Madison Square and Madison Square Park

Snow-covered Madison Square Park at night, looking south (December 2005) | |

Location within Manhattan | |

| Namesake | James Madison |

|---|---|

| Maintained by | Government of New York City |

| Location | New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 40°44′32″N 73°59′17″W / 40.74222°N 73.98806°W |

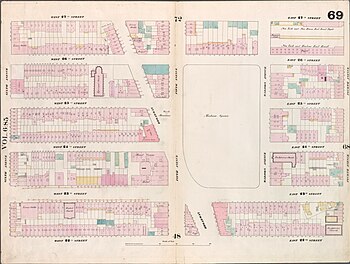

| North | 26th Street |

| East | Madison Avenue |

| South | 23rd Street |

| West | Fifth Avenue and Broadway |

| Other | |

| Website | Madison Square Park |

Madison Square is a public square formed by the intersection of Fifth Avenue and Broadway at 23rd Street in the New York City borough of Manhattan. The square was named for Founding Father James Madison, the fourth president of the United States. The focus of the square is Madison Square Park, a 6.2-acre (2.5-hectare) public park, which is bounded on the east by Madison Avenue (which starts at the park's southeast corner at 23rd Street); on the south by 23rd Street; on the north by 26th Street; and on the west by Fifth Avenue and Broadway as they cross.

The park and the square are at the northern (uptown) end of the Flatiron District neighborhood of Manhattan. The neighborhood to the north and west of the park is NoMad ("NOrth of MADison Square Park") and to the north and east is Rose Hill.

Madison Square is probably best known around the world for providing the name of a sports arena called Madison Square Garden. The original arena and its successor were located just northeast of the park for 47 years, until 1925. The current Madison Square Garden, the fourth such building, is not in the area. Notable buildings around Madison Square include the Flatiron Building, the Toy Center, the New York Life Building (built on the site of the first two arenas), the New York Merchandise Mart, the Appellate Division Courthouse, the Met Life Tower, and One Madison, a 50-story condominium tower.

Early history of the area

[edit]

The area where Madison Square is now had been a swampy hunting ground crossed by Cedar Creek – which was later renamed Madison Creek – from east to west,[2] and first came into use as a public space in 1686. It was used as a potter's field in the 1700s.[3] In 1807, "The Parade", a tract of about 240 acres (97 ha) from 23rd to 34th Streets and Third to Seventh Avenues, was designated for use as an arsenal, a barracks, and a drilling area.[4] There was a United States Army arsenal there from 1811 until 1825 when it became the New York House of Refuge for the Society for the Protection of Juvenile Delinquents, for children under sixteen committed by the courts for indefinite periods. In 1839 the building was destroyed by fire.[5][6][7] The size of the tract was reduced in 1814 to 90 acres (36 ha), and it received its current name.[4]

In 1839, a farmhouse located at what is now Fifth Avenue and 23rd Street was turned into a roadhouse under the direction of William "Corporal" Thompson (1807–1872), who later renamed it "Madison Cottage", after the former president.[8] The roadhouse was the last stop for people traveling northward out of the city, or the first stop for those arriving from the north; visitors were encouraged not to sleep more than five to a bed.[2] Though Madison Cottage itself was razed in 1852,[8][2] it ultimately gave rise to the names for the adjacent avenue (Madison Avenue) and park, which are therefore only indirectly named after President James Madison.[8]

The roots of the New York Knickerbocker Base Ball Club, one of the first organized baseball teams, are in Madison Square. Amateur players began in 1842 to use a vacant sandlot at 27th and Madison for their games and, eventually, Alexander Cartwright suggested they draw up rules for the game and start an organized team. When they lost their sandlot to development, they moved across the Hudson River to Hoboken, New Jersey, where they played their first game in 1846.[5][7][2]

Opening of the park

[edit]On May 10, 1847, the 6.2-acre (2.5 ha)[9] Madison Square Park, named after President James Madison,[5] opened to the public.[4] Within a few years, the tide of residential development, which was relentlessly moving uptown, had reached the Madison Square area. Initially, the houses around the park were narrow, crowded and dark brownstone rowhouses with small rooms easily subject to becoming cluttered. Today, the only remnant of these brownstones is a single building at 14 East 23rd Street.[2]

Despite this beginning, through the 1870s, the neighborhood became an aristocratic one of brownstone row houses and mansions where the elite of the city lived; Theodore Roosevelt, Edith Wharton and Winston Churchill's mother, Jennie Jerome, were all born here.[4][5]

Madison Cottage was torn down in 1852 to make way for Franconi's Hippodrome, which lasted only for two years. It was an arena which seated 10,000 customers, and presented chariot races on its 40-foot (12 m) wide track, as well as exotic animals such as elephants and camels. A money-loser, it would be razed so that the Fifth Avenue Hotel could be built on the site.[2]

In 1853, plans had been made to build the Crystal Palace there, but strong public opposition and protests caused the palace to be relocated by the Board of Aldermen to the site of present-day Bryant Park.[10]

