Indigenous territory (Brazil)

In Brazil, an Indigenous territory or Indigenous land (Portuguese: Terra Indígena [ˈtɛʁɐ ĩˈdʒiʒẽnɐ], TI) is an area inhabited and exclusively possessed by Indigenous people. Article 231 of the Brazilian Constitution recognises the inalienable right of Indigenous peoples to lands they "traditionally occupy"[n 1][1][2] and automatically confers them permanent possession of these lands.

A multi-stage demarcation process is required for a TI to gain full legal protection,[2][3] and this has often entailed protracted legal battles.[4][5][6] Even after demarcation, TIs are frequently subject to illegal invasions by settlers and mining and logging companies.[2]

By the end of the 20th century, with the intensification of Indigenous migration to Brazilian cities, urban Indigenous villages were established to accommodate these populations in urban settings.

Historically, the peoples who first inhabited Brazil suffered numerous abuses from European colonizers, leading to the extinction or severe decline of many groups. Others were expelled from their lands, and their descendants have yet to recover them. The rights of Indigenous peoples to preserve their original cultures, maintain territorial possession, and exclusively utilize their resources are constitutionally guaranteed, but in reality, enforcing these rights is extremely challenging and highly controversial. It is surrounded by violence, corruption, murders, land grabbing, and other crimes, sparking numerous protests both domestically and internationally, as well as endless disputes in courts and the National Congress.

Indigenous awareness is growing, the communities are acquiring more political influence, organizing themselves into groups and associations and are articulated at national level. Many pursue higher education and secure positions from which they can better defend their peoples’ interests. Numerous prominent supporters in Brazil and abroad have voluntarily joined their cause, providing diverse forms of assistance. Many lands have been consolidated, but others await identification and regularization. Additional threats, such as ecological issues and conflicting policies, further worsen the overall situation, leaving several peoples in precarious conditions for survival. For many observers and authorities, recent advances—including a notable expansion of demarcated lands and a rising population growth rate after centuries of steady decline—do not offset the losses Indigenous peoples face in multiple aspects related to land issues, raising fears of significant setbacks in the near future.

As of 2020[update], there were 724 proposed or approved Indigenous territories in Brazil,[7] covering about 13% of the country's land area.[8] Critics of the system say that this is out of proportion with the number of Indigenous people in Brazil, about 0.83% of the population;[9] they argue that the amount of land reserved as TIs undermines the country's economic development and national security.[6][10][11][12]

Definition

[edit]

Jurists distinguish between Indigenous lands in a broad sense and Indigenous lands in a strict sense. Strictly speaking, Indigenous lands are those defined in the 1988 Constitution as traditionally occupied. In a broader sense, they include those defined in the Indian Statute of 1973, which encompasses traditionally occupied lands, reserved lands (with four categories), and community-owned lands.[15][16]

The Constitution guarantees Indigenous peoples possession of the lands they traditionally or ancestrally inhabit, regardless of their location, with no room for disputes over the feasibility or appropriateness of demarcation as established.[17] However, such disputes are common, as seen in the demarcation of the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous Territory. Only Indigenous lands in the constitutional sense, those traditionally occupied, are subject to the demarcation process. In contrast, a reserved Indigenous land is one allocated by the federal government based on its discretion, which may be subject to judicial review, including considerations of viability and national security. These lands have four categories: Indigenous reserve, Indigenous park, Indigenous agricultural colony, and Indigenous federal territory. Community-owned lands (or proprietary lands) are those owned, not merely possessed, by Indigenous peoples, acquired through purchase or donation.[15]

According to Lívia Mara de Resende’s analysis, all these categories are controversially defined, and their practical application has sparked numerous disputes. There is uncertainty about whether the constitutional provisions for Indigenous lands—such as their inalienability, unavailability, and immunity to adverse possession—apply to reserved lands and community-owned lands. It is also debated whether the special rules in the Indian Statute for Indigenous lands in the broad sense, such as their immunity to adverse possession, remain applicable, given that reserved and community-owned lands are not considered Indigenous lands under the constitutional definition.[15]

| Part of a series on |

| Indigenous rights |

|---|

| Rights |

| Governmental organizations |

| United Nations initiatives |

| International Treaties |

| NGOs and political groups |

| Issues |

| Countries |

| Category |

History and legal framework

[edit]Context of the Conquest

[edit]

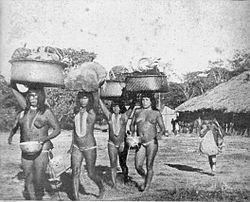

The first humans to inhabit what would become Brazil arrived thousands of years ago. They established deep roots, developed diverse and rich cultures, and by 1500, an estimated 2 to 5 million people lived there.[18][19] That year, however, European conquerors, the Portuguese, reached the coast. Initial contacts appeared friendly, as described in the Letter of Pero Vaz de Caminha, and assistance from some tribes was crucial for the survival of many expeditions and early Portuguese settlements, fostering extensive trade and cooperation on various levels. Some Portuguese were so captivated by the Indigenous way of life that they "went native," living in the forests among them, forming families, and producing descendants, or adopting certain Indigenous customs.[20][21][22][23]

Soon, however, the true intentions of the conquest became evident and increasingly dire. Imposing dominance by any means, the Portuguese subjected the land’s original inhabitants to systematic abuses, including mass murders, torture, and rape, driving survivors deeper into the remote interior. In their wake, they built an entirely distinct civilization and a vast state, where Indigenous peoples were deemed an inferior and incapable race, destined by God to be subdued by the sword and, perhaps, aided by Portuguese culture under the banner of Christ.[19][24][25][26][27] Despite the grandeur and charity embedded in such concepts, they generally served only the Portuguese. They incited rival Indigenous groups to wage war against each other for indirect benefits, used others repeatedly as allies against pirates and French and Dutch invaders, and allowed many villages to exist solely to mark new Portuguese frontiers and, above all, defend them, in the context of territorial expansion beyond Spanish domains and the limited military forces deployed to Brazil. Virtually the entire modern Brazilian Amazon, west of the Tordesillas Line, resulted from the permanent establishment of Indigenous villages transformed into Portuguese strongholds. These involuntary spearheads, such as the Macushi and Wapishana of Roraima, were called the "ramparts of the wilderness".[28][29]

Massacres of resistant and hostile groups, as noted, were frequent, including those during the Guaraní War, the Tamoyo Confederation, the Potiguar revolts, and the Barbarian War, despite various royal and ecclesiastical decrees condemning such abuses. A large population ended their lives as slaves, serving the Portuguese in households, labor, and militias.[22][28][29] After importing African slaves became more profitable, interest in Indigenous labor waned, as they were deemed rebellious and lazy. No longer serving a primary purpose, they became primarily an inconvenience to all.[20][31][32]

Many Portuguese were horrified by the atrocities and sought to defend the Indigenous peoples,[20][22][27][33] and since 1537, the Catholic Church recognized them as "true men".[19] In practice, however, for a long time, the original peoples were often considered brute beings, insensitive to reason, justice, true faith, and noble sentiments, closer to animals than humans, with many doubting they possessed a soul. Throughout colonization, Europeans undertook numerous initiatives to "tame" native peoples and find some "utility" for the colonial project, "for the benefit of His Highness and the Kingdom," settling them in reductions or permanent villages akin to towns and assimilating them into Western civilization. They were taught the religion and customs of the colonizers, always under the assumption that their culture was worthless and should be replaced by a "superior" one, which also promised salvation and eternal life after death. They were seen as blank slates to be written upon at will, as described by Nóbrega, who was nonetheless one of their notable defenders.[26][34][35][36][37] But violence and neglect were not the only tolls: vast populations were decimated by diseases from overseas, such as influenza, measles, whooping cough, tuberculosis, and smallpox, against which their bodies had no natural immunity,[38] and others, addicted to aguardente, a distilled spirit widely distributed by the Portuguese, were ravaged by alcoholism.[22]

