendo Released A Near-Perfect Remake With One Glaring Flaw". Inverse. November 23, 2024. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ "Nintendo, Sony start pre-holiday push". NBC News. September 23, 2004. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ "Sony, Nintendo unveil new handhelds". NBC News. May 11, 2004. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ "Nintendo's Revolution will have to wait". NBC News. May 16, 2005. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ "A Look Back at Nintendo's E3 2005 Show - Feature". Nintendo World Report. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ "Nintendo unveils new Game Boy". NBC News. May 17, 2005. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ ROUNDUP, A. Wall Street Journal Online NEWS (May 17, 2005). "Nintendo Unveils New Game Boy Device". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ "Nintendo shows 'Revolutionary' console controller". Archived from the original on August 12, 2024. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ Gitlin, Elle Cayabyab (September 16, 2005). "Nintendo's Revolution controller revealed. Is it innovation or insanity?". Ars Technica. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ "Nintendo redesigns the Nintendo DS - Jan. 26, 2006". money.cnn.com. Retrieved March 4, 2025.

- ^ "New DS hitting Japan March 2". GameSpot. Retrieved March 4, 2025.

- ^ "DS Lite hits Japan today...kinda". CNET. Retrieved March 4, 2025.

- ^ Staff, WIRED. "DS Lite: June 11, $129". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved March 4, 2025.

- ^ Krotoski, Aleks (May 22, 2006). "Nintendo DS Lite handheld released 23 June". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved March 4, 2025.

- ^ "Nintendo drops Revolution, renames next gen console Wii - Apr. 27, 2006". money.cnn.com. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ a b Thomas, Lucas M. (May 17, 2011). "Nintendo's History at E3: 2006". IGN. Retrieved March 14, 2025.

- ^ Dobson, Jason (May 25, 2006). "Nintendo Of America's Fils-Aime Promoted to President/COO". Gamasutra. Think Services. Retrieved December 14, 2009.

- ^ Jenkins, David (June 30, 2006). "Nintendo Establishes Subsidiary In South Korea". Gamasutra. Retrieved December 18, 2014.

- ^ "Nintendo, Microsoft Face Patent Lawsuit - DS News at IGN". January 26, 2009. Archived from the original on January 26, 2009. Retrieved October 31, 2012.

- ^ Ricker, Thomas (May 15, 2008). "Nintendo ordered to pay $21 million to patent troll". Engadget. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ^ Kapur, Rajit (April 4, 2010). "Case Update: Anascape, Ltd. v. Nintendo of America Inc". Patent Arcade. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ^ Greenspan, Jesse (November 1, 2010). "Anascape Bid To Reclaim $21M Dashed By High Court". Law360.com. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ^ "Wii European launch details announced". GamesIndustry.biz. September 15, 2006. Retrieved December 18, 2014.

- ^ "Nintendo Predicts Holiday Wii Shortage - Yahoo! News". archive.ph. October 17, 2007. Archived from the original on October 17, 2007.

- ^ Gaudiosi, John (April 25, 2007). "The untold story of how the Wii beat the Xbox, PlayStation". CNN.com. Retrieved December 18, 2014.

- ^ a b "Nintendo introduces 3-D game machine". NBC News. June 15, 2010. Retrieved March 9, 2025.

- ^ a b "Gut Reactions: Nintendo 3DS - E3 2010". GameSpot. Retrieved March 9, 2025.

- ^ a b published, Brett Elston (June 17, 2010). "E3 2010: Hands-on with Nintendo 3DS". gamesradar. Retrieved March 9, 2025.

- ^ "Nintendo Warns Parents Of Eye Risks In 3-D Game". NPR. Retrieved March 11, 2025.

- ^ Modojo. "Nintendo 3DS: 3-D Warning Should Not Be Taken Lightly". Business Insider. Retrieved March 11, 2025.

- ^ O’connell, Frank. "A Look Inside the Nintendo 3DS XL". archive.nytimes.com. Retrieved March 11, 2025.

- ^ "3DS Japanese Release Set for February 26, 2011 - News". Nintendo World Report. Retrieved March 9, 2025.

