Milk (2008 American film)

| Milk | |

|---|---|

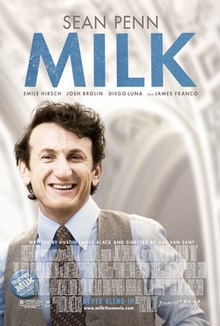

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Gus Van Sant |

| Written by | Dustin Lance Black |

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Harris Savides |

| Edited by | Elliot Graham |

| Music by | Danny Elfman |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Focus Features |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 128 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $20 million[2] |

| Box office | $54.6 million[2] |

Milk is a 2008 American biographical drama film based on the life of gay rights activist and politician Harvey Milk, who was the first openly gay man to be elected to public office in California, as a member of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors. Directed by Gus Van Sant and written by Dustin Lance Black, the film stars Sean Penn, Josh Brolin, and Victor Garber.

Attempts to put Milk's life to film followed a 1984 documentary of his life and the aftermath of his assassination, titled The Times of Harvey Milk, which was loosely based upon Randy Shilts's 1982 biography, The Mayor of Castro Street (the film won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature for 1984, and was awarded Special Jury Prize at the first Sundance Film Festival, among other awards). Various scripts were considered in the early 1990s, but projects fell through for different reasons, until 2007. Much of Milk was filmed on Castro Street and other locations in San Francisco, including Milk's former storefront, Castro Camera.

The film was released to critical acclaim and grossed $54 million worldwide. It earned numerous accolades from film critics and guilds for Penn's and Brolin's performances, Van Sant's directing, and Black's screenplay, it received eight Oscar nominations at the 81st Academy Awards, including Best Picture and went on to win two: Best Actor for Penn and Best Original Screenplay for Black.

Plot

[edit]The film opens with archival footage of police raiding gay bars and arresting patrons during the 1950s and 1960s, followed by Dianne Feinstein's November 27, 1978 announcement to the press that Harvey Milk and Mayor George Moscone had been assassinated. Milk is seen recording his will throughout the film, nine days (November 18, 1978) before the assassinations. The film then flashes back to New York City in 1970, the eve of Milk's 40th birthday and his first meeting with his much younger lover, Scott Smith.

Dissatisfied with his life and in need of a change, Milk and Smith decide to move to San Francisco in the hope of finding larger acceptance of their relationship. They open Castro Camera in the heart of Eureka Valley, a working-class neighborhood in the process of evolving into a predominantly gay neighborhood known as The Castro. Frustrated by the opposition they encounter in the once Irish-Catholic neighborhood, Milk utilizes his background as a businessman to become a gay activist, eventually becoming a mentor for Cleve Jones. Early on, Smith serves as Milk's campaign manager, but he grows frustrated with Milk's devotion to politics and leaves him. Milk later meets Jack Lira, a sweet-natured but unbalanced young man. As with Smith, Lira cannot tolerate Milk's devotion to political activism and eventually hangs himself. Milk clashes with the local gay "establishment", which he feels to be too cautious and risk-averse.

After two unsuccessful political campaigns in 1973 and 1975 to become a city supervisor and a third in 1976 for the California State Assembly, Milk finally wins a seat on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors in 1977 for District 5, after a change from at-large elections to district elections. His victory makes him the first openly gay man to be voted into major public office in California and the third openly homosexual politician in the entire US. Milk subsequently meets fellow Supervisor Dan White, a Vietnam veteran and former police officer and firefighter. White, who is politically and socially conservative, has a difficult relationship with Milk, and develops a growing resentment for Milk when he opposes projects that White proposes.

Milk and White forge a complex working relationship. Milk is invited to, and attends, the christening of White's first child, and White asks for Milk's assistance in preventing a psychiatric hospital from opening in White's district, possibly in exchange for White's support of Milk's citywide gay rights ordinance. When Milk fails to support White because of the negative effect it will have on troubled youth, White feels betrayed and ultimately becomes the sole vote against the gay rights ordinance. Milk also launches an effort to defeat Proposition 6, an initiative on the California state ballot in November 1978. Sponsored by John Briggs, a conservative state senator from Orange County, Proposition 6 seeks to ban gays and lesbians (in addition to anyone who supports them) from working in California's public schools. It is also part of a nationwide conservative movement that starts with the successful campaign headed by Anita Bryant and her organization Save Our Children in Dade County, Florida to repeal a local gay rights ordinance.