The conquest’s impact was profound not only on the original peoples but also on the natural landscape, with extensive deforestation and other environmental changes.[39][40] In the words of former FUNAI president Carlos Marés de Souza Filho,

- "The Europeans, especially the Portuguese and Spanish, arrived in America as if expanding their agricultural frontiers. They extracted wealth, devastated the soil, and replaced the natural environment with one they knew and controlled. The local populations lived off what was here, eating corn or cassava, producing biju, rich meats from native animals, birds, or fish. Gradually, new foods were introduced—goats, sheep, cheeses—and new plants, like sugarcane, coffee, and beets. The introduction of new species spared neither trees nor fruits, to the point that it could be said the natural world was replaced."[27]

The reductions established by missionaries, particularly the Jesuits, where Indigenous peoples were gathered into relatively self-sufficient communities under the protection of priests and the Crown, were a lifeline for many, sparing them much brutality. However, numerous reductions were destroyed by other colonizers, and the true value of this protection is debated, as it often meant the dissolution of traditional cultures and conversion to a European way of life.[27][33][34][35][36] This is evidenced by the views of other religious protectors, even less flattering than Nóbrega’s, revealing irreconcilable cultural differences that inevitably worked to the Indigenous peoples’ detriment. For example, Father Cardiel of the southern Guaraní reductions stated that "the least dull Indians had only brief moments of awareness," while the renowned Father Sepp, active in the same region, described the reduced Indians as "stupid, coarse, utterly coarse in all spiritual matters." There is no documentary evidence of any priest forming a close personal friendship with an Indian; no Jesuit writer ever claimed to have learned anything from the peoples they led, nor acknowledged any significant contribution from native culture to the emerging society in the reductions. Rather, tolerance of some Indigenous customs was a diplomatic and pedagogical concession that, with the progress of forced acculturation, would become unnecessary, superseded by the new cultural and social reality intended for the future.[41][42] Nonetheless, they generally recognized the Indians’ remarkable artistic talent and deep capacity for emotional devotion and personal loyalty.[43][44][45][46]

Early Protection Laws

[edit]

With the establishment of the General Government in Salvador in 1549, the first regulations concerning Indigenous peoples emerged in a Regimento that ensured protection for Crown allies and granted Jesuits significant influence over Indigenous affairs.[20] In 1680, a Royal Decree established the indigenato, recognizing the inherent and primary right of native peoples to their traditional territories.[15][24] Consequently, all land grants to settlers were to "reserve the rights of the Indians." However, the concept of a "reserve" remained vague,[15] and the indigenato initially applied only to Indigenous peoples in Pará and Maranhão.[47] As a result, the decree had limited impact, and European expansion onto Indigenous lands continued unabated. The Portuguese state itself, which issued the decree, often actively or passively supported exploitation. For instance, the Diretório dos Índios of 1757 suppressed many traditional customs and promoted the secularization of missions following the expulsion of the Jesuits, yet it prohibited enslavement and recognized Indigenous peoples as subjects of the Crown. This law enabled the first lawsuits filed by Indigenous groups against the state, many of which were successful.[20][24] In 1755, another law extended the indigenato to all Brazilian Indigenous peoples,[47] but its regulation was delayed until 1850 and never fully enforced.[48]

Meanwhile, obstacles continued to multiply. A Royal Charter of 1798, while granting citizenship status to "civilized" Indigenous peoples, relegated them to vassals and declared those still in the forests as orphans under state tutelage, subject to forced labor at any time.[19] Despite several Portuguese attempts to ban Indigenous slavery, which sometimes sparked revolts among the white population, the practice persisted, particularly in remote and impoverished regions.[20] Another Royal Charter in 1801 allowed the conquest of new Indigenous lands through so-called "fair wars," aimed at forcibly subjugating resistant peoples, converting their territories into unclaimed lands.[24][35] By the end of colonization, the Indigenous population had plummeted to an estimated 600,000, most living in conditions of oppression and poverty.[19]

In the Empire, the situation did not improve. Although Indigenous peoples were increasingly valued in official discourse as the archetypal founders of the nation—pure peoples living in harmony with nature, to the extent that emperors wore ceremonial cloaks adorned with toucan feathers to symbolize their inclusion in a new national unity, and some Romantic intellectuals and artists, the Indianists, even mythologized them—[49][50][51] they were not mentioned in the Constitution of 1824,[47] were still deemed legally incompetent, and remained subject to state efforts to catechize and civilize them.[27] They continued to face death, enslavement, and exploitation,[19] and were often confined to small areas around their villages, insufficient for their subsistence.[24] In some cases, villages were abolished by decree under the pretext that their inhabitants were already part of the Brazilian population.[19] In 1850, the Land Law was passed, the first to regulate private property in Brazil,[24] reaffirming Indigenous territorial rights through the indigenato.[47] However, other laws allowed settlers to claim traditional lands as vacant through simple declaration, facilitating the fraudulent appropriation of Indigenous territories, known as land grabbing.[24] Furthermore, in imperial colonization projects involving foreigners, such as Germans and Italians, companies often hired gunmen to "clear" Indigenous peoples from areas designated for settlement.[19][52]

Upon the Republic's establishment, positivists showed great interest in Indigenous peoples, viewing them as true nations with rights to self-determination. Despite the influence of Positivism on national politics at the time,[19] the first Republican Constitution of 1891 again omitted mention of Indigenous peoples and failed to recognize their territorial rights.[24] Some state constitutions, however, granted limited territorial protections.[19] Under this Constitution, unclaimed lands, previously managed by the Union, were transferred to the states. As many Indigenous lands fell under this category, this created opportunities for further land grabbing, including in border areas originally excluded from such transfers for national security reasons. The federal government only demarcated Indigenous lands after agreements with state and municipal authorities, exacerbating confinement policies. Unable to sustain themselves in their small reserves, many Indigenous peoples were forced to seek livelihoods among non-Indigenous populations, working as low-skilled, poorly treated laborers in construction or agriculture, with no protections or guarantees.[24]

In the early 20th century, influential figures like Hermann von Ihering, director of the Museu Paulista, advocated for the extermination of Indigenous peoples who resisted civilization. However, in 1907, Brazil faced international condemnation for massacring its Indigenous populations, a factor that led to the creation of the Indian Protection Service in 1910, initially led by Marshal Cândido Rondon, himself of Indigenous descent and a staunch defender of their rights and dignity.[19][27] Rondon stated, "Indians should not be treated as state property within whose borders their territories lie, but as autonomous nations with whom we seek to establish friendly relations."[53] The Service secured some traditional lands for their original inhabitants, protected them from invasions, and, to some extent, recognized the value of their cultures and institutions. Nevertheless, the 1916 Brazilian Civil Code reaffirmed Indigenous peoples as legally incompetent, subjecting them to tutelage until deemed assimilated into civilization. In practice, the Service’s activities, while preventing many imminent massacres, focused on pacifying uncontacted groups, acculturating them, and turning them into small-scale farmers.[19][27]

Addressing the omission of the Constitution of 1891, the Constitution of 1934 and subsequent constitutions recognized Indigenous rights to the lands they traditionally occupied.[54] From the 1940s on, interest in Indigenous issues grew among anthropologists, sociologists, ethnologists, historians, environmentalists, and philosophers. Figures like Darcy Ribeiro and the Villas-Bôas brothers significantly increased their visibility and respect, reporting their oppression and abandonment while highlighting the richness and originality of their cultures.[19][25][27] By this time, however, the Indigenous population had dwindled to approximately 120,000 and continued to decline.[19] In 1961, the Xingu National Park was established, a vast conservation area home to many native peoples. It broke with prior paradigms by prioritizing their right to preserve their cultures in their entirety, free from Western influence, within the natural environment necessary for their traditions to endure.[24][25]