- ^ a b Ohannessian, Kevin (March 25, 2011). "Nintendo 3DS: Controlling Innovation". Fast Company. Archived from the original on September 28, 2024. Retrieved March 11, 2025.

- ^ "Netflix Service Discontinuation (Nintendo 3DS & Wii U) | Nintendo Support". en-americas-support.nintendo.com. Retrieved March 11, 2025.

- ^ Ewalt, David M. "Nintendo Announces 3DS Launch Date, Price". Forbes. Retrieved March 9, 2025.

- ^ Ohannessian, Kevin (January 20, 2011). "Nintendo 3DS: The Agony and the Ecstasy". Fast Company. Retrieved March 11, 2025.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Schiesel, Seth (March 25, 2011). "How It Plays: Taking a New System Out for Several Spins". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 11, 2025.

- ^ a b "How the Nintendo 3DS went from flop to sleeper hit". Yahoo News. March 7, 2012. Retrieved March 11, 2025.

- ^ "Nintendo slashes 3DS price to $169.99". CNET. Retrieved March 11, 2025.

- ^ Ziegler, Chris (June 7, 2011). "Nintendo Wii U announced, coming in 2012 (updated with pictures, video, and specs)". The Verge. Retrieved March 11, 2025.

- ^ a b MacDonald, Keza (May 16, 2013). "Nintendo Enforces Copyright on Youtube Let's Plays". IGN. Retrieved March 9, 2025.

- ^ Gera, Emily (May 16, 2013). "Nintendo claims ad revenue on user-generated YouTube videos". Polygon. Retrieved March 9, 2025.

- ^ "Nintendo mass-claims revenue from YouTube 'Let's Play' videos". Engadget. May 16, 2013. Retrieved March 9, 2025.

- ^ "Nintendo lays claim to YouTube fan videos". CNET. Retrieved March 9, 2025.

- ^ "Nintendo Starting to Reverse YouTube Copyright Claims - News". Nintendo World Report. Retrieved March 9, 2025.

- ^ Nicks, Denver (January 17, 2014). "Nintendo Chief: 'We Failed'". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Archived from the original on December 14, 2019. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- ^ Wingfield, Nick (November 24, 2012). "Nintendo's Wii U Takes Aim at a Changed Video Game World". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 7, 2022. Retrieved November 21, 2018.

- ^ Thomas, Lucas M. (September 13, 2011). "Nintendo + Smartphones? Iwata Says "Absolutely Not"". IGN. Ziff Davis. Archived from the original on July 30, 2017. Retrieved September 3, 2015.

- ^ Peckham, Matt (March 18, 2015). "Exclusive: Nintendo CEO Reveals Plans for Smartphones". Time. Archived from the original on April 23, 2015. Retrieved July 13, 2015.

- ^ Makuch, Eddie (March 18, 2015). "Players More Important Than Money, Nintendo Pres. Says About Smartphone Deal". GameSpot. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ Hester, Blake (December 26, 2017). "How the Polarization Of Video Games Spurred the Creation of the Switch". Glixel. Penske Media Corporation. Archived from the original on December 26, 2017. Retrieved December 26, 2017.

- ^ Yin-Poole, Wesley (March 17, 2015). "Nintendo NX is "new hardware with a brand new concept"". Eurogamer. Gamer Network. Archived from the original on October 20, 2016. Retrieved November 30, 2022.

- ^ Nunneley, Stephany (January 30, 2021). "Reggie: Switch was a "make or break product" for Nintendo that "luckily was a hit"". VG247. Gamer Network. Archived from the original on July 1, 2022. Retrieved January 30, 2021.

- ^ Reilly, Luke (April 27, 2016). "Nintendo NX Will Launch In March 2017". IGN. Ziff Davis. Archived from the original on April 28, 2016. Retrieved April 27, 2016.

- ^ Souppouris, Aaron (October 20, 2016). "'Switch' is Nintendo's next game console". Engadget. AOL Inc. Archived from the original on October 20, 2016. Retrieved October 20, 2016.

- ^ Makuch, Eddie (October 27, 2016). "More Nintendo Switch News Coming in January 2017". GameSpot. Red Ventures. Archived from the original on September 7, 2022. Retrieved December 13, 2022.