On November 7, 1978, after working tirelessly against Proposition 6, Milk and his supporters rejoice in the wake of its defeat. A desperate White favors a supervisor pay raise but does not get much support, and shortly after supporting the proposition resigns from the Board. He later changes his mind and asks to be reinstated. Mayor Moscone denies his request, after being lobbied by Milk.

On the morning of November 27, 1978, White enters City Hall through a basement window to conceal a gun from metal detectors. He requests another meeting with Moscone, who rebuffs his request for appointment to his former seat. Enraged, White shoots Moscone in his office and then goes to meet Milk, where he guns him down, with the fatal bullet delivered execution-style. The film suggests that Milk believed that White might be a closeted gay man.[3]

The last scene is a candlelight vigil held by thousands for Milk and Moscone throughout the streets of the city. Pictures of the actual people depicted in the film, and brief summaries of their lives follow.

Cast

[edit]

- Sean Penn as Harvey Milk

- Emile Hirsch as Cleve Jones

- Josh Brolin as Dan White

- Diego Luna as Jack Lira

- James Franco as Scott Smith

- Alison Pill as Anne Kronenberg

- Victor Garber as Mayor George Moscone

- Denis O'Hare as State Senator John Briggs

- Joseph Cross as Dick Pabich

- Stephen Spinella as Rick Stokes

- Lucas Grabeel as Danny Nicoletta

- Jeff Koons as Art Agnos

- Ashlee Temple as Dianne Feinstein

- Wendy Tremont King as Carol Ruth Silver

- Steven Wiig as McConnely

- Kelvin Han Yee as Gordon Lau

- Howard Rosenman as David Goodstein

- Ted Jan Roberts as Dennis Peron

- Robert Chimento as Phillip Burton

- Zachary Culbertson as Bill Kraus

- Mark Martinez as Sylvester

- Brent Corrigan as Telephone Tree #3

- Dave Franco as Telephone Tree #5

- Dustin Lance Black as Castro Clone

- Roman Alcides as City Hall Engineer

A number of Milk's associates, including speechwriter Frank M. Robinson, teamster Allan Baird and school teacher-turned-politician Tom Ammiano, portrayed themselves. Additionally, Carol Ruth Silver, who served with Milk on the Board of Supervisors and was allegedly also a target of the assassination, plays a small role as Thelma. Cleve Jones also has a small role as Don Amador. Anne Kronenberg makes an appearance as a stenographer, and Daniel Nicoletta appears as Carl Carlson.

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]In early 1991, Oliver Stone was planning to produce, but not direct, a film on Milk's life;[4] he wrote a script for the film, called The Mayor of Castro Street.[5] In July 1992, director Gus Van Sant was signed with Warner Bros. to direct the biopic with actor Robin Williams in the lead role.[6] By April 1993, Van Sant parted ways with the studio, citing creative differences.[7] Rob Cohen was signed to direct the film and wrote a script but Williams decided that the script was not right for him and dropped out. However, Warner Bros still planned to produce a film in 1994.[8][9] Other actors considered for Harvey Milk at the time included Richard Gere, Daniel Day-Lewis, Al Pacino, and James Woods.

In April 2007, the director sought to direct the biopic based on a script by Dustin Lance Black, while at the same time, director Bryan Singer was developing The Mayor of Castro Street, which had been in development hell.[10] By the following September, Sean Penn was attached to play Harvey Milk and Matt Damon was attached to play Milk's assassin, Dan White.[11] Damon pulled out later in September due to scheduling conflicts.[12] By November, Focus Features moved forward with Van Sant's production, Milk, while Singer's project ran into trouble with the writers' strike.[13] In December 2007, actors Josh Brolin, Emile Hirsch, Alison Pill, and James Franco joined Milk, with Brolin replacing Damon as Dan White.[14]

Filming

[edit]Milk began filming on location in San Francisco in January 2008.[15] The production design and costume design crew for the film researched the history of the city's gay community in the archives of the GLBT Historical Society in San Francisco, where they spent several weeks reviewing photographs, film and video, newspapers, historic textiles and ephemera, as well as the personal belongings of Harvey Milk, which were donated to the institution by the estate of Scott Smith.[16][17] The crew also talked to people who knew Milk to shape their approach to the era.