During the military regime (1964–1984), further protections were introduced, such as Constitutional Amendment No. 1/69, which designated Indigenous lands as Union property, mitigating some immediate threats of dispossession. It also recognized Indigenous peoples’ exclusive usufruct rights to natural resources on their lands, their right to judicial representation, and declared null any acts threatening their land possession, invalidating claims of acquired rights by others. These measures sparked controversy, seen as threats to private property, at a time when the Indian Protection Service struggled with ineffectiveness and faced accusations of irregularities, omission, and corruption. The Service was abolished in 1967, replaced by the National Indigenous People Foundation (FUNAI). In response to criticism, the government pledged greater attention to native peoples, leading to the creation of the Indian Statute.[24][55]

On the other hand, the military regime placed the Amazon at the center of developmentalist policies. Previously largely untouched by civilization, it was now seen as vital for national integration under the doctrine of national security. Many villages were displaced for colonization, forestry, and agriculture projects, or for infrastructure developments like roads, power lines, and dams. Both private entities and the state were authorized to exploit natural resources on Indigenous lands on a large scale.[24][55] Amid this upheaval, many previously isolated or semi-isolated peoples came into closer contact with outsiders, leading to conflicts and, above all, new epidemics that decimated many communities.[28] Under such pressure, this period saw the rise of Indigenous political awareness, with communities seeking recognition, respect, and empowerment. They began organizing into associations and self-initiated movements, connecting with trade unions, quilombo communities, peasant leagues, and the landless movement, all of which shared similar demands.[16][17]

The Indian Statute

[edit]

The Indian Statute (Law 6 001), enacted in 1973, remains in effect today. Despite extensive debate, conflicts with the latest Constitution, and a proposed bill to amend it, the reform has never been voted on.[56] The Statute defined the legal status of Indigenous peoples and their communities, aiming to "preserve their culture and integrate them, progressively and harmoniously, into the national community." It considered Indigenous peoples integrated when they were "incorporated into the national community and recognized as fully exercising civil rights, even while retaining customs, traditions, and practices characteristic of their culture."[57]

The law categorized lands into three types: Traditionally Occupied Lands, Reserved Lands, and Lands Owned by Indigenous Peoples. Traditionally Occupied Lands (Indigenous areas) were defined in the Constitutions of 1967 and 1969. Reserved Lands are areas designated by the Union for Indigenous usufruct, not necessarily their traditional territories, ensuring compensation to landowners in cases of expropriation. Lands Owned by Indigenous Peoples are those acquired through purchase or adverse possession.[57][58]

According to the Statute, reserved areas include the following modalities:

- Indigenous Reserve, as described above;

- Indigenous Agricultural Colony, intended for mixed occupation by acculturated Indigenous peoples and non-Indigenous individuals, aiming to reconcile conflicts between Indigenous land claims and the interests of non-Indigenous occupants;

- Federal Indigenous Territory, an administrative unit under the Union with at least one-third Indigenous population, a modality never implemented;

- Indigenous Park, inspired by the Xingu National Park, defined as "an area within land possessed by Indigenous peoples," associated with environmental preservation.

The Statute also declared null and void any legal effects of "acts of any nature concerning the ownership, possession, or occupation of lands inhabited by Indigenous peoples or communities." However, it reserved the Brazilian state’s right to intervene in these lands in specific cases, such as "for national security imperatives," "for public works in the interest of national development," or "for the exploitation of subsurface resources of significant importance to national security and development." The definitions of "national security" and "significant importance," and their judicious application, have been highly controversial ever since.[15][27][57][59][60][61] According to Luciana Alves de Lima,

- "For the first time, Indigenous peoples were protected by specific legislation. However, while this law aims to protect Indigenous culture, it places greater emphasis on integrating Indigenous peoples into the national community. The Indian Statute, in its Article 4, classifies Indigenous peoples as isolated, in the process of integration, or integrated. Isolated Indigenous peoples are those with no or minimal contact with non-Indigenous populations. Those in the process of integration live in 'intermittent or permanent contact with outsiders, retaining a lesser or greater degree of their native lifestyle, but adopting some practices and ways of life common to the broader national community, increasingly relying on these for their sustenance.' Integrated Indigenous peoples are those 'incorporated into the national community and recognized as fully exercising civil rights, even while retaining customs, traditions, and practices characteristic of their culture.' The law also regulates, across its 68 articles, issues concerning land rights, cultural heritage, bilingual education, healthcare, criminal provisions, and the assets and income of Indigenous heritage."[27]

The application of the Statute, despite the significant advances it introduced, proved extremely complex and unproductive, hindered by extensive bureaucracy. In 1988, a higher legal framework emerged that, by embracing multiculturalism, conflicted with some of the Statute’s core assumptions: a new Constitution. This Constitution, in turn, faced similar challenges in implementation and regulation regarding Indigenous peoples.[16][27]

The Constitution of 1988 and Other Provisions

[edit]

In addition to declaring in 5th Article that "all are equal before the law, without distinction of any kind," the Constitution of 1988 reaffirmed (for the third time) the principle of indigenato, establishing Indigenous peoples as the first and natural owners of the land. This inherent and primary right precedes all others, meaning their entitlement to their land does not require formal recognition.[15][25][62][48][63] This right was reinstated because the Constituent Assembly broke with the prior assumption that Indigenous cultures were destined to be assimilated and homogenized into Brazilian culture. Instead, it recognized their intrinsic value and the essential role of traditional lands in preserving these cultures intact, as expressed in Chapter VIII, "On Indigenous Peoples": "Lands traditionally occupied by Indigenous peoples are those permanently inhabited by them, used for their productive activities, essential for preserving the environmental resources necessary for their well-being, and required for their physical and cultural reproduction, according to their customs, traditions, and practices." The Constitution also nullified any acts aimed at occupying, owning, or possessing these lands, except in cases of "significant public interest of the Union."[64]

The Constitution further guaranteed the right of Indigenous individuals, communities, and organizations to represent themselves in court to defend their rights and interests, with the Public Prosecutor’s Office mediating all proceedings.[64] With the approval of the new Brazilian Civil Code in 2002, Indigenous peoples were removed from their status as wards, granting them greater legal autonomy, subject to special regulation.[65] However, this regulation has not progressed.[58] Although Indigenous peoples hold "exclusive usufruct of the riches of the soil, rivers, and lakes" on their lands, these lands remain Union property. The Congress must authorize resource exploitation by others, per complementary regulations and after consulting affected communities, who are entitled to a share of the proceeds.[25][62][64][65]

The Constitution set a five-year deadline for demarcating all Indigenous lands, but this was not fulfilled, leaving lands in different legal statuses.[62] According to several prominent jurists, including members of the Supreme Federal Court, the Constitution is not retroactive, invalidating claims to lands not effectively occupied by Indigenous peoples at the time of its promulgation. This view, along with disputes over other aspects, has significantly complicated the definitive transfer of traditional lands to Indigenous peoples.[16][27][66] Conversely, the Constitution dedicated an entire chapter to the natural environment, with significant implications for Indigenous lands, now recognized as treasures of biodiversity and sources of invaluable environmental services for all.[25] In recent years, several legal provisions have addressed Indigenous interests in areas such as health, environment, education, archaeological and intangible heritage, social assistance, production support, and land regularization.[67]

