The Story of Temple Drake

| The Story of Temple Drake | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Stephen Roberts |

| Screenplay by | Oliver H.P. Garrett |

| Based on | Sanctuary by William Faulkner |

| Produced by | Benjamin Glazer |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Karl Struss |

| Music by | |

| Color process | Black and white |

Production company | Paramount Pictures |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 71 minutes[2][3] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

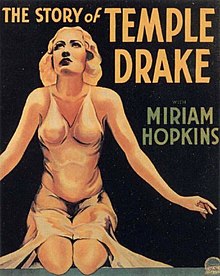

The Story of Temple Drake is a 1933 American pre-Code drama film directed by Stephen Roberts and starring Miriam Hopkins and Jack La Rue. It tells the story of Temple Drake, a reckless woman in the American South who falls into the hands of a brutal gangster and rapist. It was adapted from the highly controversial 1931 novel Sanctuary by William Faulkner. Though some of the more salacious elements of the source novel were not included, the film was still considered so indecent that it helped give rise to the strict enforcement of the Hays Code.

Long unseen except in bootleg 16mm prints, The Story of Temple Drake was restored by the Museum of Modern Art and re-premiered in 2011 at the TCM Classic Film Festival. The Criterion Collection released the film for the first time on DVD and Blu-ray in December 2019.

Plot

[edit]Temple Drake, the reckless granddaughter of a prominent judge in a small Mississippi town, refuses to marry her lawyer boyfriend, Stephen Benbow. This earns her a reputation in the town as a seductress. On the night of a town dance, Temple declines Stephen's proposal for a second time, and instead goes out with one of her suitors, Toddy Gowan. Toddy, who has been drinking, crashes their car near a dilapidated plantation home occupied by a speakeasy run by a man named Lee Goodwin. Trigger, a gangster and bootlegger at the speakeasy, forces Temple and Toddy into the house. Toddy, drunk and injured, attempts to fight off another drunk, who has grabbed at Temple, but the drunk knocks him unconscious. Temple tries to flee, but Trigger insists she spend the night. Lee's wife, Ruby, suggests that Temple sleep in the barn, and arranges for a young man named Tommy to stand watch.

At dawn, Trigger shoots Tommy to death before raping Temple in the barn. Trigger proceeds to kidnap Temple, making her his gun moll, and brings her to a brothel in the city run by a woman named Reba. Meanwhile, Toddy awakens in a warehouse and skips town. Newspapers erroneously report that the missing Temple has traveled to Pennsylvania to visit family. At the speakeasy, Lee is arrested for Tommy's murder, and Stephen is appointed as his lawyer. Fearing for his life, Lee refuses to implicate Trigger in Tommy's murder. Ruby, however, directs Stephen to search for Trigger at Reba's home.

Stephen tracks down Trigger to Reba's address, and finds Temple there, dressed in a negligee. Fearing that Trigger will kill Stephen, Temple falsely assures Stephen that she willingly went with him. Stephen believes her, and serves them summons for Tommy's murder trial. After Stephen leaves, Temple tries to escape, only to be attacked by Trigger. In the melee, Temple wrests his gun and shoots him to death.

Temple returns to her hometown, and near the conclusion of the trial, she begs Stephen to dismiss her from testifying. He denies her wish, and forces her to take the stand in court, but, out of his love for her, he is unable to question her about Trigger. Despite his lack of questioning, Temple openly confesses everything that happened, including her witnessing Tommy's murder, her rape, and her murder of Trigger. At the end of her confession, she loses consciousness, and Stephen carries her out of the courtroom.

Cast

[edit]- Miriam Hopkins as Temple Drake

- Jack La Rue as Trigger

- William Gargan as Stephen Benbow

- William Collier Jr. as Toddy Gowan

- Irving Pichel as Lee Goodwin

- Jobyna Howland as Miss Reba

- Guy Standing as Judge Drake, Temple's grandfather

- Elizabeth Patterson as Aunt Jennie

- Florence Eldridge as Ruby Lemarr

- James Eagles as Tommy

- Harlan Knight as Pap

- James Mason as Van

- Louise Beavers as Minnie

- Arthur Belasco as Wharton

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]

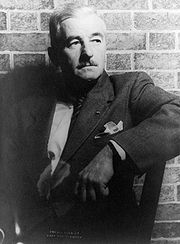

In 1932, Paramount Pictures acquired the rights to the film's basis, the controversial novel Sanctuary (1931) by William Faulkner, for $6,000.[4] Faulkner's novel dealt with a young Southern debutante held captive by a gang member and rapist.[2] As the public felt the novel had a racy reputation, the film received a new title as the plot had been made more mild and to avoid associating it with the source work.[1] Despite this, even before filming had begun, it was publicly condemned by U.S. women's leagues, an article in The New York Times, as well as the Roman Catholic Church.[5]

The credits only stated that Faulkner wrote the original novel. Robert Littell, who wrote a review of the film published in The New Republic on June 14, 1933, stated that the film producers also consulted Faulkner; statements about this are not present in the credits.[6]

Deviations from novel

[edit]Several alterations were made to the screenplay that deviated from the source material: For example, in the novel, the judge is Temple's father; Gene D. Phillips of Loyola University of Chicago stated that "presumably" to make it more believable that he is "ineffectual" with her, he was changed into being her grandfather.[7] For a short period before the film went into production, it was tentatively titled The Shame of Temple Drake.[1]

The relatively upbeat ending of the film is in marked contrast to the ending of Faulkner's novel Sanctuary, in which Temple perjures herself in court, resulting in the lynching of an innocent man. E. Pauline Degenfelder of Worcester Public Schools wrote that the characterization of Temple differs from that of the novel version,[8] and that the film gives her a "dual nature", dark and light.[9] Phillips wrote that she is "better" morally than the novel character.[10] According to Pre-Code scholar Thomas Doherty, the film implies that the deeds done to Temple are in recompense for her immorality in falling into a relationship with the gangster instead of fleeing him.[11]

Casting

[edit]

George Raft was initially cast as the male lead of Trigger,[12] but dropped out of the production, which resulted in his being temporarily suspended by Paramount.[1] Raft felt taking the role would be "screen suicide" as the character had no redeemable qualities,[13] and also demanded a salary of $2 million.[14] He was ultimately replaced by Jack La Rue, then a bit player for Paramount[13] who had garnered some notice for his performance in a Broadway production of Diamond Lil opposite Mae West.[14]

According to Filmink the fact the film ultimately "did little for La Rue’s career... served to give Raft a false idea of the quality of his instincts when it came to script selection. "[15]

Miriam Hopkins, who was cast in the titular role of Temple Drake, was a newcomer at the time of filming, and had only begun establishing herself in two Ernst Lubitsch films: The Smiling Lieutenant (1931) and Trouble in Paradise (1932).[13] Hopkins' mother was reportedly upset that her daughter was portraying a rape victim.[16] Hopkins herself would continually cite the role as one of her personal favorites due to its emotional complexity: "That Temple Drake, now, there was a thing. Just give me a nice un-standardized wretch like Temple three times a year! Give me the complex ladies, and I'll interpret the daylights out of them."[17]

Filming

[edit]Principal photography of The Story of Temple Drake began in mid-February 1933[14] on the Paramount Studio lot in Los Angeles, California.[18] According to biographer Allan Ellenberger, the mood on the set was "gloomy" due to the dark subject matter, and the cast members frequently played pranks on one another to lighten the mood.[19] Jean Negulesco, a sketch artist and technical advisor at Paramount, helped design and orchestrate the film's rape sequence.[16] Though the film only suggests the rape, as the scene concludes with Trigger approaching Temple, followed by her scream, Hopkins recalled that Negulesco had extensively "planned how it could be done... If you can call a rape artistically done, it was."[16]

Release

[edit]Censorship

[edit]Will H. Hays, who was in charge of the Motion Picture Production Code, had objected to any film adaptation of Sanctuary, and, after the film was made, forbade any reference to it in advertising materials.[1] However, Joseph I. Breen, who was in charge of public relations for the Hays Office, stated the finished film was so tame in comparison to Faulkner's novel that patrons who had read it and watched the film would "charge us with fraud."[1]

In March 1933, the Hays Office recommended several cuts be made before the film was released, with the central rape scene being of utmost concern.[1] In the original cut (and in Faulkner's novel), Temple's rape occurs in a corn crib, and she is at one point penetrated with a corn cob during the assault; the sequence also featured shots in which the corncob is picked up by Trigger and examined after the rape.[1][19] These shots were allegedly only supposed to be included in rushes and not in the final cut, but were considered obscene enough that the Hays Office ordered Paramount to reshoot the rape sequence in a barn, and mandated that no footage of a corncob could be shown.[1] The scenes at Reba's home were also "portrayed too graphically," according to the Hays Office, and they ordered Paramount to excise footage and dialogue that indicated that the home was a brothel.[1] It was now portrayed, despite nude statuary, as a boarding house.[20] Some lines were cut, while Ruby's use of the word "chippie" (a slang term for a woman of low morals) was occluded by a clap of thunder.[1]

Because the film was considered so scandalous, it has been credited with spurring the strict enforcement of the Hays Code.[21][22]

Box office

[edit]The Story of Temple Drake premiered theatrically in the United States on May 12, 1933.[1] According to film historian Lou Sabini, it was one of the highest-earning films of the year.[23]

Critical response

[edit]Several protests and critical articles in newspapers appeared after the production company had purchased the rights before the release of the film.[7] Phillips wrote that some critics, while acknowledging the murder of Trigger would be justifiable, believed that it was wrong for the film to justify it.[24] A review published in The Washington Times lambasted the film, describing it as "trash," while the New York American deemed it "shoddy, obnoxiously disagreeable... trashy, sex-plugged piece."[25] Edwin Schallert of the Los Angeles Times was similarly unimpressed, describing the film as "deliberately sordid, unsympathetic, and nearly offensive," as well as "crudely realistic."[26]