The filmmakers also revisited the location of Milk's camera shop on Castro Street and dressed the street to match the film's 1970s setting. The camera shop, which had become a gift shop, was bought out by the filmmakers for a couple of months to use in production. Production on Castro Street also revitalized the Castro Theatre, whose facade was repainted and whose neon marquee was redone. Filming also took place at the San Francisco City Hall, while White's office, where Milk was assassinated, was recreated elsewhere due to the city hall's offices having become more modern. Filmmakers also intended to show a view of the San Francisco Opera House from the redesign of White's office.[18] Filming finished March 2008.[19]

The film offers special thanks to The Times of Harvey Milk for "its enormous contribution to the making of this movie", and to its director and producer, Rob Epstein.[20]

Soundtrack

[edit]The music of the movie is composed by Danny Elfman under the label Decca Records.

Songs:

- "Queen Bitch" – David Bowie

- "Everyday People" – Sly & the Family Stone

- "Rock the Boat" – The Hues Corporation

- "You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real)" – Sylvester

- "Hello, Hello" – Sopwith Camel

- "Well Tempered Clavier (Bach)" – Swingle Singers

- "Till Victory" – Patti Smith Group

- "Over the Rainbow" – Judy Garland

Release

[edit]In the month leading up to Milk's release, Focus Features kept the film out of all film festivals and restricted media screenings, seeking to briefly avoid word-of-mouth and the partisanship it could generate. Milk premiered in San Francisco on October 28, 2008, initiating a marketing dilemma that Focus Features struggled to face due to the film's subject matter. The studio hoped to stay above the politics of the ongoing general elections, especially California's anti-gay-marriage Proposition 8, which parallels the anti-gay rights Proposition 6 that is explored in the film.[21]

Regardless, many reviewers and pundits have noted that the highly acclaimed film has taken on a new significance after the successful passage of Proposition 8 as a galvanizing point of honoring a major gay political and historical figure who would have strongly opposed the measure.[22][23] Gay activists called on Focus Features to pull the film from the Cinemark Theatres chain as part of a series of boycotts because Cinemark's chief executive, Alan Stock, donated $9,999 to the Yes on 8 campaign.[24][25]

The film was banned in Samoa for depicting homosexual themes.[26][27]

Box office

[edit]In the United States, Milk was given a limited release on November 26, 2008, and expanded to additional theaters each of the following weekends to a maximum of 882 screens. The film made the top 10 box office list on its opening weekend with earnings of $1.4 million in 36 theaters.[28] At the box office, the film more than doubled its production cost of $20 million.[29]

Home media

[edit]Milk was released on DVD and Blu-ray on March 10, 2009.[30] The DVD comes with deleted scenes and three featurettes: Remembering Harvey, Hollywood Comes to San Francisco, and Marching for Equality.

As of August 2009, the DVD release of the film has sold an estimated 600,413 units, resulting in $11.3 million in revenue.[31]

Reception

[edit]Critical response

[edit]As per the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 93% of critics have given the film a positive review based on 245 reviews, with an average rating of 8 out of 10. The site's critics consensus reads, "Anchored by Sean Penn's powerhouse performance, Milk is a triumphant account of America's first openly gay man elected to public office."[32] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 83 out of 100, with 95% positive reviews based on 39 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[33]

Todd McCarthy of Variety called the film "adroitly and tenderly observed", "smartly handled", and "most notable for the surprising and entirely winning performance by Sean Penn." He added, "while Milk is unquestionably marked by many mandatory scenes . . . the quality of the writing, acting and directing generally invests them with the feel of real life and credible personal interchange, rather than of scripted stops along the way from aspiration to triumph to tragedy. And on a project whose greatest danger lay in its potential to come across as agenda-driven agitprop, the filmmakers have crucially infused the story with qualities in very short supply today – gentleness and a humane embrace of all its characters."[34]

Kirk Honeycutt of The Hollywood Reporter said the film "transcends any single genre as a very human document that touches first and foremost on the need to give people hope" and added it "is superbly crafted, covering huge amounts of time, people and the zeitgeist without a moment of lapsed energy or inattention to detail . . . Black's screenplay is based solely on his own original research and interviews, and it shows: The film is richly flavored with anecdotal incidents and details. Milk surfaces in a season filled with movies based on real lives, but this is the first one that inspires a sense of intimacy with its subjects."[35]

A. O. Scott of The New York Times called Milk, "A Marvel", and wrote the film "is a fascinating, multi-layered history lesson. In its scale and visual variety it feels almost like a calmed-down Oliver Stone movie, stripped of hyperbole and Oedipal melodrama. But it is also a film that like Mr. Van Sant's other recent work – and also, curiously, like David Fincher's Zodiac, another San Francisco-based tale of the 1970s – respects the limits of psychological and sociological explanation."[36]