Meanwhile, the dire situation of Indigenous peoples worldwide was debated in international forums, leading to the creation of organizations and commissions to address and help resolve their issues. Broad initiatives by the United Nations and its affiliates, such as the International Labour Organization and UNESCO, resulted in international conventions and standards governing relations between civilized societies and Indigenous peoples, seeking to ensure mutual rights harmoniously while particularly protecting Indigenous peoples due to their vulnerable and historically oppressed condition.[16][27][68] The Convention No. 169, adopted at the 76th International Labour Conference and ratified by Congress on 20 June 2002, guaranteed Indigenous peoples more specific rights regarding the protection of their cultures, advocating for multiculturalism. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples of 2007 is another landmark, reaffirming their rights to an autonomous, safe, and fulfilling life, emphasizing the need for "free, prior, and informed consent" for the use of their lands by others, and recognizing informal Indigenous institutions governing community life, as well as intellectual property rights. The document also highlighted the tragic history of persecution, oppression, and extermination of these peoples, their role in nature conservation, and the urgent need for understanding and good relations between Indigenous and other societal groups.[27][68] UNESCO, for its part, approved the Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions in 2005, including Indigenous cultures among its priorities,[69][70] and established the International Day of the World's Indigenous Peoples, aiming to raise global awareness.[68]

Organization of the Indigenous Movement and Overview of the Current Scenario

[edit]

Meanwhile, the awareness and organization of Brazilian Indigenous peoples grew stronger, seeking greater autonomy from a government stance perceived as paternalistic and welfare-driven, increasingly seen as more harmful than beneficial. Leaders such as Marçal de Souza, Ailton Krenak, Mário Juruna, Marcos Terena, and Raoni began gaining national and international recognition. They connected with other social movements but remained largely uncoordinated among themselves.[71][72][73][74][75] To address this, during the Free Land Camp of 2005, the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB) was established, uniting many regional associations to consolidate demands and unify the Indigenous movement’s agenda.[73] The APIB gained credibility and representativeness, becoming a prominent advocate for Indigenous rights in Brazil. One of its most notable actions was participating in the Peoples’ Summit (Cúpola dos Povos), held in Rio de Janeiro in 2012 alongside the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development.[76] According to political scientist Bruno Lima Rocha, the APIB "elevates the status of this struggle, as by fostering self-representation, it surpasses the condition of tutelage and indirect delegation through entities like the Indigenous Missionary Council and the ongoing contradictions within the National Indian Foundation."[73]

Churches, academics, NGOs, and various social sectors in recent decades have devoted attention to Brazilian Indigenous peoples, providing significant support for many of their land-related demands.[77] In 2006, after intense pressure, the government approved the creation of the National Indigenous Policy Commission, subordinate to FUNAI, to "assist in intersectoral government coordination and promote greater Indigenous participation and social oversight of government actions."[59]

However, as discussed below, despite this legal, institutional, and moral support, the challenge remains far from resolved. The effective support Indigenous peoples receive from society as a whole has been insufficient to secure their legally guaranteed rights, leading to widespread abuses.[60][61][78] The stance of the Indigenous Missionary Council, a respected Catholic organization advocating for Indigenous rights and affiliated with the Episcopal Conference of Brazil, summarises the main criticisms:

- "The extermination of Indigenous peoples continues through the confinement of communities to insufficient lands; the government’s delays in land demarcation processes; neglect in healthcare and education; the public authorities’ inaction against daily aggressions; the invasion of lands by loggers, land grabbers, and ranchers; and the systematic violence against Indigenous peoples. These threats to their lives are no less severe than those faced in other periods of our history."[78]

Demarcation process

[edit]

Land possession is the primary demand of Brazilian Indigenous peoples. The purpose of demarcation is to materially secure their right to land.[79] The process was first established in a 1973 law commonly known as Estatuto do Índio and has been revised several times, most recently in 1996.[80][81]

The Indian Statute specified that all Indigenous lands should be demarcated by 1978,[82] and the 1988 Constitution also set a five-year deadline.[2] However, demarcation is still ongoing. The process is frequently delayed by legal disputes arising from the objections of non-indigenous settlers and commercial interests in the proposed TI. This has been increasingly common since 1996, when a change in the law required an explicit period to be set aside in the demarcation process for the hearing of complaints.[4] In 2008 the Supreme Federal Court issued a high-profile decision in favour of the continued territorial integrity of Raposa Serra do Sol in Roraima. Settlers had protested their deportation from the TI, arguing that the reserve undermined Brazil's national integrity and the state's economic development, and proposing that it be broken up. The ruling established a legal precedent that affected more than 100 similar cases that were before the Supreme Court at the time.[6][10]

The demarcation process follows a systematic procedure, as outlined in Article 19 of the Indian Statute and regulated by the Executive Branch.[17][80] The current procedure is stipulated by Decree 1.775 of January 1996 and consists of the following stages:

- Identification Studies: An anthropological study is conducted by an anthropologist recognized as competent by FUNAI to identify the Indigenous land within a set timeframe. Subsequently, a specialized technical group, coordinated by an anthropologist and preferably composed of Funai technicians, conducts complementary studies. This group performs sociological, legal, cartographic, environmental, and land tenure analyses to define the boundaries of the Indigenous land. The report submitted to Funai must include the data specified in Portaria nº 14 of 9 January 1996.[17][80]

- Funai Approval: The report is presented for Funai’s review. If approved by Funai’s president, a summary of the report is published in the Diário Oficial da União (Official Federal Gazette) and the Official Gazette of the state where the lands are located, within fifteen days. The summary must also be posted at the local municipal office.[17][80]

- Contestation Period: Any interested party may contest the recognition of the Indigenous land from the start of the process until 90 days after the summary’s publication in the Diário Oficial. Contesters submit their reasons and relevant evidence to Funai. Contestation may aim to identify flaws in the report or demand compensation. After the contestation period ends, Funai has 60 days to prepare opinions on the contestations and forward them to the Ministry of Justice.[17][80]

- Delimitation: The Minister of Justice has 30 days to issue a resolution, which may: declare the area’s boundaries and order its physical demarcation; prescribe additional measures to be completed within another 90 days; or disapprove the identification, publishing a reasoned decision based on Paragraph 1 of Article 231 of the Constiution.[17][80]

- Physical Demarcation: If the boundaries are declared, FUNAI is responsible for the physical demarcation. The INCRA handles the resettlement of any non-Indigenous population occupying the area.[17][80]

- Homologation: The President of the Republic is responsible for the homologation of the Indigenous land.[17][80]

- Registration: After homologation, the land must be registered within 30 days at the property registry office of the district where it is located and with the Union’s Heritage Service.[17][80]

Even after this process, the lands require further regularization to address issues such as the presence of squatters or unauthorized resource exploitation. Additional measures are necessary to ensure the preservation of Indigenous cultures, social identity, and the full citizenship of their individuals.[17]

Area and Population

[edit]

The total area of Indigenous lands is constantly changing, with many lands involved in legal disputes or still in the identification and delimitation phases. In 2006, these lands covered 125,545,870 hectares.[83] By 2009, there were 611 areas spanning 105,672,003 hectares, divided into delimited lands (33; 1.66%), declared lands (30; 7.67%), homologated lands (27; 3.40%), and regularized lands (398; 87.27%), including 123 lands under study with areas yet to be researched and defined.[84]

As of 2016[update], there were 702 Indigenous territories in Brazil, covering 1,172,995 km2 – 14% of the country's land area.[85] As of 2020, 120 areas were in the formal process of being identified, covering a total of 1,084,049 hectares; 43 had been formally identified (2,179,316 ha); 74 had been formally declared (7,305,639 ha) and 487 had already been formally approved (106,858,319 ha).[7] In total, 723 areas were either under evaluation or had been legally consolidated as Indigenous territories, covering a total area of 117,427,323 hectares.[7]

According to Funai, in 2017, there were 115 records of isolated peoples in the Legal Amazon, with 28 confirmed and 86 still under investigation.[86] There are also groups seeking recognition of their Indigenous status to secure their lands.[87][77][59] For historical reasons —Portuguese colonisation started from the coast— 98% of the country's Indigenous lands are located in the Legal Amazon, comprising over 400 areas and occupying approximately 21% of the Amazon.[8] The remainder is distributed across other regions. There are only two federated units without any TIs: the state of Rio Grande do Norte and the Federal District.[88]