Some critics were more favorable in their responses, such as Martin Dickson of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, who deemed the film a "compelling, if not always pleasant, photodrama," adding that Hopkins brings "a vital and credible characterization to the part."[27] The Atlanta Constitution also praised Hopkins' performance as "outstanding," and also praised La Rue as "excellent."[28] Mordaunt Hall of The New York Times heralded the cast as "well chosen," also adding that "Miss Hopkins delivers a capital portrayal."[29]

Home media

[edit]The Story of Temple Drake largely remained unavailable to the public after its initial theatrical release,[30] never even receiving television airings in the United States.[23] The Museum of Modern Art restored the film in 2011 and subsequently screened it to the public.[30] The Criterion Collection released the film on Blu-ray and DVD for the first time on December 3, 2019.[31]

Legacy

[edit]Faulkner stated that initially he wished to end the plot at the end of Sanctuary but he decided that, in Degenfelder's words, "Temple's reinterpretation would be dramatic and worthwhile."[6] Degenfelder believes that he may have gotten inspiration for the sequel, Requiem for a Nun, from The Story of Temple Drake due to common elements between the two.[6]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "The Story of Temple Drake". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Los Angeles, California: American Film Institute. Archived from the original on November 20, 2019.

- ^ a b Sabini 2017, p. 219.

- ^ Vermilye 1985, p. 104.

- ^ Ellenberger 2017, p. 79.

- ^ Sabini 2017, p. 220.

- ^ a b c Degenfelder 1976, p. 552.

- ^ a b Phillips 1973, p. 265.

- ^ Degenfelder 1976, p. 548.

- ^ Degenfelder 1976, p. 549.

- ^ Phillips 1973, p. 267.

- ^ Doherty 1999, pp. 117–118.

- ^ "Projection jottings". The New York Times. New York City, New York. February 19, 1933. p. X5.

- ^ a b c Sabini 2017, p. 221.

- ^ a b c Ellenberger 2017, p. 81.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (February 9, 2020). "Why Stars Stop Being Stars: George Raft". Filmink.

- ^ a b c Ellenberger 2017, p. 82.

- ^ Ellenberger 2017, p. 85.

- ^ Ellenberger 2017, pp. 80–84.

- ^ a b Ellenberger 2017, p. 83.

- ^ Campbell, Russell (1997). "Prostitution and Film Censorship in the USA". Screening the Past (2): C/7. Retrieved 2020-07-05.

- ^ "The Story of Temple Drake". AllMovie. Retrieved November 20, 2019.

- ^ Sabini 2017, p. 122.

- ^ a b Sabini 2017, p. 222.

- ^ Phillips 1973, p. 268.

- ^ Ellenberger 2017, p. 84.

- ^ Schallert, Edwin (June 3, 1933). "Temple Drake's Story Relate". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California. p. 21 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Dickson, Martin (May 22, 1933). "The Screen". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, New York. p. 9 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Miriam Hopkins at Paramount in 'Story of Temple Drake'". The Atlanta Constitution. Atlanta, Georgia. May 14, 1933. p. 18 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hall, Mordaunt (May 6, 1933). "Miriam Hopkins and Jack LaRue in a Pictorial Conception of a Novel by William Faulkner". The New York Times. New York City, New York. Archived from the original on November 20, 2019.

- ^ a b Morra, Anne (December 8, 2011). "Temple Drake: Was She Ever Lost?". Museum of Modern Art. Archived from the original on February 7, 2017.

- ^ "The Story of Temple Drake". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved November 20, 2019.

Sources

[edit]- Degenfelder, E. Pauline (Winter 1976). "The Four Faces of Temple Drake: Faulkner's Sanctuary, Requiem for a Nun, and the Two Film Adaptations". American Quarterly. 28 (5): 544–560. doi:10.2307/2712288. JSTOR 2712288.

- Doherty, Thomas Patrick (1999). Pre-Code Hollywood: Sex, Immorality, and Insurrection in American Cinema 1930-1934. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 117–8. ISBN 0-231-11094-4.

- Ellenberger, Allan R. (2017). Miriam Hopkins: Life and Films of a Hollywood Rebel. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-813-17433-4.

- Phillips, Gene D. (Summer 1973). "Faulkner And The Film: The Two Versions Of "Sanctuary"". Literature/Film Quarterly. 1 (2). Salisbury University: 263–273. JSTOR 43795435.

- Sabini, Lou (2017). Sex In the Cinema: The Pre-Code Years (1929-1934). Albany, Georgia: BearManor Media. ISBN 978-1-629-33107-2.

- Vermilye, Jerry (1985). The Films of the Thirties. New York: Citadel Press. ISBN 978-0-806-50971-6.

External links

[edit]- 1933 films

- 1933 crime drama films

- American black-and-white films

- American crime drama films

- Films about rape in the United States

- Films about prostitution in the United States

- Films based on American novels

- Films based on works by William Faulkner

- Films directed by Stephen Roberts

- American feminist films

- Films set in Mississippi

- Films shot in Los Angeles

- Paramount Pictures films

- American rape and revenge films

- Southern Gothic films

- Films scored by Karl Hajos

- 1930s English-language films

- 1930s American films

- Films scored by Bernhard Kaun

- Films scored by John Leipold

- English-language crime drama films