Christianity Today, a major Evangelical Christian periodical, gave the film a positive response.[22] It stated that "Milk achieves what it sets out to do, telling an inspiring tale of one man's quest to legitimize his identity, to give hope to his community. I'm not sure how well it'll play outside of big cities, or if it will sway any opinions on hot-button political issues, but it gives a valiant, empathetic go of it." It also stated that the portrayal of Dan White was very fair and humanized and portrayed as more of a tragically flawed character, rather than a "typical 'crazy Christian villain' stereotype".[22]

In contrast, John Podhoretz of the conservative magazine Weekly Standard blasted the portrayal of Harvey Milk, saying that it treated the "smart, aggressive, purposefully offensive, press-savvy" activist like a "teddy bear". Podhoretz also argued that the film glosses over Milk's polyamorous relationships; he opined that this contrasts Milk with present-day gay rights activists fighting over monogamous same-sex marriage. Podhoretz mentioned as well that the film concentrates on Milk's opposition to the Briggs Initiative while ignoring that both Governor Ronald Reagan and President Jimmy Carter had made more public statements against it.[37]

Screenwriter and journalist Richard David Boyle, who described himself as a former political ally of Milk's, stated that the film made a creditable effort at recreating the era. He also wrote that Penn captured Milk's "smile and humanity", and his sense of humor about his homosexuality. Boyle reserved criticism for what he felt was the film's inability to tell the whole story of Milk's election and demise.[38]

Luke Davies of The Monthly applauded the film for recreating "the atmosphere, the sense of hope and battle; even the sound design, bustling with street noise, adds much vibrancy to the tale", but voiced criticisms in regard to the message of the film, stating "while the film is a political narrative in a grand historical sense, the murder of Milk is neither a political assassination nor an act of homophobic rage. Rather, it is an act of revenge for perceived wrongs and public humiliation," Davies continues to postulate that "It seems as likely that Milk would have been murdered were he heterosexual. So the film can't be the heroic tale of a political martyr it needs to be in order to hold us and take our breath away. It's a simpler story, about a man who fought an extraordinary political fight and who was killed, arbitrarily and unnecessarily." Although Davies found Penn's portrayal of Milk moving, he adds that "on a minor but troubling note, there are times when Penn's version of 'gay' acting veers dangerously close to a twee version of his childlike (read: 'mentally retarded') acting in I Am Sam." All his criticisms aside, Davies concludes that "the heart of the film – and while it is not perfect, it is uplifting – lies in Penn's portrayal of Milk's generosity of spirit.[39]

The Advocate, while supporting the film in general, criticized the choice of Penn given the actor's support for the Cuban government despite the country's anti-gay rights record.[40] Human Rights Foundation president Thor Halvorssen said in the article "that Sean Penn would be honored by anyone, let alone the gay community, for having stood by a dictator that put gays into concentration camps is mind-boggling."[40] Los Angeles Times film critic Patrick Goldstein commented in response to the controversy, "I'm not holding my breath that anyone will be holding Penn's feet to the fire."[40]

Top ten lists

[edit]The film appeared on many critics' top ten lists of the best films of 2008.[41] Movie City News shows that the film appeared in 131 different top ten lists, out of 286 different critics lists surveyed, the 4th most mentions on a top ten list of the films released in 2008.[42]

Samoa ban

[edit]In late March 2009, Samoa's Censorship Board banned the film from distribution, without giving a reason.[43] Samoan human rights activist Ken Moala disputed the ban, commenting that "It's really harmless, I don't know how it would affect Samoan lifestyle. It is totally different and not applicable to here, it is pretty tame really."[43] The Pacific Freedom Forum issued a press release stating that "Samoa is the only nation worldwide where censors have specifically banned the multi-Academy Award winning film", limiting Samoans to smuggled or pirated versions.[44] American Samoan Monica Miller, the Forum's co-chair, stated, "Observers are left to wonder at the censorship standards being applied in a country where fa'afafine have a well established and respected role."[44] Fa'afafine are assigned male at birth but assume female gender roles, making them a third gender well accepted in Samoan society. The Fa'afafine Association also criticised the ban, describing it as a "reject[ion of] the idea of homosexuality".[45]

On April 30, Principal Censor Leiataua Niuapu released the reason for the ban, saying the film had been deemed "inappropriate and contradictory to Christian beliefs and Samoan culture": "In the movie itself it is trying to promote the human rights of gays. Some of the scenes are very inappropriate in regard to some of the sex in the film itself, it's very contrary to the way of life here in Samoa."[46] Samoan society is, in the words of the BBC, "deeply conservative and devoutly Christian".[47]

Accolades

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2012) |

Milk had received accolades from several film critics organizations.