Population counts in Brazil, regarding ethnicity, rely on self-declaration. The 2022 IBGE census recorded 1,694,836 people identifying as Indigenous, with 914,746 living in urban areas and 780,090 in rural areas.[9] Of Brazil’s 5,570 municipalities, only 737 have no self-declared Indigenous population.[9] However, figures from the national census can be misleading. According to the Instituto Socioambiental, pilot tests for the 2010 census revealed cases where Indigenous individuals misunderstood the questions and identified as mixed-race or Asian.[89] They are divided into 279 ethnic groups, accounting for about 0.83% of the country’s total population.[9][90] The North region has the highest proportion, with 753,780 people being Indigenous.[91][92][93] With an original population in the 16th century estimated at 2 to 5 million, possibly more, after a steady decline until the 1980s, the Indigenous population is now growing, though some ethnic groups are not following this trend and are nearing extinction. Seven groups had fewer than 40 members at the time of the 2010 survey. Historically, many have already gone extinct.[92][89][94]

Indigenous territories by state (2022)

[edit]| Flag | State | Number of TIs [95][tn 1] |

Proportion of state area [96][tn 2] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acre | 36 | 15.68% | |

| Alagoas | 13 | 0.99% | |

| Amapá | 6 | 8.36% | |

| Amazonas | 176 | 29.37% | |

| Bahia | 31 | 0.57% | |

| Ceará | 10 | 0.14% | |

| Distrito Federal | 0 | 0% | |

| Espírito Santo | 3 | 0.40% | |

| Goiás | 7 | 0.11% | |

| Maranhão | 23 | 7.44% | |

| Mato Grosso | 89 | 16.72% | |

| Mato Grosso do Sul | 66 | 2.52% | |

| Minas Gerais | 18 | 0.23% | |

| Pará | 68 | 25.17% | |

| Paraíba | 4 | 0.60% | |

| Paraná | 32 | 0.63% | |

| Pernambuco | 18 | 2.10% | |

| Piauí | 3 | 0.01% | |

| Rio de Janeiro | 6 | 0.11% | |

| Rio Grande do Norte | 0 | 0% | |

| Rio Grande do Sul | 61 | 0.40% | |

| Rondônia | 30 | 21.13% | |

| Roraima | 35 | 46.42% | |

| Santa Catarina | 29 | 1.03% | |

| São Paulo | 35 | 0.30% | |

| Sergipe | 2 | 0.20% | |

| Tocantins | 13 | 9.36% | |

| Brazil | 805 | 13% |

Conflicts and controversies

[edit]Criticism

[edit]

Land ownership is a contentious issue in Brazil. In the 1990s, as much as 45% of the available farmland in the country was controlled by 1% of the population.[97] Some advocates of land reform have therefore criticised the amount of land reserved for Indigenous peoples, who make up just 0.2% of the national population. According to this view the 1988 Constitution's approach towards Indigenous peoples' right to land is overly idealist, and a return to a more integrationist policy is favoured.[12] In the Raposa Serra do Sol dispute, settlers and their advocates charged TIs with hindering economic development in sparsely populated states such as Roraima, where a large proportion of the land is reserved for Indigenous peoples despite commercial pressures to develop it for agricultural use.[11] Instituto Socioambiental, a Brazilian Indigenous rights group, argue that the disparity between Indigenous population and land ownership is justified because their traditional subsistence patterns (typically shifting cultivation or hunting and gathering) are more land extensive than modern agriculture, and because many TIs include large areas of agriculturally unproductive land or are environmentally degraded due to recent incursions.[8]

Opponents of Indigenous territories also claim that they undermine national sovereignty. The promotion of Indigenous rights by NGOs is seen as reflecting an "internationalisation of the Amazon" which is contrary to Brazil's economic interests.[10][11] Elements in the military have also expressed concern that because many TIs occupy border regions they pose a threat to national security – although both the army and police are allowed full access.[6]

The current system of Indigenous territories has also been criticised by proponents of Indigenous rights, who say that the process of demarcation is too slow[4] and that FUNAI lacks the resources to properly protect them from encroachment once registered.[98]

Public Policies and Legislation

[edit]The Brazilian government is responsible for ensuring the legal rights of Indigenous peoples. Several ministries, such as Justice and Environment, are directly involved, with FUNAI overseeing the implementation of public policies for Indigenous peoples, supported by various other entities and societal participation.[99] Its budget grew from 100 million reais in 2006 to 423.1 million in 2010. Many new staff were appointed, salaries increased, the role of Indigenous specialist was recognized, and in recent years, Funai has undertaken numerous activities. Notable examples include the creation of the National Indigenous Policy Commission, the development of the Agenda for Indigenous Peoples and Indigenous Citizenship Territories, and a draft for a new Statute of Indigenous Peoples, alongside the establishment of dozens of new reserves.[100]

Also noteworthy is the creation of the National Policy for Environmental and Territorial Management of Indigenous Lands, which aims to develop "integrated and participatory strategies for sustainable development and Indigenous autonomy."[99][101] It includes training Indigenous and non-Indigenous managers to work cooperatively, sustainable land management plans, and support for Indigenous peoples during demarcations and environmental licensing processes for resource exploitation.[99][101] In 2013, its Management Committee was established, with participation from government and community representatives.[102]

Until 2013, the government sought partnerships with society and the international community to better manage the complex issue of Indigenous territories, implementing numerous interconnected programs, including protection against violence, international cooperation, land regularization, scientific research, awareness campaigns, promotion of quality of life, healthcare, support for productive activities, preservation of historical heritage, archaeological sites, and intangible heritage, poverty reduction, general education, and technical training.[101][102][103][104][105][106][107]

Possession of their traditional lands is fundamental for Indigenous peoples. These lands are considered sacred, holding the graves of their ancestors, the origins of their myths, and sustaining their culture and way of life, which define each people’s unique identity.[17][19][27][78][108] The equality of Indigenous peoples with other peoples, their right to self-determination, and their right to preserve their lands and cultures are internationally recognized and enshrined in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples,[109] of which Brazil is a signatory.[110]

Despite this and constitutional provisions, the demarcation of Indigenous lands in Brazil has been a chronic issue with widespread social repercussions. According to numerous Indigenous organizations, as well as many supporters and prominent figures in science, education, law, religion, and other fields, the government’s recent Indigenous policies are unfair, undignified, and scandalous, systematically undermining Indigenous rights in Congress and other official bodies that are obligated to uphold their constitutional protections. This reinforces the discriminatory, negligent, and exploitative treatment Indigenous peoples have faced since colonial times.[59][60][61][78][111][112][113][114][115][116][117][118][119][120][121][122][123]

Among the laws considered serious threats to Indigenous survival and cultural integrity is Portaria 303/12, published under pressure from the ruralist caucus to authorize government projects on Indigenous lands without prior consultation, as required by the Constitution, citing the Union’s significant interest.[115][124][125][126] In 2012, Maria Luiza Grabner, Regional Federal Prosecutor in São Paulo, stated that irregular cases are already numerous: "This is one of the biggest complaints from Indigenous peoples. Projects are happening, and laws are being passed without real consultation. Often, what occurs is mere communication, informing that the project will proceed, without building an agreement."[114] According to anthropologist Manuela Carneiro da Cunha, one of Brazil’s most respected scholars on Indigenous issues, "the government is sacrificing Indigenous rights," launching "an unprecedented offensive in Congress against Indigenous peoples. [...] The president seems increasingly hostage to the PMDB and agribusiness, allied with evangelicals. This bloc fiercely opposes demarcation and eviction (removal of invaders) from Indigenous areas."[60] She continues:

- "Colonial legislation and all Brazilian constitutions have always recognized Indigenous rights to their lands. But one thing is the principle, another one its application. In the classic fable, the wolf finds successive justifications to devour the lamb. [...] We are witnessing a remake of past Brazil, as if the 20th century never existed. We’ve returned to exporting commodities, exploiting resources without regard for human and environmental costs. And we’ve returned to the tactics of the 16th and 17th centuries: the principle is affirmed, but exceptions are created to render it meaningless. This is what Law 227/2012 attempts: it defines the Union’s significant interest so broadly that Indigenous constitutional guarantees become a dead letter."[60]

On 16 April 2013, frustrated with PEC 215, which transferred demarcation powers to Congress, hundreds of Indigenous people invaded the Chamber of Deputies’ plenary session.[127] After two years waiting to meet with the Presidency, on 18 April, over 700 leaders representing 121 Indigenous peoples expressed their indignation:

- "We protest because our relatives are being murdered, because our lands are not demarcated. We requested an audience with Dilma, but the most they offered was a meeting with Minister Gilberto Carvalho and other ministers on Friday, 19 April, Indigenous Peoples’ Day, so the government could have a photo for its propaganda, showing concern for Indigenous issues. No, we no longer want to talk to those who solve nothing! Two years ago, during the 2011 Free Land Camp, we Indigenous peoples submitted a list of demands to these ministers, and nothing was addressed. Since then, we’ve lost count of how many times Dilma has met with landowners, construction companies, miners, and hydroelectric groups. She issued decrees and ordinances to benefit them, while barely demarcating or homologating our traditional lands. She allowed her congressional base to hand key committees to ruralists and their allies."[117]

President Dilma later met with the Indigenous leaders, stating that Brazil is a country where laws are upheld and promising to advance the regulation of ILO Convention 169, which requires prior consent for projects on Indigenous lands. However, she advocated for a negotiated solution to conflicts, considering that other sectors besides Indigenous peoples must be heard.[128][129][130][131] Sônia Guajajara, an Indigenous representative, called the meeting with Dilma "historic" for fulfilling a long-standing desire and opening dialogue. However, she rejected the Presidency’s decision to alter consultation processes for demarcations and infrastructure projects on Indigenous lands "without free, prior, and informed consent." They demanded active participation in all processes, the repeal of harmful legal instruments, and other measures to prevent what they described as the "planned extinction" of their peoples orchestrated by the government.[132]

Despite some progress in recent decades, resulting in population growth and increased land area for Indigenous peoples,[83] recent government programs have sparked widespread controversy and significant setbacks.[15][27][59][60][133] During the Bolsonaro administration, the legal situation of Indigenous peoples worsened further. According to Marcos Pereira Rufino:

- "The federal government’s actions under Jair Bolsonaro’s administration regarding Indigenous policy are marked by strong antagonism toward Indigenous territorial rights, enshrined in the 1988 Constitution, and toward public policies for these populations established over the past three decades of civilian governments. As president, Jair Bolsonaro worked to fulfill his campaign promise not to demarcate any Indigenous lands during his term, avoiding the creation of territories that, in his words, could become ‘new countries in the future.’ Beyond obstructing new demarcations and various initiatives attacking rights enshrined in the Constitution, the president and other members of his government made hostile and inappropriate statements about the country’s Indigenous peoples, expressing a mix of anger, fear, indignation, and apprehension, reproducing a discursive structure long present in the rhetoric of political and economic groups that supported him in the 2018 election, such as those tied to agribusiness, mining, and logging."[134]

During his term, 795 Indigenous people were killed, according to the Indigenous Missionary Council’s report, which cited land invasions, neglect or denial of healthcare, reduced funding for protective agencies, racism, threats, and physical and sexual violence as structural causes contributing to Indigenous extermination.[135] A dossier by FUNAI’s staff association Indigenistas Associados (INA) and the Institute of Socioeconomic Studies stated that FUNAI was dismantled and disstructured, noting that "under Bolsonaro’s government, the National Indian Foundation (FUNAI) has implemented a policy that can be called anti-Indigenous. [...] Funai is a glaring example of the destruction of policies activated at the federal level in Brazil during the 2019–2022 governmental cycle. The internal erosion of Indigenous policy aligns with that of environmental, cultural, and racial policies, which various researchers have shown, through concepts like authoritarian infralegalism or institutional harassment, to be the modus operandi of Bolsonaro’s government."[136] According to Bruna Bronowski, "Bolsonaro’s government did not demarcate a single centimeter of Indigenous land in Brazil, as promised before taking office. Its Indigenous policy is considered ‘genocidal’ and promotes the ‘normalization’ of Indigenous deaths."[135]

A recent positive development for Indigenous peoples was the 2023 Supreme Federal Court ruling against the milestone thesis for land demarcation, which required proof of occupation in 1988, the year the Constitution was promulgated. However, this victory did not solve the issue entirely,[137] and the ruralist caucus vowed to respond. According to Evair de Mello, vice-president of the Agricultural Parliamentary Front, "we will need to take some procedural steps. [...] We can obstruct the government’s agenda, propose a new bill, and take it to the plenary. From Parliament’s perspective, anything is possible."[138] The ruralist caucus holds a congressional majority and, fulfilling their promise, in October, Congress urgently passed Law 14.701, amending the Constitution to authorize the milestone thesis. The Public Prosecutor’s Office deemed the law unconstitutional and contrary to international treaties signed by Brazil, and President Lula vetoed its main points.[139][140] On 14 November, Congress overturned the presidential veto on most vetoed points by a wide margin, also removing several protections for Indigenous lands: it banned the expansion of already demarcated lands, authorized military and Federal Police activities and the installation of military bases without prior community consultation, and permitted highway expansion, electricity exploitation, and the safeguarding of natural resources deemed strategically important, also without prior consultation.[141] The Ministry of Native People announced it would engage the Attorney General’s Office to file an unconstitutionality action with the Supreme Federal Court.[142] According to BBC reporter Leandro Prazeres, "the clash between the government and ruralists is far from over."[143]

Development Pressures

[edit]

Opposition to Indigenous interests is significant among various societal sectors, particularly those tied to economic development, which wield substantial capital and political influence.[61][78][116][117][144][145] Agribusiness faces the most accusations from Indigenous advocates and is one of the most influential sectors shaping Brazil’s political and economic direction. Its strength lies in its significant share of exports: in 2019, it accounted for 43% of total exports, generating annual revenues above 90 billion dollars since 2011.[146][147] Most ruralist complaints argue that Indigenous peoples are few and their lands too vast, taking space that could be used for crops or cattle grazing, posing a threat to food security and the economy.[148][149][116] However, this claim lacks solid grounding, as assessments by Embrapa technicians and a joint statement by the Brazilian Society for the Advancement of Science and the Brazilian Academy of Sciences assert that Brazil does not lack land; what is needed is better utilization.[149][150] It is estimated that Brazil has 340 million hectares of arable land, half of which are pastures, with at least 100 million hectares of pastures underutilized.[151][152][153] According to the Indigenous Missionary Council (CIMI):

- "The ruralist caucus attacks Indigenous peoples’ rights through various instruments in the Chamber of Deputies and Senate. Over a hundred legislative proposals contrary to Indigenous rights are under consideration in both houses. Among them are Constitutional Amendment Proposals (PECs) 215/2000, 038/1999, and 237/2013. Indigenous peoples know that ruralists aim to use PEC 215/2000 today as they did with the Forest Code in 2012: to weaken Indigenous rights and gain control to prevent land demarcations. [...] Demarcations stalled by the federal government and ruralists attacking to block new demarcations, review existing ones, and exploit demarcated lands—this is what Indigenous peoples see in Brazil’s Indigenous policy landscape. It is against this synchronized attack by the federal government and agribusiness that Indigenous peoples react to preserve and enforce their rights, in legitimate defense of their existence as individuals and peoples."[61]