During the 1863 New York City draft riots, 10,000 Federal troops brought in to control the rioters encamped in Madison Square and Washington Square, as well as Stuyvesant Square.[7] Madison Square was also the site in November 1864 of a political rally, complete with torchlight parade and fireworks, in support of the presidential candidacy of Democrat General George B. McClellan, who was running against his old boss, Abraham Lincoln. It was larger than the Republican parade the night before, which had marched from Madison Square to Union Square to rally there.[7]

Commercialization of the neighborhood

[edit]The Fifth Avenue Hotel, a luxury hotel built by developer Amos Eno, and initially known as "Eno's Folly" because it was so far away from the hotel district, stood on the west side of Madison Square from 1859 to 1908.[11] It was the first hotel in the nation with elevators, which were steam powered and known as the "vertical railroad", which had the effect of making the upper floors more desirable as they no longer had to be reached by climbing stairs.[12] It had fireplaces in every bedroom, private bathrooms, and public rooms which saw many elegant events. Notable visitors to the hotel included Mark Twain, Swedish singer Jenny Lind, railroad tycoon Jay Gould, financier "Big Jim" Fisk, the Prince of Wales and U.S. Presidents James Buchanan, Abraham Lincoln, Andrew Johnson, Ulysses S. Grant, Rutherford B. Hayes, James A. Garfield, Chester A. Arthur, Grover Cleveland, Benjamin Harrison and William McKinley. Theodore Roosevelt's campaign headquarters for his unsuccessful campaign for mayor in 1886, and his likewise failed campaign for governor in 1898 were located in the hotel.[2] The hotel, which was noted for its "Amen Corner" where Republican political boss Thomas Collier Platt held court in the 1890s,[2][13][14] was closed and demolished in 1908.[15] It is reported that patrons of the hotel's bar spent $7.000 on drinks on its last day of operation.[2] A plaque on the Toy Center, the building currently on the site, commemorates the hotel.[5]

With the success of the Fifth Avenue Hotel, which could house 800 guests, other grand hotels such as the Hoffman House, the Brunswick and the Victoria, opened in the surrounding area, as did entertainment venues such as the Madison Square Theatre and Chickering Hall.[6] Upscale restaurants such a Delmonico's and high-end retail shops opened up along Fifth Avenue and Broadway, in addition, nearby exclusive private clubs such as the Union, Athenaeum and Lotos clubs, began to open. But also, "concert-saloons", like "The Luovre", full of waitresses in provocative short skirts who served drinks and provided music-hall entertainment for the customers, began to appear as well; the waitresses were often willing to take the male customers upstairs to private rooms, or to one of the many nearby brothels which had also started to pop up.[2]

With the center of the expanding city moving north by the turn of the century, and the neighborhood becoming commercialized, elite residents moved farther uptown, away from Madison Square, enabling more restaurants, theatres and clubs to open up in the neighborhood, creating an entertainment district, albeit an upscale one where society balls and banquets were held in restaurants such as Delmonico's. Nearby, huge dry-goods emporia such as Siegel-Cooper in the Ladies' Mile district brought daytime crowds of shoppers.[16] No longer primarily residential, Madison Square was still a thriving area.

Worth Square

[edit]At the western side of Madison Square Park, on an island bordered by Broadway, Fifth Avenue, and 25th Street, stands an obelisk, designed by James Goodwin Batterson[17] which was erected in 1857 over the tomb of General William Jenkins Worth, who served in the Seminole Wars and the Mexican War,[5] and for whom Fort Worth, Texas, was named, as well as Worth Street in lower Manhattan.[18] The city's Parks Department designated the area immediately around the monument as a parklet called General Worth Square.[19]

Renewal

[edit]

Madison Square Park lost some acreage in 1870 when the west side was reduced so that Broadway could be widened and parking provided for hansom cabs,[2] but it was also re-landscaped by William Grant and Ignatz Pilat,[17] a former assistant to Frederick Law Olmsted. The current park maintains their overall design.[2]

New features

[edit]The new design brought in the sculptures that now reside in the park. One notable sculpture is the seated bronze portrait of Secretary of State William H. Seward, by Randolph Rogers (1876), which sits at the southwest entrance to the park. Seward, who is best remembered for purchasing Alaska ("Seward's Folly") from Russia, was the first New Yorker to have a monument erected in his honor.[20]

Other statues in the park depict Roscoe Conkling, who served in Congress in both the House and the Senate, and who collapsed at that spot in the park while walking home from his office during the Blizzard of 1888 and died five weeks later, after refusing to pay a cab $50 for the ride;[21][22] Chester Alan Arthur, the 21st President of the United States; and David Farragut, who is supposed to have said "Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead" in the Battle of Mobile Bay during the Civil War. The Farragut Memorial (1881), which was first erected at Fifth Avenue and 26th Street and moved to the Square's northern end in 1935,[23] was designed by Augustus Saint-Gaudens (sculpture) and architect Stanford White (base).[24]

Along the south edge of the park is the Eternal Light Flagstaff, dedicated on Armistice Day 1923 and restored in 2002, which commemorates the return of American soldiers and sailors from World War I.[25]

Another park highlight is the granite Southern Fountain, a modern reproduction of the original fountain, which was first located on the site of the Old Post Office. It was completed in 1843, before being rededicated in the park in 1867.[26] The modern replacement was installed in 1990, and renovated in 2015.[27][28]

Jemmy's Dog Run is located beside the park's entrance from West 25th Street.[29] It was expanded in 2022.[30]

Innovation and fashionability

[edit]Madison Square continued to be a focus of public activities for the city. In the 1870s, developer Amos Eno's Cumberland apartment building, which stood on 22nd Street where the Flatiron Building would eventually be built, had four-stories of its back wall facing Madison Square, so Eno rented it out to advertisers, including the New York Times, who installed a sign made up of electric lights. Eno later put a canvas screen on the wall, and projected images on it from a magic lantern on top of one of his smaller buildings on the lot, presenting both advertisements and interesting pictures in alternation. Both the Times and the New York Tribune began using the screen for news bulletins, and on election nights crowds of tens of thousands of people would gather in Madison Square, waiting for the latest results.[31]

In 1876, a large celebration was held in Madison Square Park to honor the centennial of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Then, from 1876 to 1882, the torch and arm of the Statue of Liberty were exhibited in the park in an effort to raise funds for building the pedestal of the statue.[32]

Madison Square was the site of some of the first electric street lighting in the city. In 1879, the city authorized the Brush Electric Light Company to build a generating station at 25th Street, powered by steam, that provided electricity for a series of arc lights which were installed on Broadway between Union Square (at 14th Street) and Madison Square. The lights were illuminated on December 20, 1880. A year later, 160-foot (49 m) "sun towers" with clusters of arc lights were erected in Union and Madison Squares.[7]

The area around Madison Square continued to be commercially fashionable, if not residentially. In 1883, art dealer Thomas Kirby and two others established a salon "for the Encouragement and Promotion of American art" on the south side of the Square. Their American Art Association auction rooms, the first auction house in the US, quickly became the place to go in New York to buy and sell jewelry, antiquities, fine art and rare books.[33]

Madison Square Garden

[edit]

The building that became the first Madison Square Garden at 26th Street and Madison Avenue was built in 1832 as the passenger depot of the New York and Harlem Rail Road,[34] and was later used by the New York and New Haven Railroad as well; both were owned by Cornelius Vanderbilt.[35] When the depot moved uptown in 1871 to Grand Central Depot, the building stood vacant until 1873, when it was leased to P. T. Barnum[34] who converted it into the open-air "Monster Classical and Geological Hippodrome" for circus performances, exhibits transferred from Barnum's American Museum, as well as cowboys and "Indians", tattooed men, bicycle races, dog shows, and horse shows.[2]

In 1875 the Garden was sub-let to the noted band leader Patrick Sarsfield Gilmore, who filled the space with trees, flowers and fountains and named it "Gilmore's Concert Garden". Gilmore's band of 100 musicians played 150 consecutive concerts there, and continued to perform in the Garden for two years. After he gave up his sub-let, others presented marathon races, temperance and revival meetings, balls, the first Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show (1877), as well as boxing "exhibitions" or "illustrated lectures", since competitive boxing matches were illegal at the time. It was finally renamed "Madison Square Garden" in 1879 by William Kissam Vanderbilt, the son of Commodore Vanderbilt, who continued to present sporting events, the National Horse Show, and more boxing, including bouts by John L. Sullivan that drew huge crowds. Vanderbilt eventually sold what Harper's Weekly called his "patched-up grimy, drafty combustible, old shell" to a syndicate that included J. P. Morgan, Andrew Carnegie, James Stillman and W. W. Astor.[7][36]

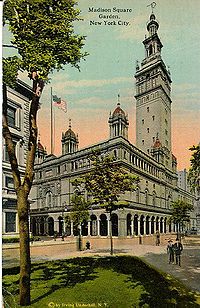

The building that replaced it was a Beaux-Arts structure designed by the noted architect Stanford White. White kept an apartment in the building, and was shot dead in the Garden's rooftop restaurant by millionaire Harry K. Thaw over an affair White had with Thaw's wife, the well-known actress Evelyn Nesbit, who White seduced when she was 16. The resulting sensational press coverage of the scandal caused Thaw's trial to be one of the first Trials of the Century.

Madison Square became known as "Diana's little wooded park" after the huge bronze statue of the Roman goddess Diana by Augustus Saint-Gaudens that stood atop the 32-story tower of White's arena; at the time it was the second-tallest building in the city.

The Garden hosted the annual French Ball, both the Barnum and the Ringling Brothers circuses, orchestral performances, light operas and romantic comedies, and the 1924 Democratic National Convention, which nominated John W. Davis after 103 ballots, but it was never a financial success.[7] It was torn down soon after, and the venue moved uptown. Today, the arena retains its name, even though it is no longer located in the area of Madison Square.

Ceremonial arches

[edit]

To celebrate the centennial of George Washington's first inauguration, in 1889 two temporary arches were erected over Fifth Avenue and 23rd and 26th Streets. Just ten years later, in 1899, the Dewey Arch was built over Fifth Avenue and 24th Street at Madison Square for the parade in honor of Admiral George Dewey, celebrating his victory in the Battle of Manila Bay in the Philippines the year before. The arch was intended to be temporary, but remained in place until 1901 when efforts to have the arch rebuilt in stone failed, and it was demolished.

Fifteen years passed, and in 1918 Mayor John F. Hylan had a Victory Arch built at about the same location to honor the city's war dead. Thomas Hastings designed a triple arch which cost $80,000 and was modeled after the Arch of Constantine in Rome. Once again, a bid to make the arch permanent failed.[37]

20th century

[edit]Early century

[edit]The park was the site of an unusual public protest in 1901. Oscar Spate, a displaced Londoner, convinced the Parks Commissioner, George Clausen, to allow him to pay the city $500 a year to put 200 cushioned rocking chairs in Madison Square Park, Union Square, and Central Park and charge the public 5 cents for their use. Free benches were moved away from shaded areas, and Spate's chairs replaced them. When a heat wave hit the city in July, people in Madison Park refused to pay the nickel that was now required to sit in the shade. The police became involved, and newspapers like The Sun and William Randolph Hearst's Evening Journal took up the cause. People began going to the park with the intent of sitting and refusing to pay, and a riot occurred involving a thousand men and boys, who chased the chairs' attendant out of the park and overturned and broke up chairs and benches.[38][39] The police were called, but the disturbance nevertheless continued for several days. On July 11, Clausen annulled the city's 5-year contract with Spate (whose real name was Reginald Seymour), prompting a celebration with bands and fireworks in Madison Square Park attended by 10,000 people. Spate went to court and got a preliminary injunction against Clausen's breaking of the contract, but the judge refused to allow him to force the public to pay. The Evening Journal followed by asking for an injunction against pay chairs, and when this was granted Spate gave up. He sold the chairs to Wanamaker's, where they were advertised as "Historic Chairs".[39]

Two months later, in September, the Seventy-first Regiment Band played "Nearer, My God, to Thee" in the park as recognition of the death by assassination of President William McKinley. The hymn had been McKinley's favorite.[40]

On the election night of November 4, 1902, a fireworks disaster led to the deaths of 15 people (Including Patrolman Dennis Shea of the NYPD) and the wounding of 70, as a display meant to celebrate the election of William Randolph Hearst to Congress misfired.[41]

In 1908, the New York Herald installed a giant searchlight among the girders of the Metropolitan Life Tower to signal election results. A northward beam signaled a win for the Republican candidate, and a southward beam for the Democrat. The beam went north, signaling the victory of Republican William Howard Taft.

America's first community Christmas tree was illuminated in Madison Square Park on December 24, 1912, an event which is commemorated by the illuminated Star of Hope on a tall pole, installed in 1916 at the southern end of the park.[42] Today the Madison Square Park Conservancy continues to present an annual tree-lighting ceremony sponsored by local businesses.

Author Willa Cather described Madison Square around 1915 in her novel My Mortal Enemy (1926):

Madison Square was then at the parting of the ways; had a double personality, half commercial, half social, with shops to the south and residences to the north. It seemed to me so neat, after the raggedness of our Western cities; so protected by good manners and courtesy—like an open-air drawing-room. I could well imagine a winter dancing party being given there, or a reception for some distinguished European visitor.[43]

A commercial neighborhood

[edit]In the early part of the 20th century, the neighborhood around Madison Square Garden became known for the number of clothing manufacturers who had set up shop there, as well as industrial concerns such as the Lionel Train Company, which had its headquarters there, where it displayed its first model train layout. Lionel's competitor, the A. C. Gilbert Company, set up its New York "Hall of Science" in the neighborhood as well, in 1941, on 25th Street across from Worth Square, in a building that still stands, addressed as 202 Fifth Avenue; Gilbert also displayed its train layouts. Lionel eventually bought up Gilbert in 1967.[2]

The toy industry gravitated to the area during World War I, with a number of toy manufacturers having locations at 200 Fifth Avenue – where the Fifth Avenue Hotel once stood – and which eventually became the International Toy Center. In 1967, the center expanded up Broadway to an additional building at 1107 Broadway, and the two were connected by a pedestrian bridge. The Toy Center was for many years the site of the annual New York Toy Fair until 2005, when the center closed. Some of the major manufacturers, such as Mattel and Hasbro, expanded out of the Toy Center building into their own headquarters nearby, Mattel on West 23rd Street and Hasbro on Sixth Avenue.[2]

Mid-century

[edit]In 1936, to commemorate the centennial of the opening of Madison Avenue, the Fifth Avenue Association donated an oak from Montpelier, the Virginia estate of former president James Madison. It is located toward the center of the eastern perimeter of the park.

The New York City Department of Traffic announced a plan in 1964 to build a parking garage underneath the park, much like the Boston Common, Union Square in San Francisco and MacArthur Park in Los Angeles. The plan was successfully blocked by preservationists, who cited concerns about the damage that the excavation would cause to the park, particularly the roots of its many trees.[44][45]

On October 17, 1966, a fire at 7 East 23rd Street resulted in one of the deadliest building collapses in the history of the New York City Fire Department, when 12 FDNY staff—two chiefs, two lieutenants, and eight firefighters—were killed. This was the department's greatest loss of life before the September 11 terrorist attacks.[46] A plaque honoring the victims can be seen on Madison Green, the apartment building currently occupying the site.[47]

Restoration

[edit]By the middle of the 20th century, some of the buildings in the neighborhood were half-empty,[2] and it was widely recognized that the park needed to be restored and renovated.[48] Efforts began in 1979 with a privately funded program to clean up and maintain the park, the first time that non-public funding was used in New York City for long-term work in the city's parks.[48] Then, in November 1986, ground was broken on what was to become the full-scale restoration of the park. Phase one of the project, involving the north end of the park and Worth Square, was completed in 1988, and included the addition of a playground in the northeast corner. Phase two was to have begun in November 1987, but never got started, leaving the south end of the park unrestored for 11 years.[48]

In 1997, the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation asked the City Parks Foundation to organize an effort to raise funds to complete the revitalization. Their "Campaign for the New Madison Square Park" led to the renovation and restoration of the park, the addition of a dog run and the return of 1,200 square feet (110 m2) to the southeast corner.[48] An outgrowth of the fund-raising campaign was the formation of Madison Square Park Conservancy,[49] a public-private partnership whose mission is to keep it "a bright, beautiful and active public park."[50]

One amenity, added to the park in July 2004, is the Shake Shack, a popular permanent stand that serves hamburgers, hot dogs, shakes and other similar food, as well as wine. Its distinctive building, which was designed by Sculpture in the Environment, an architectural and environmental design firm based in Lower Manhattan, sits near the southeast entrance to the park.[51] In 2010, park designer and horticulturalist Lynden Miller was hired to reconfigure the planting beds.[52]

Current status

[edit]The names of the neighborhoods around Madison Square have changed frequently, and continue to do so. Around the park and to the south is the Flatiron District, an area that, since the 1980s, has changed from a primarily commercial district with many photographer's studios—located there because of the relatively cheap rents—into a prime residential area. Rose Hill is to the north and east of the park, while NoMad is to the north and Chelsea is to the west. Within the area, Madison Avenue continues to be primarily a business district, while Broadway just north of the square holds many small "wholesale" and import shops. The area west of the square remains mostly commercial, but with many residential structures being built.

In 1989, the city's Landmarks Preservation Commission had created the Ladies' Mile Historic District to protect and preserve the area. Additionally, since 2001, the Madison Square North Historic District for the area north and west of the park,[53] in the neighborhood that since 1999 has been referred to as NoMad ("NOrth of MADison Square Park ").[54][55][56]

Buildings

[edit]

On the south end of Madison Square, southwest of the park, is the Flatiron Building, one of the oldest of the original New York skyscrapers, and just to east at 1 Madison Avenue is the Met Life Tower, built in 1909 and the tallest building in the world until 1913, when the Woolworth Building was completed.[57] As of 2020[update], the Met Life Tower contains a luxury hotel within its clock tower,[58] while the building's office space is being renovated.[59] The 700-foot (210 m) marble clock tower of this building dominates the park. The Met Life Tower absorbed the site of the architecturally distinguished 1854 building of the former Madison Square Presbyterian Church, designed by architect Richard Upjohn on the southeast corner of 24th Street, while the Metropolitan Life North Building replaced the 1906 replacement church on the northeast corner of 24th Street and Madison, designed by Stanford White and demolished in 1919.[60]

Nearby, on Madison Avenue between 26th and 27th Streets, on the site of the old Madison Square Garden, is the 40-floor, 615-foot (187 m) high New York Life Building, built in 1928 and designed by Cass Gilbert, with a square tower topped by a striking gilded pyramid.[61] Also of note is the statuary adorning the Appellate Division Courthouse of the New York State Supreme Court on Madison Avenue at 25th Street.[62]

To the west of the Flatiron Building, at the southwest corner of Fifth Avenue and 23rd Street, is Henry J. Hardenbergh's Western Union Telegraph Building, one of the first commercial buildings in the area. It was completed in 1884, the same year his Dakota Apartment Building was finished.[63]

Residential skyscrapers

[edit]One Madison, a 50-story residential condominium tower which opened in 2013, is located at 22 East 23rd Street, at the foot of Madison Avenue across from the park.[64][65] Down the block to the west, on the southeast corner of Broadway and 23rd Street, with the address of 5 East 22nd Street, is the Madison Green condominium apartment tower. While not architecturally notable, the building is significant as one of the first signs that the area was rebounding. The 31-story building was first announced in the mid-1970s, but was not constructed until 1982.[66][67] Near the other end of the 22nd Street block between Broadway and Park Avenue South is the Madison Square Park Tower at 45 East 22nd Street, a 64-story residential skyscraper which topped-out in 2017 and is expected to open in 2018.

Transportation

[edit]Madison Square can be reached on the New York City Subway via local service on the BMT Broadway Line (N, R, and W trains) at the 23rd Street station.[68][69] In addition, local stops on the IRT Lexington Avenue Line (6 and <6> trains) and IND Sixth Avenue Line (F, <F>, and M trains) are one block away at Park Avenue South and Sixth Avenue, respectively.[69][70]

Gallery

[edit]- In the past

-

Snowstorm, Madison Square

by Childe Hassam (c.1890).

Stanford White's Madison Square Garden

is in the background. -

Madison Square in 1893, looking north;

note the Worth Monument in the upper center -

Madison Square Park After the Rain

painted by Paul Cornoyer (c.1900) -

In 1920, the American artist Thomas Hart Benton depicted the Seward statue, the Eternal Light flagpole, and the Worth obelisk in his painting New York, Early Twenties.

-

A hand-colored postcard from the turn of the 20th century

- The park today

-

President Chester A. Arthur

-

The annual New York City Veterans Day Parade starts in the park and marches up Madison Avenue

-

Inside the park, April 2013

See also

[edit]- 10-minute walk

- 23 skidoo

- Flatiron Building

- Flatiron District

- Madison Square North Historic District

- Madison Square Park Fountain

- Met Life Tower

- NoMad

- Park conservancy

- Rose Hill, Manhattan

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ Federal Writers' Project (1939). New York City Guide. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-60354-055-1. (Reprinted by Scholarly Press, 1976; often referred to as WPA Guide to New York City.), p.207

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Blecher, George (August 3, 2018) "Murder, Politics and Architecture: The Making of Madison Square Park" Archived 2019-07-14 at the Wayback Machine The New York Times

- ^ "Walking Off the Big Apple: Madison Square Part 1" Archived 2011-07-14 at the Wayback Machine on the Manhattan User's Guide website. Accessed:2011-02-15

- ^ a b c d Mendelsohn (1998), p.13

- ^ a b c d e f Mendelsohn (1995)

- ^ a b Patterson

- ^ a b c d e f g Burrows & Wallace

- ^ a b c Shepard, Richard F. (February 4, 1977). "Broadway That Once Was". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 12, 2018. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

One tavern at the northwest corner of 23d Street and Broadway sported the name Corporal Thompson's Madison Cottage, in honor of President Madison and it gave its name to the park and later to the avenue that starts north nearby.

- ^ Event Horizon: Mad. Sq. Art.: Antony Gormley installation guide Archived 2020-04-11 at the Wayback Machine published by the Madison Square Park Conservancy

- ^ Chiu, Eric. "The New York Crystal Palace: The Birth of a Building", University of Maryland University Libraries. Accessed May 29, 2016. "The group of investors soon petitioned the Board of Aldermen in New York City for use of Madison Square, located in lower Manhattan where Broadway and Fifth Avenue meet at 23rd Street, to build a 'house of iron and steel for an Industrial Exhibition'. ... However, when the community around Madison Square learned of the project, there were many complaints that it would ruin the aesthetics of the neighborhood, and present a headache of construction and traffic up to and during the exhibition. The case was tried before the Chief Justices of New York City who ruled against the use of Madison Square, but the Board of Aldermen granted the investors the use of Reservoir Square, which was on 42nd Street between Fifth Avenue and what is currently the Avenue of the Americas, in its stead."

- ^ Madison Square North Historic District Designation Report Archived February 25, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, June 26, 2001. Accessed August 1, 2016.

- ^ Horsley, Carter B. "Fifth Avenue: The Best Address By Jerry E. Patterson" Archived 2021-05-19 at the Wayback Machine, The City Review. Accessed August 1, 2016. "It boasted a 'vertical railroad,' or elevator, the first installed in a hotel in the United States (though preceded by elevators in a few office buildings). ... The elevator was a great instrument of change in the perception of guests; in the past, rooms on the lower floors had been the most desirable because easier to reach. The upper floors were always cheaper; at the top and least desirable were the servants' rooms."

- ^ Miscione, Michael (December 18, 2004). "The Fifth Avenue Hotel". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 10, 2017. Retrieved August 11, 2018.

- ^ Adams, James Truslow ed. (1940) "Amen Corner" in Dictionary of American History. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons

- ^ Dailey, Jessica. "Remembering NYC's Grandest Forgotten Hotels, in Photos", Curbed New York, June 26, 2013. Accessed May 29, 2017. "The Fifth Avenue Hotel, built in 1859 at 200 Fifth Avenue, had the first passenger elevator ever installed in a U.S. hotel. ... It closed in 1908 and was immediately demolished to make way for the Toy Center Building."

- ^ Mendelsohn (1998), p.14

- ^ a b c White & Willensky

- ^ Moscow

- ^ "General Worth Square" Archived 2006-09-29 at the Wayback Machine on the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation website

- ^ Madison Square Park; William Henry Seward Archived 2024-09-30 at the Wayback Machine, New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. Accessed August 1, 2016. "This imposing bronze statue of statesman William Seward (1801–1872) was created by the artist Randolph Rogers (1825–1892). The sculpture was dedicated in 1876, and Seward is said to be the first New Yorker to be honored with a monument in the city."

- ^ "The Blizzard of 1888's Most Famous Victim: Roscoe Conkling" Archived 2024-09-30 at the Wayback Machine, Paul Rush New York Stories, January 11, 2009. Accessed February 15, 2011.

- ^ Madison Square Park: Roscoe Conkling Archived 2016-08-07 at the Wayback Machine, New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. Accessed August 1, 2016. "On March 12, 1888, while on his way to the New York Club at 25th Street, Conkling suffered severe exposure in Union Square, during the famous blizzard which gripped the city on that day. As a result, his health rapidly declined, and he died on April 18th, 1888."

- ^ Walsh, Kevin. Forgotten New York: Views of a Lost Metropolis, New York: Collins, 2006. p. 167. ISBN 0060754001

- ^ Madison Square Park: Admiral David Glasgow Farragut Archived 2016-08-07 at the Wayback Machine, New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. Accessed August 1, 2016. "The Admiral Farragut Monument at the north end of Madison Square Park is one of the finest outdoor monuments in New York City. Its creation was a collaboration of two of the finest artistic spirits of their age, sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens and architect Stanford White."

- ^ Barron, James (May 24, 2017). "Its Flagstaff Light Aglow Again, a Park Is Ready for Memorial Day". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 26, 2017. Retrieved May 29, 2017.

The light was first switched on in 1923 for Armistice Day, as the Nov. 11 holiday commemorating the end of World War I was then called.

- ^ "Madison Square Park: Madison Square Fountain". New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved January 12, 2016.

- ^ a b "Madison Square Renovation" Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine Delta Fountains

- ^ a b "Search: Fountain" Archived 2018-09-10 at the Wayback Machine Madison Square Park Conservancy. Quote: "The design of the Southern Fountain is based on the original Victorian fountain installed in the park in the 1860."

- ^ "Jemmy's Dog Run". Madison Square Park Conservancy. Archived from the original on December 30, 2023. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- ^ "Jemmy's Dog Run Now Open". Madison Square Park Conservancy. August 8, 2022. Archived from the original on December 30, 2023. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- ^ Alexiou, pp. 26-29

- ^ Margino, Megan. "The Arm That Clutched the Torch: The Statue of Liberty's Campaign for a Pedestal" Archived 2017-04-22 at the Wayback Machine, new York Public Library, April 7, 2015. Accessed May 29, 2016. "Six Years in Madison Square – With the wrist reaching treetops and rooftops, and the flame high enough to see for many blocks, the Arm of Liberty became a long-standing advertisement for the statue from 1876–1882. "

- ^ Burrows & Wallace, p.1081

- ^ a b Berman, p. 69

- ^ Burrows & Wallace, p.944

- ^ "Madison Square Garden I Archived 2013-06-17 at the Wayback Machine, Ballpark.com. Accessed May 29, 2017.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (September 4, 1994). "Readers' Questions; Gargoyles, the Guggenheim, Cantilevered Balconies". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 30, 2024. Retrieved July 31, 2010.

- ^ "Attendant Beaten By A Mob In Madison Square Park". New York Sun. July 7, 1901. Archived from the original on September 30, 2024. Retrieved August 1, 2016 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ^ a b Alexiou, pp.67-73

- ^ Alexiou, p.83

- ^ "15 KILLED, 70 HURT IN MADISON SQUARE; Explosion of Bomb Mortars Spreads Wide Disaster. IMMENSE CROWD IN PANIC Hundreds of Police and Scores of Doctors and Nurses Hurried to the Scene. 15 KILLED, 70 HURT IN MADISON SQUARE". The New York Times. November 5, 1902. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ^ "Madison Square Park: Star of Hope" Archived 2014-04-19 at the Wayback Machine on the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation website

- ^ Cather, Willa. My Mortal Enemy Archived 2009-10-25 at the Wayback Machine (1926) at Project Gutenberg of Australia

- ^ Silver, Nathan, Lost New York (1968) ISBN 0-618-05475-8

- ^ Alexiou, p.268

- ^ O'Donnell, Michelle (October 17, 2006). "Oct. 17, 1966, When 12 Firemen Died". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 14, 2016. Retrieved November 18, 2010.

- ^ Worth, Robert F. (October 12, 2003). "A Grievous Day, Eclipsed by Sept. 11; Some Never Forget Oct. 17, Once the Fire Department's Darkest Date". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 30, 2024. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

All that now remains at the site, a high-rise on East 23rd Street facing Madison Square Park, is a small bronze plaque with the date and the names of the dead.

- ^ a b c d Berman, pp.30-33

- ^ "Park History" Archived 2015-02-06 at the Wayback Machine on the Madison Square Park Conservancy website

- ^ "Mission" Archived 2014-10-30 at the Wayback Machine on the Madison Square Park Conservancy website

- ^ Staff (November 12, 2004). "The Listings". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 6, 2018. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

A cool new addition to Madison Square Park is the Shake Shack, a fast-food kiosk designed by the architecture firm Sculpture in the Environment (SITE) that was founded in 1970 by James Wines. It is partly a Postmodern hot dog stand, partly green architecture with its vegetation-covered roof and partly a way to generate revenue for the park.

- ^ "Gardener Steph: Plants of the Future". Madison Square Park. Archived from the original on February 25, 2020. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- ^ NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission "Madison Square North Historic District Designation Report" Archived March 11, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Louie, Elaine (August 5, 1999). "The Trendy Discover NoMad Land, And Move In". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 24, 2015. Retrieved July 31, 2010.

- ^ Feirstein, Sanna (2001). Naming New York: Manhattan Places & How They Got Their Names. New York: New York University Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-8147-2712-6.

- ^ Sternbergh, Adam (April 11, 2010). "Soho. Nolita. Dumbo. NoMad?". New York. Archived from the original on March 25, 2015. Retrieved July 31, 2010.

- ^ Staff (June 14, 1989). "Met Life Tower Named A New York Landmark". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 16, 2009. Retrieved November 18, 2010.

- ^ Alberts, Hana R. (May 28, 2015). "Tour the New York Edition Hotel, Carved From a Clocktower". Curbed NY. Archived from the original on November 8, 2019. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- ^ Matsuda, Akiko (November 16, 2020). "SL Green Gets $1.25B Construction Loan For One Madison Avenue". The Real Deal New York. Archived from the original on November 16, 2020. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ^ Staff (May 6, 1919). "Raze Parkhurst Church; Famous Piece of Architecture Making Way for Office Building". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 10, 2012. Retrieved November 18, 2010.

- ^ New York Life Insurance Company Building Archived 2016-12-26 at the Wayback Machine, New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, October 24, 2000. Accessed May 25, 2017.

- ^ Manhattan Appellate Court Archived 2017-10-29 at the Wayback Machine, New York City. Accessed May 25, 2017.

- ^ White & Willensky, pp.197-198

- ^ Ouroussoff, Nicolai (June 28, 2010). "Near-Empty Tower Still Holds Hope". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 6, 2020. Retrieved November 18, 2010.

- ^ Rubinstein, Dana (March 9, 2010). "In the Shadow of the Boom". The New York Observer. Archived from the original on March 13, 2010. Retrieved July 31, 2010.

- ^ Alexiou, pp. 268-269

- ^ "Madison Green - 5 East 22nd Street" Archived 2024-09-30 at the Wayback Machine on the City Realty website. Accessed:2011-02-17

- ^ "Manhattan Bus Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. July 2019. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ a b "About the Park" Archived 2016-01-05 at the Wayback Machine on the Madison Square Park Conservancy website

- ^ "Subway Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. September 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- ^ New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, p.190

Bibliography

- Alexiou, Alice Sparberg (2010). The Flatiron: The New York Landmark and the Incomparable City that Arose With It. New York: Thomas Dunne/St. Martin's. ISBN 978-0-312-38468-5.

- Berman, Mirian, Madison Square: The Park and Its Celebrated Landmarks. (2001) ISBN 1-58685-037-7

- Burrows, Edwin G. and Wallace, Mike (1999). Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-195-11634-8.

- Mendelsohn, Joyce. "Madison Square" in Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (1995). The Encyclopedia of New York City. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300055366., p. 711-712

- Mendelsohn, Joyce (1998), Touring the Flatiron: Walks in Four Historic Neighborhoods, New York: New York Landmarks Conservancy, ISBN 0-964-7061-2-1, OCLC 40227695

- Moscow, Henry (1978). The Street Book: An Encyclopedia of Manhattan's Street Names and Their Origins. New York: Hagstrom Company. ISBN 978-0-8232-1275-0.

- New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission; Dolkart, Andrew S.; Postal, Matthew A. (2009). Postal, Matthew A. (ed.). Guide to New York City Landmarks (4th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-28963-1.

- Patterson, Jerry E. Fifth Avenue: The Best Address (1998)

- White, Norval & Willensky, Elliot (2000). AIA Guide to New York City (4th ed.). New York: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0-8129-3107-5.

External links

[edit]- Madison Square Park Conservancy

- "Madison Square Park" on the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation website

- Madison Square Park News, online newspaper

![The fountain, a modern reproduction installed in 1990 based on the 1867 original, restored in 2015[27][28]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/59/Madison_Square_Park_fountain.jpg/120px-Madison_Square_Park_fountain.jpg)