- December 2, 2008,[48] the film received 4 nominations for the 24th Independent Spirit Awards and won 2, including Best Supporting Male (James Franco) and Best First Screenplay (Dustin Lance Black).[49]

- December 9, 2008, the film received eight Critic's Choice Award nominations, including Best Picture and Best Director.

- December 11, 2008, Sean Penn was nominated for a Golden Globe Award for Best Actor – Drama

- December 18, 2008, the Screen Actors Guild nominated Milk in three categories: Best Actor, Best Supporting Actor and Best Cast in a Motion Picture for the 15th Screen Actors Guild Awards; Sean Penn won Best Actor.

- January 5, 2009, the film's producers received a nomination for Producer of the Year for the 20th Producers Guild of America Awards.

- January 8, 2009, Gus Van Sant received a nomination for Outstanding Directing for the 61st Directors Guild of America Awards.

- The film won Best Original Screenplay at the 62nd Writers Guild of America Awards

- The film received 4 BAFTA nominations, including Best Film, for the 62nd British Academy Film Awards.

- January 22, 2009 the film received 8 Academy Award nominations, including Best Picture, and winning 2, Best Original Screenplay (Dustin Lance Black) and Best Actor (Sean Penn).

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "MILK (15)". Momentum Pictures. British Board of Film Classification. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ a b "Milk (2008)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ Edelstein D. "'Milk' Is Much More Than A Martyr Movie." NPR. November 26, 2008. Accessed on: January 3, 2009.

- ^ Stephen Talbot (1991). "Sixties something". Mother Jones. 16 (2): 47–9, 69–70.

- ^ Koltnow, Barry (December 4, 2008). "Orange County plays the villain in Harvey Milk movie". Orange County Register. Archived from the original on December 24, 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-27.

- ^ Toumarkine, Doris (July 15, 1992). "Van Sant set for Milk biopic". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Eller, Claudia (April 19, 1993). "Van Sant off of 'Castro St.'". Variety. Retrieved November 26, 2008.

- ^ Fleming, Michael (October 28, 1993). "Becker Storms Castle; Baldwin's at the gate". Daily Variety. p. 19.

- ^ "Clarification". Daily Variety. October 29, 1993. p. 4.

- ^ Fleming, Michael; McClintock, Pamela (April 12, 2007). "Dueling directors Milk a good story". Variety. Retrieved November 26, 2008.

- ^ Goldstein, Gregg (September 10, 2007). "Van Sant closes in on Milk tale". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Goldstein, Gregg (November 17, 2007). "Van Sant's 'Milk' a go for Jan". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Garrett, Diane (November 18, 2007). "Van Sant's 'Milk' pours first". Variety. Retrieved November 26, 2008.

- ^ Goldstein, Gregg; Borys Kit (December 5, 2007). "Hirsch, Franco, Brolin got 'Milk'". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Garrett, Diane (December 4, 2007). "Josh Brolin circles 'Milk' killer". Variety. Retrieved November 26, 2008.

- ^ Gordon, Larry (2008-11-20). "On film and in exhibits, a full picture of Milk". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- ^ Shapiro, Eddie (2008-12-01). "Remaking the Castro clone". OUT Magazine. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- ^ Kit, Borys (February 1, 2008). "'Milk' shoot does the Castro good". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Stein, Ruthe (March 18, 2008). "It's a wrap – 'Milk' filming ends in S.F." San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved November 26, 2008.

- ^ "Milk Production Notes" (PDF). Focus Features International. p. 49. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 18, 2016. Retrieved June 18, 2016.

- ^ Zeitchik, Steven (October 28, 2008). "Politics? Focus won't 'Milk' it". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ a b c "Milk". Christianity Today. Retrieved 2008-11-26.

- ^ Lim, Dennis (November 26, 2008). "Harvey Would Have Opened It in October". Slate.com.

- ^ Abramowitz, Rachel (November 25, 2008). "L.A. Film Festival director Richard Raddon resigns". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 3, 2008.

- ^ "No MILK for Cinemark!". nomilkforcinemark.com. Archived from the original on December 5, 2008. Retrieved December 4, 2008.

- ^ "Samoa bans gay rights movie 'Milk'". 13 June 2023.

- ^ "'Milk' banned in Samoa". Digital Spy. 14 April 2009.

- ^ http://www.boxofficeprophets.com/column/index.cfm?columnID=11142&cmin=10&columnpage=3%7CBox Office Prophets

- ^ "New Music Videos, Reality TV Shows, Celebrity News, Pop Culture | LOGOtv".

- ^ "Milk DVD Release". Archived from the original on 2011-09-21. Retrieved 2009-03-01.

- ^ "Milk (2008) – Financial Information".

- ^ "MILK". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- ^ "Milk". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved May 4, 2009.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (November 2, 2008). "Review of Milk". Variety. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved November 26, 2008.

- ^ Honeycutt, Kirk (November 2, 2008). "Film Review: Milk". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on February 9, 2015. Retrieved 2015-02-08.

- ^ A. O. Scott (2008-11-26). "Movie Review – Milk". The New York Times.

- ^ Rose-Colored Milk Archived 2011-06-04 at the Wayback Machine. By John Podhoretz. Weekly Standard. Published December 6, 2008. Accessed December 12, 2008.

- ^ Boyle, Richard David, "Local writer tells inside story of Milk". Archived from the original on December 21, 2008. Retrieved 2013-09-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link), Inland Valley Daily Bulletin, December 17, 2008 - ^ Davies, Luke, "Tales of the City: Gus Van Sant's Milk", The Monthly, March 2009, No.43

- ^ a b c Goldstein, Patrick (December 11, 2008). "'Milk' star Sean Penn: Pal of anti-gay dictators?". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 21, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae "Metacritic: 2008 Film Critic Top Ten Lists". Metacritic. Archived from the original on January 2, 2009. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ Poland, David (2008). "The 2008 Movie City News Top Ten Awards". Archived from the original on January 21, 2009. Retrieved 2009-01-25.

- ^ a b Jackson, Cherelle (April 9, 2009). "Samoa bans gay rights movie 'Milk'". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved October 25, 2011.

- ^ a b "MILK Ban Unhealthy For Samoa", Pacific Freedom Forum press release, April 19, 2009

- ^ "Film ban angers Samoan gay rights group" Archived 2011-07-17 at the Wayback Machine, ABC Radio Australia, May 1, 2009

- ^ "Samoa bans 'Milk' film" Archived 2012-02-19 at the Wayback Machine, ABC Radio Australia, April 30, 2009

- ^ "Country profile: Samoa", BBC, February 29, 2009

- ^ Saito, Stephen (December 2, 2008). "The 2009 Spirit Award Nominations". ifc.com. Retrieved April 28, 2012.

- ^ Independent Spirit Awards – Twenty-Six Years of Nominees & Winners Archived 2012-06-27 at the Wayback Machine

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Film's script

- "Van Sant Gives Castro a 'Milk' Bath"—CineSource article on film production in SF's Castro district

- Milk at IMDb

- Milk at Box Office Mojo

- Milk at Rotten Tomatoes

- Milk at Metacritic

- "The 34 best political movies ever made", Ann Hornaday, The Washington Post Jan. 23, 2020), ranked #30

- 2008 films

- 2008 biographical drama films

- 2000s historical drama films

- 2008 LGBTQ-related films

- 2000s political drama films

- American biographical drama films

- American historical drama films

- American LGBTQ-related films

- American political drama films

- Biographical films about activists

- Biographical films about LGBTQ people

- Biographical films about politicians

- 2000s English-language films

- Films about elections

- Films directed by Gus Van Sant

- Films featuring a Best Actor Academy Award–winning performance

- Films scored by Danny Elfman

- Films set in the 1970s

- Films set in 1978

- Films set in New York City

- Films set in San Francisco

- Films shot in San Francisco

- Films whose writer won the Best Original Screenplay Academy Award

- Films with screenplays by Dustin Lance Black

- Focus Features films

- Gay-related films

- Harvey Milk

- LGBTQ history in San Francisco

- 2000s LGBTQ-related drama films

- LGBTQ-related films based on actual events

- LGBTQ-related political films

- Political films based on actual events

- Drama films based on actual events

- Universal Pictures films

- 2008 drama films

- Films about anti-LGBTQ sentiment

- Censored films

- LGBTQ-related controversies in film

- Films produced by Bruce Cohen

- 2000s American films

- English-language historical drama films

- English-language biographical drama films