Other economic sectors are also influential. Mining is a major source of disputes.[59][123][154] According to the Constitution, "mineral prospecting and extraction on Indigenous lands can only proceed with Congressional authorization, after consulting affected communities, with their guaranteed share in the results, as provided by law." However, this matter remains unregulated. All mining in the form of small-scale mining by non-Indigenous people is prohibited on Indigenous lands, yet illegal miners are common. For example, the Cinta Larga lands were invaded by 5,000 miners, speculators, smugglers, and organized groups after discoveries of diamonds, cassiterite, and other minerals.[155] An April 2013 Instituto Socioambiental study highlighted mining pressures: "There are 152 Indigenous lands in the Amazon potentially threatened by mining projects. All mining processes on Indigenous lands are suspended, but if released, they would cover 37.6% of these areas." The controversial Law 1.610 under consideration in Congress seeks to enable this. According to Raul Silva Telles do Vale from Instituto Socioambiental, Indigenous lands are far more valuable as generators of environmental services than as fields for extracting finite natural resources.[156] Mining’s environmental impacts include pollution and siltation of rivers, land transformation, and deforestation, alongside social impacts from Indigenous contact with outsiders.[155] According to Melissa Curi, a University of Brasília professor and FUNAI employee:

- "Close contact between mineral exploiters and Indigenous communities always results in fatal harm to the Indigenous peoples, mainly due to the aggressive and immediate lifestyle of the former. Beyond violence, highly contagious and dangerous diseases are transmitted, such as venereal diseases, tuberculosis, malaria, etc., [...] and the introduction of dominant society values, like fascination with money and what it can buy. With these new habits, what is observed over time is the deterioration of tribal life, followed by the loss of social identity and assimilation into the dominant society, i.e., the transition from an autonomous society to a dependent minority."[155]

Hydroelectric projects, which have multiplied in recent years, are another major source of conflict.[59][112][118] The Coordination of the Indigenous Organizations of the Brazilian Amazon issued an open letter condemning the government’s policy of investing in mega-energy projects that harm Indigenous peoples, traditional communities, and the environment, with questionable technical efficiency.[118] The construction of the Belo Monte Dam became the most notorious example, surrounded by significant violence and ongoing controversy. Reports of human rights violations reached the Organization of American States, which requested explanations from the Presidency and a halt to construction. The request was ignored, and in retaliation, Brazil recalled its ambassador to the organization and threatened to withhold funding.[157][158][159][160]

Institutional Crisis and Human Rights

[edit]The relationship between Indigenous peoples and the Brazilian government has been chronically and notoriously tense. In a 2013 official statement, the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB) clarified that "the so-called 'participatory process,' with regard to the country's Indigenous peoples and organizations, has strictly not occurred, despite a few isolated and informal meetings with some peoples and communities. [...] The General Secretariat of the Presidency [...] has sought to discredit the organizations of the Indigenous movement, fostering internal division and weakening not only the movement but also the official Indigenous agency, Funai, contrary to our peoples' and organizations' aspirations for strengthening the institution."[161]

The Brazilian judiciary has been inconsistent in its rulings, often prolonging demarcation processes for decades, further complicating the issue.[24][25][162][111][163] The regularization of Pataxó lands, for example, took nearly a century to resolve. It is estimated that at least 90% of demarcation processes face legal challenges.[60] The Public Prosecutor's Office has been accused of acting as a puppet of international NGOs,[164] and other government departments face similar corruption allegations.[162][165] FUNAI itself has been criticized by ruralists and even the government. It has been accused of fostering a "land demarcation industry," facilitating the "import" of Indigenous people from Paraguay to organize invasions, and fraudulently identifying communities as Indigenous to create nonexistent "traditional" lands, in a confrontational and deceptive policy allegedly encouraged by CIMI, the Instituto Socioambiental, NGOs, and other entities.[28][166][167][168][169][170][171][172] Even many Indigenous people view FUNAI as having lost credibility, describing it as either dilapidated, outdated, incompetent, or staffed with corrupt officials who sometimes override dissenting leaders and communities or co-opt others with bribes.[165][173][174][175] In 2013, the government intervened in FUNAI, stripping it of its exclusive authority over demarcations and redistributing some of its responsibilities to other agencies tied to social and economic development.[169][176][177]

During the Bolsonaro administration, Indigenous policy faced further setbacks. Funai was significantly weakened, and its actions have been heavily criticized by Indigenous advocates and environmentalists, who accuse it of serving interests harmful to Indigenous peoples, primarily driven by business and evangelical groups. Numerous technical positions were filled by unqualified individuals, its budget was drastically cut, Indigenous lands faced legal threats, new demarcations were halted, invasions by land grabbers, loggers, ranchers, and mining companies surged by 150% since his election, and violent conflicts escalated.[178][179][180] According to Márcio Santilli of the Instituto Socioambiental, "FUNAI has been turned upside down: the current Indigenous policy promotes political isolation and division among Indigenous peoples to facilitate the plunder of their lands' natural resources."[179] In January 2020, several major Indigenous organizations issued a manifesto stating that "the threats and hate speech of the current government are promoting violence against Indigenous peoples, the murder of our leaders, and the invasion of our lands."[178] The recent situation has drawn international attention, sparking protests abroad. Fiona Watson, research director at Survival International, noted, "We continue to receive dozens of reports from across Brazil about what appears to be an open war against Indigenous communities." Sydney Possuelo, a former FUNAI director and Indigenous rights advocate, said, "The situation of Brazil’s Indigenous peoples has never been good. But in 42 years working in the Amazon, this is the most dangerous moment I’ve ever seen." David Karai Popygua, a Guarani spokesperson, declared, "It’s as if we are now a target of the government to be eliminated."[181] Bolsonaro also proposed a bill to allow mining in reserves, sparking further protests. According to Carlos Rittl, executive secretary of the Climate Observatory, "the anti-environmental agenda continues and started 2020 with great voracity. Claiming it will bring benefits to Indigenous lands, it will keep fueling conflict, increase deforestation, river pollution, mercury contamination, and heighten threats of violence against Indigenous peoples and local Amazon communities."[180]

There are also allegations that some Indigenous individuals, including chiefs, criminally favor the exploitation of their own peoples and lands by accepting bribes and personal benefits, pressuring public authorities, sometimes in collusion with Funai officials and police, leading to frequent violence and suffering, as well as further setbacks in building productive dialogue based on trust, honesty, and goodwill.[165][164][175][182][183][184] However, such cases are rare in the broader context. According to a statement by the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil, "It must be said: the majority of Indigenous peoples and communities in Brazil do not share the aspirations of a minority of individuals who are swayed and misled by the disguised ill intentions of this government."[185]

The conflicts sparked by these disputes have escalated to armed struggles. Numerous violent clashes have occurred between Indigenous peoples and private and public security forces, miners, contractors, farmers, and other armed groups, resulting in many deaths.[59][165][186][187][188][189] In 2012, violence against Indigenous peoples surged by 237% compared to 2011, typically linked to land demarcation disputes. According to CIMI, 563 Indigenous people were murdered in the country over the past decade.[190] CIMI’s 2018 report noted ongoing violence, with 110 murders, 847 cases of omission and delays in land regularization, 20 territorial rights conflicts, 96 cases of land invasions, illegal resource exploitation, and property damage, and 59 cases of timber and mineral theft, illegal hunting and fishing, soil and water contamination by pesticides, and arson, among other crimes. Indigenous suicides reached 128.[191] The 2019 CIMI report recorded 277 cases of violence against Indigenous peoples, with 113 resulting in death. Land invasions rose from 109 in 2018 to 825 in 2019.[192] These grievances, documented globally, have led to complaints at international forums like the International Labour Organization and the United Nations, which have questioned the government about reported irregularities and crimes, demanding explanations and corrective measures.[119][120][122][193][194] In November 2019, the Human Rights Advocacy Collective and the Arns Commission filed a complaint with the International Criminal Court accusing Jair Bolsonaro of "crimes against humanity" and "incitement to genocide against Brazil’s Indigenous peoples." In July 2020, the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil filed a complaint with the Supreme Federal Court, arguing that institutionalized racism exists and that "a genocide is underway."[195] Among the most concerning recent conflicts are those involving the Guarani-Kaiowá and Cinta Larga, the demarcation of the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous Territory, the transfer of the São Francisco River, and the construction of the Belo Monte Dam, which have affected dozens of peoples.[59][165]

Security

[edit]High-ranking military officials have also expressed concerns, viewing Indigenous lands as potential threats to national security, which could pose another challenge to Indigenous interests.[28][162][110] The presence and activities of the Brazilian Federal Police and military agencies on Indigenous lands are regulated by law, granting them freedom of movement and access, ensuring the establishment and maintenance of military and police units, and supporting programs and projects for border control and protection.[163][196][197][198] While legislation ensures defense agencies’ access to Indigenous lands, their operations often lead to conflicts with Indigenous communities, particularly in international border areas. Some military officials argue that reserves along borders are vulnerable to invasion and could serve as bases for international organized crime.[110][163][199][200] Additional arguments come from General Luiz Eduardo Rocha Paiva, whose controversial views are shared by some peers, according to certain scholars:[28][162][165]

- "Reserves became a problem for national sovereignty after Brazil ratified, in 2007, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The document established, among other principles, that Indigenous peoples have the right to self-governance, political self-determination, their own political institutions and legal systems, to belong to an Indigenous nation, to veto military activities on their lands, and to accept or reject legislative measures by the Union. Military, legislative, or administrative actions by the State on Indigenous territory must be previously consented to by Indigenous peoples. If this actually happens, we will fragment the Federation, because there are more Indigenous lands than states in the Federation. And I note that if there is land, a people considered a nation, and their own political and legal institutions, that is a Nation-State. That’s where the threat lies."[110]

Nelson Jobim, former president of the Supreme Federal Court, as well as former Minister of Defense and Justice, argues that national security concerns do not apply to Indigenous land demarcation. He believes the discord stems from a misunderstanding of the law, as the debate should focus on the possession and usufruct of land, not its ownership, since, under the Constitution, all Indigenous lands are inalienable Union property.[201]

Culture and Environment

[edit]

Awareness among Indigenous peoples is growing daily. Many are studying at universities to better defend their peoples’ rights, gaining support from numerous international organizations and influential figures. Their mobilizations and public protests now attract significant societal attention.[24][25][111][163] However, despite recent studies indicating increased political influence of Indigenous peoples across the continent, this has not translated into improved public policies directed toward them.[59][203] Nor has it prevented ongoing murders and abuses, with many still living in poverty without assigned territories or in invaded or undersized reserves, creating significant pressures that disrupt communities and traditions. Often, they are forced to migrate to cities, facing even worse conditions, joining the masses in favelas of large urban centers and losing touch with their cultural roots.[24][25][27][59][111][163][204][205][206][207]

Given delays in demarcation and the rapid expansion of the agricultural frontier, the idea of substitute Indigenous reserves outside traditionally inhabited areas has resurfaced as a way to resolve conflicts with squatters or farmers, which often lead to lengthy legal disputes. However, this solution faces resistance from Indigenous peoples and advocates, who view it as a setback to their right to lands they have inhabited for centuries and to which they are deeply connected.[24] Since the 1980s, complex issues have also emerged regarding the transmission of Indigenous traditions by Indigenous teachers trained in Western models and teaching within reserves, how Indigenous land issues are presented to Brazilian schoolchildren by non-Indigenous teachers, and how the Western world is perceived by reserved Indigenous peoples. These questions fundamentally probe the quality of information exchanged between the two worlds. This early information must be accurate, as it can either reinforce or dismantle myths and prejudices critical to future dialogue between generations.[208][209][210][211][212] In 2001, over 90,000 Indigenous students were enrolled in formal schools within reserves, supported by the government and communities. The 2012 National Curriculum Guidelines for Indigenous Education aim for all teachers in villages to be Indigenous.[209]

Beyond issues of invasions and unconsulted uses, which fragment many Indigenous lands with roads, bridges, railways, power lines, dams, mining, squatters, and other invasive interference, others are progressively isolated within a heavily altered surrounding environment, suffering impacts from environmental degradation in neighboring areas, such as invasive species, aquifer depletion, wildfires, and soil and water contamination by pesticides used on adjacent farms, indirectly threatening their sustainability even if the reserves themselves remain well-preserved.[213][214] Reserves in the South, Northeast, and Southeast, all small in size, are the most affected, but even vast areas like the Xingu Park face such impacts.[215][216]

Resolving the Indigenous land issue will have significant effects for these peoples, enabling the survival of their unique cultures, which are deeply tied to their natural environment, and for forest conservation, given the extensive deforestation in Brazil and numerous threats to biodiversity and ecosystems, ultimately benefiting society at large.[25][27][118][217] Indeed, many of these communities are considered models of sustainable forest management, and the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, one of the most comprehensive scientific syntheses on the environment in recent decades, stated that Indigenous peoples can be as effective at forest preservation as conventional protected reserves.[218]

However, defining how Indigenous peoples should utilize their lands’ resources, to which they have constitutional rights, remains contentious. Even within the Indigenous movement, there is uncertainty. Some advocate that Indigenous peoples should act as environmental guardians, keeping the land untouched and adhering to traditional subsistence practices, while others support sustainable management in Western models, including commercial production and capital accumulation—a right guaranteed to all Brazilians but subject to a different legal framework, raising the potential for new conflicts from the outset.[25][214]

Growing proximity to civilization has profoundly altered traditional cultures. Many Indigenous people now prefer urban life, forming urban villages, drawn by opportunities for education, employment, healthcare, recognition, and perceived conveniences. However, this migration typically exposes them to risks, leaving them among the most vulnerable social groups. Contact with civilization brings dramatic challenges, including alcoholism, drug addiction, prostitution, the spread of sexually transmitted diseases, suicide among youth, and domestic violence.[203][204][205][206][207][219] In the 2010 census, about 42% of those who identified as Indigenous lived outside Indigenous lands, with roughly 78% of them in cities. Of all Indigenous people over five years old, only 37.4% spoke their ethnic group’s language.[220] Many still feel ashamed of their Indigenous identity. However, many urbanized groups value their roots and strive to preserve them in this challenging environment, raising new questions about what it means to be Indigenous in the 21st century.[206][207][221][222] According to anthropologist Lúcia Helena Rangel, a professor at PUC-SP, "Brazilian elites do not want to recognize Indigenous rights and create tensions between the population and communities, fostering a racist discourse, especially toward Indigenous people living in cities." She adds:

- "The underlying issue is land. However, we cannot reduce everything to this question. But many problems stem from it, because when a land is not recognized, Indigenous people lack access to healthcare, educational programs, agricultural inputs, food projects, etc. So, it’s a land issue, a dispute over Indigenous lands, and a failure to recognize Indigenous rights to their lands [...] Moreover, some say certain Indigenous people are no longer Indigenous because they have curly hair, live in cities, or are ‘mixed,’ meaning they have fewer rights than others. In a mestizo country like ours, where everyone is mixed, Indigenous people cannot be mixed. At times, they are deemed too Indigenous and a nuisance; at others, they are not Indigenous enough and have no rights. So, Indigenous people never have a place."[56]

The portal Indigenous Peoples in Brazil, maintained by the Instituto Socioambiental, offers an assessment of the current situation of Indigenous peoples and their lands: