Venezuelan presidential crisis

| Venezuelan presidential crisis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the crisis in Venezuela | |||

Juan Guaidó (left) and Nicolás Maduro (right) | |||

| Date | 10 January 2019 – 5 January 2023 (3 years, 11 months and 26 days) | ||

| Location | |||

| Caused by |

| ||

| Goals |

| ||

| Methods | Protests, support campaigns, foreign diplomatic pressure and international sanctions | ||

| Resulted in | Status quo

| ||

| Parties | |||

| Lead figures | |||

| Crisis in Venezuela |

|---|

|

|

|

The Venezuelan presidential crisis was a political crisis concerning the leadership and the legitimate president of Venezuela between 2019 and 2023, with the nation and the world divided in support for Nicolás Maduro or Juan Guaidó.

Venezuela is engulfed in a political and economic crisis which has led to more than seven million people leaving the country since 2015. The process and results of the 2018 presidential elections were widely disputed.[1][2] The opposition-majority National Assembly declared Maduro a usurper of the presidency on the day of his second inauguration and disclosed a plan to set forth its president Guaidó as the succeeding acting president of the country under article 233 of the Venezuelan Constitution.[2][5] A week later, the Supreme Tribunal of Justice declared that the presidency of the National Assembly was the "usurper" of authority and declared the body to be unconstitutional.[2] Minutes after Maduro took the oath as president, the Organization of American States (OAS) approved a resolution in a special session of its Permanent Council declaring Maduro's presidency illegitimate and urging new elections.[6] Special meetings of the OAS on 24 January and in the United Nations Security Council on 26 January were held but no consensus was reached. Secretary-General of the United Nations António Guterres called for dialogue.[7] During the 49th General Assembly of the Organization of American States on 27 June, Guaidó's presidency was recognized by the organization.[8] Guaidó and the National Assembly declared he was acting president and swore himself in on 23 January.[4]

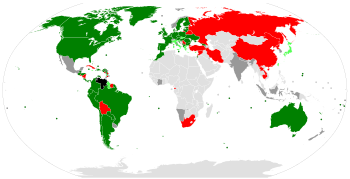

At his peak, Guaidó was recognized as legitimate by about 60 countries, despite never running as president; Maduro by about 20 countries.[9][10][11] However, Guaidó's international support waned over time.[12] Internationally, support followed geopolitical lines, with Russia, China, Cuba, Iran, Syria, and Turkey supporting Maduro, while the majority of Western and Latin American countries supported Guaidó as acting president.[9][13][14] Support for Guaidó began to decline when a military uprising attempt in April 2019 failed to materialize.[15][16] Following the failed uprising, representatives of Guaidó and Maduro began mediation, with the assistance of the Norwegian Centre for Conflict Resolution.[17] After the second meeting in Norway, no deal was reached.[18] In July 2019 negotiations started again in Barbados with representatives from both sides.[19][20][21] In September, Guaidó announced the end of dialogue following a forty-day absence by the Maduro government as a protest against the recent sanctions by the United States. In March 2020, the United States proposed a transitional government that would exclude both Maduro and Guaidó from the presidency.[22] U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said that sanctions did not apply to humanitarian aid during the coronavirus pandemic health emergency and that the United States would lift all sanctions if Maduro agreed to organize elections that did not include himself.[23] Guaidó accepted the proposal,[24] while Venezuela's foreign minister, Jorge Arreaza, rejected it.[25]

By January 2020, efforts led by Guaidó to create a transitional government had been unsuccessful and Maduro continued to control Venezuela's state institutions.[26][27][28] In January 2021, the European Union stopped recognizing Guaidó as president, but still did not recognize Maduro as the legitimate president;[29] the European Parliament reaffirmed its recognition of Guaidó as president,[30][31] and the EU threatened with further sanctions.[29] After the announcement of regional elections in 2021, Guaidó announced a "national salvation agreement" and proposed the negotiation with Maduro with a schedule for free and fair elections, with international support and observers, in exchange for lifting international sanctions.[32]

In December 2022, three of the four main opposition political parties (Justice First, Democratic Action and A New Era) backed and approved a reform to dissolve the interim government and create a commission of five members to manage foreign assets, as deputies sought a united strategy ahead of the 2024 Venezuelan presidential election,[33][34] stating that the interim government had failed to achieve the goals it had set.[35]

Background

[edit]Since 2010, Venezuela has been suffering a socioeconomic crisis under Nicolás Maduro and briefly under his predecessor Hugo Chávez, as rampant crime, hyperinflation and shortages as a result of sanctions, diminish the quality of life.[36][37] Javier Corrales stated in a 2020 Journal of Democracy that Maduro "presided over one of the most devastating national economic crises seen anywhere in modern times."[38] As a result of discontent with the government, the opposition was elected to hold the majority in the National Assembly for the first time since 1999 following the 2015 parliamentary election.[39] After the election, the lame duck National Assembly consisting of Bolivarian officials filled the Supreme Tribunal of Justice, the highest court in Venezuela, with Maduro allies.[39][40] The tribunal stripped three opposition lawmakers of their National Assembly seats in early 2016, citing alleged "irregularities" in their elections, thereby preventing an opposition supermajority which would have been able to challenge President Maduro.[39]

In January 2016, the National Assembly declared a "health humanitarian crisis" given the "serious shortage of medicines, medical supplies and deterioration of humanitarian infrastructure", asking Maduro's government to "guarantee immediate access to the list of essential medicines that are basic and indispensable and that must be accessible at all times."[41]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

The tribunal approved several actions by Maduro and granted him more powers in 2017.[39] As protests mounted against Maduro, he called for a constituent assembly that would draft a new constitution to replace the 1999 Venezuela Constitution created under Chávez.[42] According to Rafael Villa – writing in Defence Studies in 2022 – "Maduro's leadership [was] not consensual" and among the changes he had made to overcome his "political fragility" was promoting an excessive number of officers within the military, and the election of a 2017 Constituent National Assembly to replace the opposition-led National Assembly, which was elected in 2015.[43][44] Many countries considered these actions a bid by Maduro to stay in power indefinitely,[45] and over 40 countries stated that they would not recognize the 2017 Constituent National Assembly (ANC).[46][47] The Democratic Unity Roundtable, the main opposition to the incumbent ruling party, boycotted the election, saying that the ANC was "a trick to keep [the incumbent ruling party] in power."[48] Since the opposition did not participate in the election, the Great Patriotic Pole coalition and its supporters, including the incumbent United Socialist Party of Venezuela, won all seats in the assembly by default.[49] On 8 August 2017, the ANC declared itself to be the government branch with supreme power in Venezuela, banning the opposition-led National Assembly from performing actions that would interfere with the assembly while continuing to pass measures in "support and solidarity" with President Maduro, effectively stripping the National Assembly of all its powers.[50]

Maduro disavowed the National Assembly in 2017.[51][52] As of 2018, some considered the National Assembly the only "legitimate" institution left in the country[a] and human rights organizations said there were no independent institutional checks on presidential power.[b]

2018 election and calls for transitional government

[edit]

In February 2018, Maduro called for presidential elections four months before the prescribed date.[66] He was declared the winner in May 2018 after multiple major opposition parties were banned from participating, among other irregularities; many said the elections were invalid.[67] Some politicians both internally and internationally said Maduro was not legitimately elected[68] and considered him an ineffective dictator.[69] In the months leading up to his 10 January 2019 inauguration, Maduro was pressured to step down by nations and bodies including the Lima Group (excluding Mexico), the United States and the OAS; this pressure was increased after the new National Assembly of Venezuela was sworn in on 5 January 2019.[70][71] Between the May 2018 presidential election and Maduro's inauguration, there were calls to establish a transitional government.[72][73]

Signs of impending crisis showed when a Supreme Tribunal Justice and Electoral Justice seen as close to Maduro defected to the United States just a few days before the 10 January 2019 second inauguration of Nicolás Maduro. The justice, Christian Zerpa, said that Maduro was "incompetent" and "illegitimate".[70][71][74] Minutes after Maduro took the oath as president of Venezuela, the OAS approved a resolution in a special session of its Permanent Council declaring Maduro's presidency illegitimate and urging new elections.[6] Maduro's election was supported by Turkey, Russia, China, and the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America (ALBA).[75][76][77]

In December 2018, Guaidó had traveled to Washington, D.C., met with OAS Secretary General Luis Almagro. On 14 January 2019, he traveled to Colombia for a Lima Group meeting, in which Maduro's mandate was rejected. According to an article in El País, the January Lima Group meeting and the stance taken by Canadian Minister of Foreign Affairs Chrystia Freeland were key. El País describes Donald Trump's election—coinciding with the election of conservative presidents in Colombia and Brazil, along with deteriorating conditions in Venezuela—as "a perfect storm", with decisions influenced by U.S. officials including Vice President Mike Pence, Secretary of State Pompeo, National Security Advisor John Bolton and legislators Mario Díaz-Balart and Marco Rubio. Venezuelans Carlos Vecchio, Julio Borges and Gustavo Tarre were consulted and the Trump administration decision to back Guaidó formed on 22 January, according to El País. Díaz-Balart said that the decision was the result of two years of planning.[78]

Justification for the challenge

[edit]The Venezuelan opposition says its actions are based on the 1999 Constitution of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, specifically Articles 233, 333 and 350.[79]

The first paragraph of Article 233 states that "when the president-elect is absolutely absent before taking office, a new election shall take place [...] And while the president is elected and takes office, the interim president shall be the president of the National Assembly."[80][c][d]

Article 333 calls for citizens to restore and enforce the Constitution if it is not followed.[80][c] Article 350 calls for citizens to "disown any regime, legislation or authority that violates democratic values, principles and guarantees or encroaches upon human rights."[82][83][c]

Article 233 was invoked after the death of Hugo Chávez in 2013, which took place soon after his inauguration, and extraordinary elections were called within thirty days.[84][85] Invoked by the National Assembly, Guaidó was declared acting president until elections could be held; Diego A. Zambrano, an assistant professor of law at Stanford Law School, says that "Venezuelan lawyers disagree on the best reading of this provision. Some argue Guaidó can serve longer if the electoral process is scheduled within a reasonable time."[86] The National Assembly announced that it will designate a committee to appoint a new National Electoral Council, in anticipation of free elections.[87]

2019 events

[edit]Inauguration of Maduro

[edit]In January 2019, Leopoldo López's Popular Will party attained the leadership of the National Assembly of Venezuela according to a rotation agreement made by opposition parties, naming Juan Guaidó as president of the legislative body.[88]

Guaidó began motions to form a provisional government shortly after assuming his new role on 5 January 2019, stating that whether or not Maduro began his new term on the 10th, the country would not have a legitimately elected president in either case,[89][non-primary source needed] calling for soldiers to "enforce the Constitution"[90][non-primary source needed] Signs of impending crisis showed when a Supreme Court Justice and Electoral Justice seen as close to Maduro defected to the United States just a few days before the 10 January 2019 second inauguration of Nicolás Maduro. The justice, Christian Zerpa, said that Maduro was "incompetent" and "illegitimate".[91][92][74] Minutes after Maduro took the oath as president of Venezuela, the OAS approved a resolution in a special session of its Permanent Council declaring Maduro's presidency illegitimate and urging new elections.[93] Maduro's election was supported by Turkey, Russia, China, and the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America (ALBA).[76][77]

Guaidó announced a public assembly, referred to as an open cabildo, on 11 January, a rally in the streets of Caracas, where Guaidó spoke on behalf of the National Assembly saying that the country had fallen into a de facto dictatorship and had no leader.[94][95] Guaidó said that the National Assembly would "take the responsibility that touches us".[95] Leaders of other political parties, trade unions, women, and students also spoke at the rally.[96][non-primary source needed] The opposition considered assuming the powers of the executive branch legitimate based on constitutional processes; The National Assembly specifically invoked Articles 233, 333, and 350 of the Constitution.[97][96] Guaidó announced nationwide protests to be held on 23 January—the same day as the removal of Marcos Pérez Jiménez in 1958—using a slogan chant of ¡Sí se puede!.[97][98] The National Assembly worked with the coalition Frente Amplio Venezuela Libre to create a plan for the demonstrations, organizing a unified national force.[99] On 11 January, plans to offer incentives for the armed forces to disavow Maduro were announced.[100]

Guaidó declared acting president

[edit]

During Guaidó's speech, he said he was "willing to assume command ... only possible with the help of Venezuelans".[5] Following Guaidó's speech, the National Assembly released a press statement saying that Guaidó had assumed the role of acting president. The Assembly retracted the statement later published another clarifying Guaidó's position as "willing to assume command ... only possible with the help of Venezuelans".[5]

Maduro's response was to call the opposition a group of "little boys", describing Guaidó as "immature". The Minister for Prison Services, Iris Varela, threatened that she had picked out a prison cell for Guaidó and asked him to be quick in naming his cabinet so she could prepare prison cells for them as well.[101]

The president of the Supreme Tribunal of Justice of Venezuela in exile, based in Panama, wrote to Guaidó, requesting him to become acting president of Venezuela.[102] OAS Secretary-General Luis Almagro was the first to give international official support to Guaidó's claim, tweeting "We welcome the assumption of Juan Guaidó as interim president of Venezuela in accordance with Article 233 of the Political Constitution. You have our support, that of the international community and of the people of Venezuela."[97] Later that day, Brazil and Colombia gave their support to Guaidó as acting president of Venezuela.[103]

Guaidó briefly detained, plans continue

[edit]Guaidó was detained on 13 January by the Bolivarian Intelligence Service (SEBIN)[104] and released 45 minutes later.[105] The SEBIN agents who intercepted his car and took him into custody were fired.[106][107] The Information Minister, Jorge Rodríguez, said the agents did not have instructions and the arrest was orchestrated by Guaidó as a "media stunt" to gain popularity; BBC News correspondents said that it appeared to be a genuine ambush to send a message to the opposition.[106] Almagro condemned the arrest, which he called a "kidnapping", while Pompeo referred to it as an "arbitrary detention".[108] After his detention, Guaidó said that Rodríguez's admission that the SEBIN agents acted independently showed that the government had lost control of its security forces; he called Miraflores (the presidential palace) "desperate",[106][108] and stated: "There is one legitimate president of the National Assembly and of all Venezuela."[109]

On 15 January 2019, the National Assembly approved legislation to work with dozens of foreign countries to request that these nations freeze Maduro administration bank accounts.[110] Guaidó wrote a 15 January 2019 opinion piece in The Washington Post entitled "Maduro is a usurper. It's time to restore democracy in Venezuela"; he outlined Venezuela's erosion of democracy and his reasoning for the need to replace Maduro on an interim basis according to Venezuela's constitution.[111]

On 21 January, over two dozen National Guardsmen participated in a mutiny against Maduro with the assistance of residents in the area during the early morning hours. Government forces repressed the protestors tear gas and the officers were later captured.[112][113] During the night, over thirty communities in Caracas and surrounding areas participated in strong protests against the Maduro government.[114] The strongest protests occurred in San José de Cotiza, where the rebel National Guardsmen were arrested, with demonstrations spreading throughout nearby communities, with cacerolazos heard throughout Caracas.[114] One woman who was confused for a protester was killed in San José de Cotiza by members of a colectivo, who stole her phone.[115] On 22 January, Vice President Mike Pence called Guaidó personally and assured him that the United States would support his declaration.[116]

Guaidó declares himself acting president

[edit]On 23 January, Guaidó swore to serve as acting president.[4] On that morning, Guaidó tweeted, "The world's eyes are on our homeland today."[117][118] On that day, millions of Venezuelans[119] demonstrated across the country and world in support of Guaidó,[120][121] with a few hundred supporting Maduro outside Miraflores.[122][123] At one end of the blocked street was a stage where Guaidó spoke and took an oath to serve as interim president.[124][125][126] Minutes after his speech, the United States announced that it recognized Guaidó as interim president while presidents Iván Duque of Colombia and Jair Bolsonaro of Brazil, beside deputy Canadian prime minister Chrystia Freeland, announced at the World Economic Forum that they too recognized him.[116]

The Venezuelan National Guard used tear gas on gathering crowds at other locations,[124] and blocked protesters from arriving.[117] Some protests grew violent,[127] and at least 13 people were killed.[128] Michelle Bachelet of the United Nations requested a UN investigation into the security forces' use of violence.[129]

Guaidó began to appoint individuals in late January to serve as aides or diplomats, including Carlos Vecchio as the Guaidó administration's diplomatic envoy to the US,[130] Gustavo Tarre to the OAS,[131] and Julio Borges to represent Venezuela in the Lima Group.[132] He announced that the National Assembly had approved a commission to implement a plan for the reconstruction of Venezuela,[133][134] called Plan País (Plan for the Country),[135] and he offered an Amnesty law, approved by the National Assembly, for military personnel and authorities who help to "restore constitutional order".[136][137] The Statute Governing the Transition to Democracy was approved by the National Assembly on 5 February.[138]

As of July 2019, the National Assembly had approved Juan Guaidó's appointment has named 37 ambassadors and foreign representatives to international organizations and nations abroad.[139][140][141][142]

Maduro response

[edit]Maduro accused the United States of backing a coup and said he would cut ties with them.[148] He said Guaidó's actions were part of a "well-written script from Washington" to create a puppet state of the United States,[149] and appealed to the American people in a 31 January video, asking them not to "convert Venezuela into another Vietnam".[150]

Maduro asked for dialogue with Guaidó, saying "if I have to go meet this boy in the Pico Humboldt at three in the morning I am going, [...] if I have to go naked, I am going, [I believe] that today, sooner rather than later, the way is open for a reasonable, sincere dialogue".[151] He stated he would not leave the presidential office, saying that he was elected in compliance with the Venezuelan constitution.[152] With the two giving speeches to supporters at the same time, Guaidó replied to Maduro's call for dialogue, saying he would not initiate diplomatic talks with Maduro because he believed it would be a farce and fake diplomacy that could not achieve anything.[153]

On 18 February, Maduro's government expelled a group of Members of the European Parliament that planned to meet Guaidó.[154] The expulsion was condemned by Guaidó as well as Pablo Casado, president of the Spanish People's Party, and the Colombian government.[155] Maduro's Foreign Minister Jorge Arreaza defended the expulsions,[156] saying that the constitutional government of Venezuela "will not allow the European extreme right to disturb the peace and stability of the country with another of its gross interventionist actions."[157]

Humanitarian aid crisis

[edit]Shortages in Venezuela have been present since 2007 during the presidency of Hugo Chávez.[158] In 2016, the National Assembly of Venezuela declared a humanitarian crisis, asking Maduro's government to provide access to essential medicines and medical supplies.[41] Before the presidential crisis, the Maduro government denied several offers of aid, stating that there was not a humanitarian crisis and that such claims were used to justify foreign intervention.[159] Maduro's refusal of aid worsened the effects of Venezuela's crisis.[159] During the presidential crisis, Maduro initially refused aid, stating that Venezuela is not a country of "beggars".[160]

Guaidó made bringing humanitarian aid to the country a priority.[161] In early February, Maduro prevented the American-sponsored aid from entering Venezuela via Colombia,[161][162] and Venezuela's communications minister, Jorge Rodriguez, said there was a plot between Colombia, the CIA and exiled Venezuelan politician Julio Borges to oust Maduro.[163] Humanitarian aid intended for Venezuela was also stockpiled on the Brazilian border,[164] and two indigenous Pemon people were killed as they attempted to block military vehicles from entering the area, when members of armed forces loyal to Maduro fired upon them with live ammunition.[165][166][167]

Guaidó issued an ultimatum to the Venezuelan Armed Forces, stating that humanitarian aid would enter Venezuela on 23 February and that the armed forces "will have to decide if it will be on the side of the Venezuelans and the Constitution or the usurper".[168] Guaidó defied the restriction imposed by the Maduro administration on him leaving Venezuela, secretly crossed the border,[169] saying that with the help of the Venezuelan military,[170] and appeared at the Venezuela Aid Live concert in Cúcuta, Colombia on 22 February,[171] also to be present for the planned delivery of humanitarian aid.[170][172] Testing Maduro's authority, he was met by presidents Iván Duque of Colombia,[171][173] Sebastián Piñera from Chile,[174] and Mario Abdo Benítez from Paraguay,[175] as well as the OAS Secretary-General Luis Almagro.[173]

On 23 February, trucks with humanitarian aid attempted to enter Venezuela from Brazil and Colombia;[176][177] the attempts failed, with only one truck able to deliver aid.[178] At the Colombia–Venezuela border, the caravans were tear-gassed or shot at with rubber bullets by Venezuelan personnel.[179][180] The National Guard repressed demonstrations on the Brazilian border and colectivos attacked protesters near the Colombian border,[181][182] leaving at least four dead,[183][184] and more than 285 injured.[185]

Lima Group meeting and Latin American tour

[edit]

Guaidó traveled from Cúcuta to Bogotá for a 24 February meeting with US Vice President Mike Pence,[186][187] and a 25 February meeting of the Lima Group.[188][189] The group urged the International Criminal Court to pursue charges of crimes against humanity for the Maduro administration's use of violence against civilians and blockade of humanitarian aid.[190][191]

Pence did not rule out the use of US military force.[188] The Venezuelan government responded saying that Pence was trying to order others to take the country's assets, and saying that its basic rights were being disregarded in a campaign to unseat Maduro.[189] Brazil's vice president said it would not permit its territory to be used to invade Venezuela,[192] and the European Union cautioned against the use of military force.[189][193] The Lima Group rejected the use of force as well.[190] The US FAA warned pilots not to fly below 26,000 feet over Venezuela,[194] and US military officials said they had flown reconnaissance flights off the coast of Venezuela to gather classified intelligence about Maduro.[195]

From Bogotá, Guaidó embarked on a regional tour to meet with the presidents of Brazil, Paraguay, Argentina, and Ecuador,[196] to discuss ways to rebuild Venezuela and defeat Maduro.[197] Guaidó's trip was approved by Venezuela's National Assembly, as required by the Constitution of Venezuela,[198] but he faced the possibility of being imprisoned when returning to Venezuela because of the travel restriction placed upon him by the Maduro administration.[196][199] He re-entered Venezuela on 4 March, via Simón Bolívar International Airport in Maiquetía, and was received at the airport by diplomats[g] and in Caracas by a crowd of supporters.[200][201] German ambassador Daniel Kriener was accused of interference in internal affairs and expelled from Venezuela because of his role in helping Guaidó re-enter.[200][202]

Blackouts

[edit]

In March 2019, Venezuela experienced a near total electrical blackout, and lost 150,000 barrels per day in crude oil production during the blackout.[204][205] Full recovery of oil production was expected to take months,[206] but by April, Venezuela's exports were steady at a million barrels daily, "partially due to inventory drains".[207]

Experts and state-run Corpoelec (Corporación Eléctrica Nacional) sources attributed the electricity shortages to lack of maintenance, underinvestment, corruption and to a lack of technical expertise in the country resulting from a brain drain;[208][209][210] Nicolás Maduro's administration attributes them to sabotage.[211][212][213] Guaidó said that Venezuela's largest-ever power outage was "the product of the inefficiency, the incapability, the corruption of a regime that doesn't care about the lives of Venezuelans",[214] Maduro's Attorney General, Tarek William Saab, called for an investigation of Guaidó, alleging that he had "sabotaged" the electric sector.[214]

While Maduro visited hydroelectric facilities in Ciudad Guayana on 16 March, promising to restructure the state-run power company Corpoelec, his Vice President Delcy Rodríguez announced that Maduro would restructure his administration, asking the "entire executive Cabinet to put their roles up for review".[215] Guaidó announced he would embark on a tour of the country beginning 16 March, to organize committees for Operation Freedom with the goal to claim the presidential residence, Miraflores Palace.[216] From the first rally in Carabobo state, he said, "We will be in each state of Venezuela and for each state we have visited the responsibility will be yours, the leaders, the united, [to] organize ourselves in freedom commands."[216]

United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) commissioner Michelle Bachelet's office sent a five-person delegation to Venezuela in March.[217][218] On 20 March, Bachelet delivered a preliminary oral report before the UN Human Rights Council,[219][220] in which she outlined a "devastating and deteriorating" human rights situation in Venezuela, expressed concern that sanctions would worsen the situation, and called on authorities to show a true commitment to recognizing and resolving the situation.[221]

Elvis Amoroso, Maduro's comptroller, alleged in March that Guaidó had not explained how he paid for his February 2019 Latin American trip,[222] and said Guaidó would be barred from running for public office for fifteen years.[223][224] The comptroller general is not a judicial body; according to constitutional lawyer José Vicente Haro, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights ruled in 2011 that an administrative body cannot disallow a public servant from running. Constitutional law expert Juan Manuel Raffalli stated that Article 65 of Venezuela's Constitution provides that such determinations may only be made by criminal courts, after judgment of criminal activity.[225]

Red Cross aid effort

[edit]

In March, Francesco Rocca, president of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, announced that the Red Cross was preparing to bring humanitarian aid to the country in April to help ease both the chronic hunger and the medical crisis.[226] The Wall Street Journal said that the acceptance of humanitarian shipments by Maduro was his first acknowledgement that Venezuela is "suffering from an economic collapse."[227][228] After a 9 April meeting with the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC),[229] Maduro indicated for the first time that he was prepared to accept international aid.[230] Guaidó called on Venezuelans to "stay vigilant to make sure incoming aid is not diverted for 'corrupt' purposes".[228]

Following the joint report from Human Rights Watch and Johns Hopkins in April 2019, increasing announcements from the United Nations about the scale of the humanitarian crisis, and the softening of Maduro's position on receiving aid, the ICRC tripled its budget for aid to Venezuela.[231] The first Red Cross delivery of supplies for hospitals arrived on 16 April, offering an encouraging sign that the Maduro administration would allow more aid to enter.[232] According to The New York Times, "armed pro-government paramilitaries" fired weapons to disrupt the first Red Cross delivery, and officials associated with Maduro's party told the Red Cross to leave.[233]

According to the Associated Press, having long denied that there was a humanitarian crisis in Venezuela, Maduro positioned the delivery "as a necessary measure to confront punishing U.S. economic sanctions." Having "rallied the international community", Guaidó "quickly claimed credit for the effort."[234]

Revocation of Guaidó's parliamentary immunity

[edit]Chief justice Maikel Moreno asked that the Constituent Assembly (ANC), controlled by Maduro loyalists, remove Guaidó's parliamentary immunity as president of the National Assembly,[235][236] moving the Maduro administration a step closer towards prosecuting Guaidó.[237] Guaidó supporters disagree that the Maduro-backed institutions have the authority to ban Guaidó from leaving the country and consider acts of the ANC "null and void".[235] The Venezuelan Constitution provides that only the National Assembly can bring the president to trial by approving the legal proceeding in a "merit hearing".[235] On 2 April, after the ANC voted to remove his parliamentary immunity, Guaidó promised to continue fighting "Maduro's 'cowardly, miserable and murderous' regime."[238]

Military uprising attempt

[edit]

On 19 April, Guaidó called for a "definite end of the usurpation" and the "largest march in history" on 1 May.[239] Coinciding with his speech, NetBlocks stated that state-run CANTV again blocked access to social media in Venezuela.[240] On 30 April 2019, Leopoldo López, who was held under house arrest by the Maduro administration, was freed on orders from Guaidó.[241] The two men, flanked by members of the Venezuelan armed forces near La Carlota Air Force Base in Caracas, announced an uprising,[242] stating that this was the final phase of "Operation Freedom".[243] Though Guaidó said his forces held La Carlota, when supporters approached the base, Guaidó and a few dozen supporters stayed in a nearby overpass outside.[244]

Maduro was not seen during the day,[245] but he appeared with his Defense Minister Padrino on that evening's televised broadcast,[246] and announced he would replace Manuel Cristopher Figuera, Director General of the Bolivarian Intelligence Service (SEBIN), who had broken with Maduro during the uprising,[247] saying it was time to "rebuild the country"[247] and that "scoundrels were plundering the country."[248] The United States said Maduro had prepared to leave Venezuela that morning, but Russia and Cuba helped convince him to stay.[245][249][250] Both Russia and Maduro denied that he had plans to leave Venezuela.[251]

Guaidó's supporters were forced to retreat by security forces using tear gas. Colectivos fired on protesters with live ammunition, and one protester was shot in the head and killed.[252][253] Human Rights Watch said it believed that "security forces fired shotgun pellets at demonstrators and journalists."[254] By the end of the day, one protester had died,[252] and López was at the Spanish embassy,[255] while about 25 military personnel received asylum in the Panamanian embassy in Caracas.[244][256]

Guaidó acknowledged he had received insufficient military backing,[254] but added that "Maduro did not have the support nor the respect of the Armed Forces"[257] and called for strikes beginning on 2 May, with the aim of a general strike later in the month.[253] Russia and the US each charged the other with interference in another country's affairs.[254]

Negotiations

[edit]Following the failed military uprising, momentum surrounding Guaidó had subsided and fewer supporters gathered at demonstrations, with Guaidó resorting to negotiations with Maduro.[258] Guaidó's deputy chief Rafael Del Rosario acknowledged that the debacle on 30 April made the prospect of removing Maduro more difficult.[258] Beginning negotiations was a setback for Guaidó's movement,[258][259] with the Associated Press stating, "Participation in the mediation effort is a reversal for the opposition, which has accused Maduro of using negotiations between 2016 and 2018 to play for time".[259] According to the New York Times, years of difficulties has made Maduro "adept at managing, if not solving, cascading crises",[258] while Phil Gunson of the International Crisis Group stated that despite facing issues, Maduro "must be very pleased that he is now in the driving seat", with the ability to use the actions of Guaidó and international actors for propaganda purposes.[260] By May 2019, Trump had decided that Guaidó was weak; Bolton attributed a change of Trump's position to a comment made by President of Russia Vladimir Putin to Trump in a phone call that Guaidó's claim to the presidency would be the equivalent of Hillary Clinton declaring herself president following the 2016 United States presidential election.[244]

Representatives of Guaidó and Maduro began mediation with the assistance of the Norwegian Centre for Conflict Resolution (NOREF), with Jorge Rodríguez and Héctor Rodríguez serving as representatives for Maduro while Gerardo Blyde and Stalin González were representatives for Guaidó.[259][261] Guaidó confirmed that there was an envoy in Norway, but assured that the opposition would not take part in "any kind of false negotiation" and that talks must lead to Maduro's resignation, a transitional administration and free and fair elections.[259][261]

In July 2019, Norway's commission carried out a third round of discussions between Guaidó's and Maduro's representatives in Barbados.[262] By August 2019, the Maduro administration decided to halt talks with Guaidó's commission after Trump administration imposed new additional sanctions on Venezuela, ordering a freeze on all Venezuelan government assets in the United States and barred transactions with US citizens and companies.[263]

Second visit of the OHCHR

[edit]Ahead of a three-week session of the UN Human Rights Council, the OHCHR chief, Michelle Bachelet, visited Venezuela from 19 to 21 June.[264] The Human Rights Commissioner met separately with both Maduro and Guaidó during her visit, as well as with Maduro's Attorney General Tarek William Saab, several human right activists, and families of victims who experienced torture and state repression.[264][265] Protests occurred in front of the UN office in Caracas during the last day of the visit, denouncing rights abuses carried out by Maduro's administration.[265] Gilber Caro, who was released two days before the visit, joined the protest.[266] Bachelet announced the creation of a delegation maintained by two UN officials that will remain in Venezuela to monitor the humanitarian situation.[265] Bachelet expressed concern that the recent sanctions on oil exports and gold trade could worsen the crisis that has increased since 2013,[265][267] calling the measures "extremely broad" and that they are capable of exacerbating the suffering of the Venezuelan people.[268] She also called for the release of political prisoners in Venezuela.[264] This was the first time a United Nations High Commissioner of Human Rights visited Venezuela.[267]

The final published report addressed the extrajudicial executions, torture, forced disappearances and other human rights violations reportedly committed by Venezuelan security forces in the recent years.[269] Bachelet expressed her concerns for the "shockingly high" number of extrajudicial killings and urged for the dissolution of the Special Action Forces (FAES).[270] According to the report, 1,569 cases of executions as consequence as a result of "resistance to authority" were registered by the Venezuelan authorities from 1 January to 19 March.[270] Other 52 deaths that occurred during 2019 protests were attributed to colectivos.[271] The report also details how the Venezuelan government "aimed at neutralising, repressing and criminalising political opponents and people critical of the government" since 2016.[270]

Guaidó supported the investigation, stating "the systematic violation of human rights, the repression, the torture... is clearly identified in the (UN) report".[269] Maduro administration described the report as a "biased vision" and demanded it be "corrected".[272] In the words of his foreign minister, "It's a text lacking in scientific rigor, with serious errors in methodology and which seems like a carbon copy of previous reports".[272] Maduro would later state that the OHCHR "has declared itself an enemy" to Maduro and the Bolivarian Revolution.[273]

Speaking to reporters after the UN Human Rights Council, Bachelet announced the release of 22 Venezuelan prisoners, including 20 students, judge Maria Lourdes Afiuni, in her second house arrest since March, and journalist Braulio Jatar, arrested in 2016.[274] Bachelet welcomed the conditional releases and the acceptance of the two officers delegation as "the beginning of positive engagement on the country's many human rights issues".[274]

In October 2019, Venezuela competed for one of the two seats to the United Nations Human Rights Council, along with Brazil and Costa Rica, and was elected with 105 votes in a secret ballot by the 193-member United Nations General Assembly. Brazil was re-elected with 153 votes, while Costa Rica was not having garnered 96 votes and entering the month of the election as competition to Venezuela. The United States, Lima Group and human rights groups lobbied against Venezuela's election.[275]

On 16 September 2020, the United Nations accused the Maduro government of crimes against humanity.[276]

Torture and death of Acosta Arévalo

[edit]On 26 June, Maduro said that his government had arrested several defecting military, thus foiling a plot to remove him from power and to assassinate him, his wife and Diosdado Cabello.[277][278] The alleged plan also included the rescue of Raúl Baduel, a retired general imprisoned for a second time in 2017, to install him as president.[278][277] Maduro accused Israel, Colombia, Chile and the United States of involvement in the plot.[278][279] Jorge Rodríguez said that the foiled plan involved the bombing of a government building, the seizing of La Carlota air base, and a bank robbery.[277] Guaidó dismissed the allegations as lies;[278] opposition members have frequently accused Maduro of coercion of arrested suspects and fabrication of plots for political gain.[278][280]

In the wake of the coup allegations, an alleged kidnapping attempt directed at members of Guaidó's entourage occurred on a Caracas highway.[281] Eight armed men on motorcycles dressed as civilians allegedly surrounded a vehicle containing two of Guaidó's aides.[281][282] Guaidó, who was in a car further ahead, spoke with the armed civilians,[280] according to photos and a video released by his press team[282] and published by Infobae.[283] According to Guaidó, the group received orders from the Venezuelan Military Counter-intelligence agency DGCIM, but were not "hostile".[282][280]

Navy captain Rafael Acosta Arévalo, who had been arrested on charges related to the alleged foiled coup attempt and transferred to a military hospital, died during detention on 28 June.[284] Maduro administration did not provide a cause of death but announced an investigation on the matter.[285] Acosta Arevalo's wife, human rights advocates, Juan Guaidó and the US Department of State accused Maduro's administration of torturing the captain to death.[284] The Lima Group and the European Union called for an independent investigation.[286] The preliminary autopsy determined that Acosta Arévalo's cause of death was "severe cerebral edema [brain swelling] caused by acute respiratory failure caused by a pulmonary embolism caused by rhabdomyolysis [a potentially life-threatening breakdown of muscle fibers] by multiple trauma".[287]

Operación Alacrán

[edit]The conditions for any political change in 2020 are getting ever more remote.

An investigation led by Armando.info reported that nine members of the National Assembly defended individuals sanctioned by the United States for their involvement in the controversial Local Committees for Supply and Production (CLAP) program. The investigation reported that the implicated lawmakers had written letters of support to the United States Treasury and others to a Colombian man named Carlos Lizcano, who authorities were investigating over his possible links to Alex Saab, a Colombian businessman associated with the food distribution program and under United States sanctions. According to Armando.info, the lawmakers wrote the letters despite being aware of evidence that tied Lizcano to Saab.[28] Guaidó condemned the actions of the nine legislators, suspending them from their positions and stating that it was "unacceptable to use a state institution to attempt to whitewash the reputation of thieves".[28] The scandal damaged Guaidó's reputation among his supporters in Venezuela, with some members of the opposition beginning to call for new leadership, according to analysts and those involved.[28]

The Maduro government increased its pressure by "deploying bribes, intimidation and repression" attempting to divide the opposition to maintain power.[288]

Dollarization

[edit]Following increased sanctions throughout 2019, the Maduro government abandoned policies established by Chávez such as price and currency controls.[9] In a November 2019 interview with José Vicente Rangel, President Maduro described dollarization as an "escape valve" that helps the recovery of the country, the spread of productive forces in the country and the economy. However, Maduro said that the Venezuelan bolívar would still remain as the national currency.[289] The Economist wrote that Venezuela had also obtained "extra money from selling gold, both from illegal mines and from its reserves, and narcotics".[9] Its article continued to explain that the improving economy led to more difficulties for Guaidó as Venezuelans who had a better situation were less likely to protest against Maduro.[9]

2020 events

[edit]Internal parliamentary election disrupted

[edit]The 2020 Venezuelan National Assembly Delegated Committee election of 5 January, to elect the Board of Directors of the National Assembly was disrupted. The events resulted in two competing claims for the Presidency of the National Assembly: one by Luis Parra and one by Juan Guaidó.[290] Parra was formerly a member of Justice First, but was expelled from the party on 20 December 2019 based on the Operación Alacrán corruption allegations, which he denied. From inside the legislature, Parra declared himself president of the National Assembly, a move that was welcomed by the Maduro administration.[291] The opposition disputed this outcome, saying that quorum had not been achieved and that no votes were counted.[291] Police forces had blocked access to parliament to some opposition members, including Guaidó and journalists. Later in the day, a separate session was carried out at the headquarters of El Nacional newspaper, where 100 of the 167 deputies voted to re-elect Guaidó as president of the parliament.[291]

Guaidó was sworn in a session on 7 January after forcing his way in through police barricades. On the same day, Parra reiterated his claim to the parliament's presidency.[292]

Russia is the only foreign government to have officially recognized Luis Parra's investiture, while the European Union, the United States, Canada, and most Latin American countries recognized Guaidó's re-election.[293]

Guaidó second international tour

[edit]On 19 January, Guaidó once again exited Venezuela and arrived in Colombia, planning to meet with Mike Pompeo, as well as traveling to Europe and the United States later, defying his exit prohibition for a second time.[294] Guaidó travelled to Brussels, Belgium, and on 22 January met with Margaritis Schinas, Vice-President of the European Commission, and Josep Borrell, High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs.[295] On 23 January, Guaidó participated in the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland.[296] During his trip in Europe, Guaidó also met with Boris Johnson, Emmanuel Macron,[297] and Angela Merkel.[298] Afterwards, Guaidó travelled to Canada and met with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.[299] On February 4, he was invited to President Donald Trump's 2020 State of the Union address to Congress, and was applauded by the crowd, which was composed of members of both Democratic and Republican parties.[300]

Diosdado Cabello declared that "nothing" would happen to Guaidó when he returned to Venezuela.[301] After meeting with Donald Trump in the White House, Constituent Assembly member Pedro Carreño said that if Guaidó wanted to come back as "commander-in-chief", "we will receive him with this peinilla", hitting his podium with a machete.[302] Guaidó was allowed back into Venezuela by officials through Simón Bolívar International Airport on 12 February, despite the travel ban imposed by Maduro's government.[303]

Security forces installed an anti-aircraft gun in the Caracas-La Guaira highway and blocked the highway;[304] opposition deputies had to reach the airport on foot to receive Guaidó. Due to the block, several ambassadors were also unable to go to the airport. Upon Guaidó's arrival at the Simón Bolívar International Airport, around two hundred Maduro supporters surrounded and jostled Guaidó, his wife Fabiana Rosales and several opposition deputies that waited for him at the airport. Some journalists were also attacked and had their equipment stolen by the group. Tens of military and police officials were present and did not intervene to prevent the attack. Several passengers declared to local outlets that Maduro's administration sent a group of pro-government activists to insult and harass the opposition members with impunity, including employees of the recently sanctioned Conviasa airline.[305] The Inter American Press Association condemned the attacks on the journalists.[306]

The following day, the opposition and relatives denounced that Guaidó's uncle, Juan José Márquez, had been missing for 24 hours after receiving his nephew in the airport, blaming Maduro's government. His wife declared that Márquez was detained in the migration area and that his whereabouts were unknown.[307] Afterwards, in his television talk show Con El Mazo Dando, Diosdado Cabello accused Márquez of carrying explosives when he landed in Venezuela. Hours later, a court formalized Márquez's detention, copying Cabello's accusations. Márquez was detained in the Caracas headquarters of the Directorate General of Military Counterintelligence, despite him being a civilian.[308]

Barquisimeto shooting

[edit]On 29 February Juan Guaidó mobilized a march against the government of Nicolás Maduro in the Juan de Villegas parish, Barquisimeto, Lara state. The day of the march, pro-government colectivos shot at Guaidó, who was in a van at the time of the shooting. Bolivarian National Intelligence Service agents were also reported of having participated in the attack.[309] Guaidó's vehicle received nine gunshots and the shooting left a total of ten wounded.[309][310]

COVID-19 pandemic

[edit]The COVID-19 pandemic was confirmed to have spread to Venezuela on 13 March, when the Maduro administration announced the first two cases.[311] On 16 March, Maduro reversed the country's official position against the International Monetary Fund (IMF), asking the institution for US$5 billion to combat the pandemic,[312] a first during Maduro's presidency, being a critic of the institution.[313][314] The IMF rejected the deal as it was not clear, among its member states, on who it recognizes as Venezuela's president.[315] According to a report by Bloomberg, the Maduro administration also tried to request aid of $1 billion from the IMF after the first request was denied.[316] Guaidó called for the creation of a "national emergency government", not led by Maduro, on 28 March. According to Guaidó, a loan of US$1.2 billion was ready to be given in support of a power-sharing coalition between pro-Maduro officials, the military and the opposition in order to fight the pandemic in Venezuela. If accepted, the money would go to assist families affected by the disease and its economic consequences.[317]

US Department of Justice indictment

[edit]

On 26 March, the US Department of State offered $15 million on Nicolás Maduro, and $10 million each on Diosdado Cabello, Hugo Carvajal, Clíver Alcalá Cordones and Tareck El Aissami, for information leading to their arrest in relation to charges of drug trafficking and narco-terrorism.[318] Maduro had been offering to hold talks with the opposition about handling the outbreak in the country shortly before the indictment and then called them off.[319][320][321][322]

After being indicted, retired general Clíver Alcalá in Colombia published a video claiming responsibility for a stockpile of weapons and military equipment seized in Colombia.[323] According to Alcalá, he had made a contract with Guaidó and "American advisers" in order to buy weapons to remove Maduro.[323] Alcalá did not present any evidence[323] and Guaidó rejected the allegations.[324] After wishing farewell to his family, Alcalá surrendered to US authorities on 27 March.[325]

Transitional government proposals

[edit]On 31 March, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said that sanctions did not apply to humanitarian aid during the COVID-19 pandemic in Venezuela and that the US would lift all sanctions if Maduro agreed to organize elections that did not include himself in a period of six to twelve months. Pompeo reiterated US support for Juan Guaidó.[326] The US proposed a transitional government that would exclude both Maduro and Guaidó from the presidency.[327] The deal would enforce a power-sharing scenario between the different government factions. Elections would have to be held within the year, and all foreign militaries, particularly Cuba and Russia, would have to leave the country. The US were still seeking Maduro's arrest at the time of the announcement.[328] Other aspects of the US deal would include releasing all political prisoners and setting up a five-person council to lead the country; two members each chosen by Maduro and Guaidó would sit on the council, with the last member selected by the four. The European Union also agreed to remove sanctions if the deal went ahead. Experts have noted that the deal is similar to earlier proposals but explicitly mentions who would lead a transitional government, something which stalled previous discussions, and comes shortly after the US indicted Maduro, which might pressure him to peacefully leave power.[329] Guaidó accepted the proposal[330] while Venezuela's foreign minister Jorge Arreaza rejected it and declared that only parliamentary elections would take place in 2020. Arreaza said that "decisions about Venezuela would be made in Caracas and not in Washington or other capitals" and that "the most important transition for Venezuela was the one started many years ago from capitalism to socialism."[undue weight? – discuss][331]

After various members of Guaidó's team were arrested on 30 March, Guaidó denounced a new wave of attacks against him.[332] Following that, Attorney General Tarek William Saab called Juan Guaidó to appear before the Public Ministry on 2 April based on Alcalá's accusations.[333] Guaidó did not accept to appear before the public prosecutor.[333] The day of the citation, two more members of Guaidó's office were arrested, charged for alleged "attempted coup d'etat" and "magnicide".[333] Guaidó's team reported that "With this new assault by the dictatorship, there are now 10 [of its] members that have been detained by security forces. Five of them in the last 72 hours."[333]

Reuters reported that during the pandemic allies of both Nicolás Maduro and Juan Guaidó had secretly begun exploratory talks, according to sources on both sides.[334] Guaidó and US Special Representative for Venezuela Elliott Abrams have denied that negotiations have taken place.[335][336] The Associated Press reported that the National Assembly agreed to establish a monthly $5,000 salary for the lawmakers funded from an $80 million "Liberation Fund" made up of Venezuelan assets seized by the Trump administration. Guaidó's communications team issued a statement denying that such salary had been approved, saying that lawmakers have gone unpaid since Maduro cut off funding after the opposition won the legislature in 2015 and that the deputies would determine an appropriate, as well as communicating it transparently. It also said that the $14 million in funding destined for the National Assembly would cover not only the deputies' personal income, but also office expenses, staff costs, travel and other related legislative expenses.[337]

Operation Gideon

[edit]Eight former Venezuelan soldiers were killed and seventeen rebels were captured on 3 May, including two American security contractors, after approximately 60 men landed in Macuto and tried to invade Venezuela. The members of the naval attack force were employed as private military contractors by Silvercorp USA and the operation aimed to depose Maduro from power.[338]

Parliamentary election

[edit]The opposition parties that make up the Democratic Unity Roundtable coalition agreed unanimously not to participate in the election, stating the reason as irregularities and their complaints during the planning of the process and arguing that it was likely the election would be fraudulent. Twenty-seven political parties signed the agreement, including the four largest opposition parties Popular Will, Justice First, Democratic Action and A New Era.[339][340][341]

The opposition criticized the appointment of the members of the National Electoral Council by the Supreme Tribunal, stating that it is under the purview of the National Assembly, and at least seven political parties had their board of directors suspended or replaced by the pro-government Supreme Tribunal of Justice, including Popular Will, Justice First, Democratic Action,[342] and Copei, as well as left-wing political parties, including Tupamaro,[343] Fatherland for All,[344] and Red Flag.[345] Opposition politicians Henrique Capriles and Stalin González initially encouraged participation in the elections. They later withdrew and demanded better electoral conditions.[346]

The Lima Group, the International Contact Group, the European Union and the United States rejected holding parliamentary elections in 2020, insisting in the necessity of holding elections "with free and fair conditions".[347] The International Contact Group, headed by Uruguay, stated the formation of the Electoral Council "undermines the credibility of the next electoral process."[347] The Organization of American States (OAS) stated the appointment of the Electoral Council was "illegal", rejecting it, and further stated that independent bodies are needed for "transparent, free and fair" elections to take place in the country.[348] In July, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, headed by Michelle Bachelet, said that "the recent decisions of the Supreme Tribunal of Justice diminish the possibility to build conditions for democratic and credible electoral processes" and "appoint new National Electoral Council rectors without the consensus of all the political forces."[349][350]

2021 events

[edit]As a response to the position of the Popular Will party of focusing on a timetable for presidential, parliamentary and regional elections, Leopoldo López said that "telling us from Europe that we are maximalist because we want freedom is a colonialist comment [...] that we should renounce our dream of freedom when you already have it."[351]

On 5 August 2021, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador announced that Mexico would host talks between the Maduro government and the political opposition.[352]

2022 events

[edit]San Carlos attack

[edit]On 11 June 2022, pro-government followers attacked Guaidó after an opposition march in San Carlos, Cojedes state, throwing objects at him and violently removing him from the restaurant he was holding a meeting in. Nosliw Rodríguez, former PSUV deputy and candidate for the Cojedes governorship, was identified as one of the people that led the attack against Guaidó.[353]

Interim government dissolution

[edit]On 30 December 2022, three of the four main political parties (Justice First, Democratic Action and A New Era) backed a reform of the Statute for the Transition to Democracy to dissolve the interim government and create a commission of five members to manage foreign assets,[33][34] stating that the interim government had failed to achieve the goals it had set.[35] The amendment was voted by the opposition National Assembly as deputies sought a united strategy ahead of the presidential elections scheduled for 2024. The reform was approved with 72 votes in favor, 29 against and 8 abstentions.[33][34]

Recognition, reactions, and public opinion

[edit]

At his peak, Guaidó's claim as the interim president of Venezuela was recognized 57 countries,[354] "including the US, Canada and most Latin American and European countries".[355] Other countries were divided between a neutral position, support for the National Assembly in general without endorsing Guaidó, and support for Maduro's presidency; internationally, support followed traditional geopolitical lines, with Russia, China, Iran, Syria, Cuba, and Turkey supporting Maduro, and the US, Canada, and most of Western Europe supporting Guaidó.[13][356]

The European Parliament recognized Guaidó as interim president.[357][358] In 2019, the European Union unanimously recognized the National Assembly,[359] but Italy dissented on recognizing Guaidó.[360] In January 2021, the European Union stopped recognizing Guaidó's claim, but still did not recognize Maduro as the legitimate president;[29][361] the European Parliament reaffirmed its recognition of Guaidó as president,[30][31] and the EU threatened with further sanctions.[29]

The OAS approved a resolution on 10 January 2019 "to not recognize the legitimacy of Nicolás Maduro's new term".[362] In a 24 January special OAS session, sixteen countries including the US recognized Guaidó as interim president, but they did not achieve the majority needed for a resolution.[363] The United Nations called for dialogue and deescalation of tension, but could not agree on any other path for resolving the crisis.[364] Twelve of the fourteen members of the Lima Group recognize Guaidó;[365] Beatriz Becerra—on the day after she retired as head of the human rights subcommittee for the European Parliament—said that the International Contact Group, jointly sponsored by Uruguay and Mexico, had been of no use and "has been an artifact that has served no purpose since it was created". She said there had been no progress on the 90-day deadline for elections that the group established when it was formed, and she considered that the Contact Group should be terminated and efforts coordinated through the Lima Group.[366] During the 49th General Assembly of the Organization of American States, on 27 June, Guaidó's presidency was recognized by the organization.[8]

The Venezuelan Observatory of Social Conflictivity stated that there were on average 69 protests daily in Venezuela during the first three months of 2019, for a total of 6,211 protests, representing a significant increase over previous years (157% of protests for the same period in 2018, and 395% relative to the number in 2017).[367]

Following the failed uprising on 30 April, support for Guaidó declined, attendance to his demonstrations subsided and participants in committees organized by Guaidó stated that there has been little progress.[368][369] Reuters reported in June that analysts have predicted that Maduro would maintain his position as he gains confidence that his actions against the opposition go "relatively unpunished".[368]

By the end of 2019, support for Guaidó dropped, with protests organized by his movement resulting with low participation.[26][27][28][370] Pollster Datanálisis published figures showing that support for Guaidó decreased from 61% in February to 42% in November 2019.[28] According to Jesús Seguías, the head of the Venezuelan analysis firm Datincorp, "For years Washington and the Venezuelan opposition have said that Nicolás Maduro, and before him Hugo Chávez, were weak and about to fall [...] but it's clear that's not the case".[371] Analyst Carlos Pina stated that as "[t]he military support to President Maduro remains intact", the opposition will need to "rethink its strategy" and that "Guaidó has also been very limited in suggesting or proposing a strategy that could change the current [status quo]."[27] Into December 2019, Venezuelan pollster Meganálisis surveys showed that 10% of respondents approved of Guaidó, compared to 9% who supported Maduro.[372]

As of January 2023, following the opposition vote to dissolve Guaidó's interim government, the United States stopped recognizing Guaidó's presidential claim. A spokesperson for the White House and State Department said that the US "recognized the National Assembly elected in 2015, which Guaidó had led, as Venezuela's 'only remaining democratically elected institution'."[12]

Defections

[edit]The Miami Herald reported that dozens of arrests were made in anticipation of a military uprising, and Defense Minister Vladimir Padrino López ordered a counterintelligence effort to locate conspirators or possible defectors.[373] According to France 24, Maduro declared "military deserters who fled to Colombia have become mercenaries" as part of a "US-backed coup".[374] Guaidó declared that the opposition had held secret meetings with military officials to discuss the Amnesty Law.[375]

Hugo Carvajal, the head of Venezuela's military intelligence for ten years during Hugo Chávez's presidency and "one of the government's most prominent figures",[376] publicly broke with Maduro and endorsed Guaidó as acting president.[377] During the 30 April 2019 uprising attempt, Manuel Cristopher Figuera, the Director General of Venezuela's National Intelligence Service, SEBIN, broke with Maduro.[248][247]

Certain top military figures recognized Guaidó,[378][379] and around 1,400 military personnel have defected to Colombia, but the top military command stays loyal to the government.[380]

Following the 23 January events, some Venezuelan diplomats in the United States supported Guaidó; the majority returned to Venezuela on Maduro's orders.[381]

Foreign military involvement

[edit]

In early 2019, with Cuban and Russian-backed security forces in the country, United States military involvement became the subject of speculation.[383] Senior U.S. officials have declared that "all options are on the table",[384] but they have also said that "our objective is a peaceful transfer of power".[385] Colombian guerrillas from National Liberation Army (ELN) have vowed to defend Maduro, with ELN leaders in Cuba stating that they have been drafting plans to provide military assistance to Maduro.[386]

Article 187 of the Venezuelan Constitution provides that "[i]t shall be the function of the National Assembly: (11) To authorize the operation of Venezuelan military missions abroad or foreign military missions within the country."[81][384] In every demonstration summoned by Guaidó, there have been numerous signs demanding the application of Article 187, and a March poll showed 87.5% support for foreign intervention.[h][384][387] Venezuelan politicians such María Corina Machado and Antonio Ledezma, former mayor of Caracas, have also demanded the application of the article.[384]

According to Giancarlo Fiorella, writing in Foreign Affairs, the "loudest calls for intervention are coming not from the White House and its media mouthpieces but from some members of the Venezuelan opposition and from residents of the country desperate for a solution—any solution—to their years-long plight."[384] Fiorella states that "talk of invoking article 187(11) has become commonplace" in Venezuela, adding that "the push for a military intervention in Venezuela is most intense not among hawks in Washington but inside the country itself."[384]

Guaidó has said he would call for intervention "when the time comes", but in media interviews, he has not stated he supports removing Maduro by force.[384] The National Assembly approved in July 2019 the reincorporation of Venezuela to the Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance, a mutual defense pact signed in 1947 that has never been enacted and from which Venezuela retired in 2013.[388][389] Venezuela's reincorporation to the pact "can be used to request military assistance against foreign troops inside the country."[390]

In a 4 December 2019 interview with Vox, Guaidó stated: "We sense a firm commitment from the United States. [...] I think they're doing everything they could be doing under these circumstances, as are Colombia and Brazil."[391] When asked if he was nearer from removing Maduro from power than in January 2019, Guaidó replied: "Absolutely. Back then we didn't have multiple countries recognizing and supporting us. [...] Today, we have way more tools at our disposal than we did one year ago."[391] Bloomberg News reported two days later that the Trump administration began to doubt that an opposition led by Guaidó would remove Maduro from office.[16] The United States reportedly had no military option regarding Venezuela, although it began to debate on whether to partner with Russia to encourage Maduro to leave office or to increase pressure on Cuba, which is the Maduro government's main supporter.[16]

Cuban presence

[edit]According to professor Erick Langer of Georgetown University, "Cuba and Russia have already intervened."[383] A Cuban military presence of at least 15,000 personnel was in Venezuela in early 2018,[392] while estimates ranging from hundreds to thousands of Cuban security forces were reported in 2019.[383] In April 2019, Trump threatened a "full and complete embargo, together with highest-level sanctions" on Cuba if its troops do not cease operations in Venezuela.[393]

Russian presence

[edit]Two nuclear weapon-capable Russian planes landed in Venezuela in December 2018 in what Reuters called a "show of support for Maduro's socialist government."[394]

According to the Kremlin, there are about 100 Russian military personnel in Venezuela "to repair equipment and provide technical co-operation".[395] On 23 March 2019, two Russian planes landed in Venezuela carrying 99 troops[396] and 35 tonnes of matériel.[394] Alexey Seredin from the Russian Embassy in Caracas said the two planes were "part of an effort to maintain Maduro's defense apparatus, which includes Sukhoi fighter jets and anti-aircraft systems purchased from Russia."[396]

National Assembly deputy Williams Dávila said the National Assembly would investigate the "penetration of foreign forces in Venezuela."[397]

Assets and reserves

[edit]Venezuela's third-largest export (after crude oil and refined petroleum products) is gold.[398] The World Gold Council reported in January 2019 that Venezuela's foreign-held gold reserves had fallen by 69% to US$8.4 billion during Maduro's presidency.[399] In 2018, Maduro's government exported $900 million worth of gold out of Venezuela into Erdoğan's Turkey.[400][401] In April 2019, Rubio warned the United Arab Emirates and Turkey not be "accomplices" in the "outrageous crime" of exporting Venezuela's gold.[402]

In mid-December 2018, a Venezuelan delegation went to London to arrange for the Bank of England to return the $1.2 billion in gold bullion that Venezuela stores at the bank. Unnamed sources told Bloomberg that the Bank of England declined the transfer due to a request from US Secretary of State Pompeo and National Security Adviser Bolton, who wanted to "cut off the regime from its overseas assets".[403] In his memoir The Room Where It Happened, Bolton said UK Foreign Minister Jeremy Hunt was "delighted to cooperate on steps they could take, for example freezing Venezuela's gold deposits in the Bank of England, so the regime could not sell the gold to keep itself going".[404] In an interview with the BBC, Maduro asked Britain to return the gold instead of sending humanitarian aid, saying that the gold was "legally Venezuela's, it belongs to the Central Bank of Venezuela" and could be used to solve the country's problems. Guaidó asked the British government to ensure that the Bank of England does not provide the gold to the Maduro government. Maduro also said that the US has frozen $10 billion in Venezuelan accounts through its sanctions.[405]

In mid-February 2019, a National Assembly legislator Ángel Alvarado said that eight tonnes of gold worth over US$340 million[398] had been taken from the vault while the head of the Central Bank was abroad.[406] In March, Ugandan investigators reported that the gold could have been smuggled into that country.[407] Government sources said another eight tonnes of gold was taken out of the Central Bank in the first week of April 2019; the government source said that there were 100 tonnes left. The gold was removed while minimal staff was present and the bank was not fully operational because of the ongoing, widespread power outages; the destination of the gold was not known.[408][409]

In 2009, Venezuela's foreign reserves peaked at US$43 billion; by July 2017, they had fallen below $10 billion "for the first time in 15 years",[410] and as of March 2019, they had dropped to US$8 billion.[411] About two-thirds of Venezuela's reserves are in gold.[412] Part of Venezuela's remaining reserves are held by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in financial instruments called SDRs. In 2018, Venezuela had almost $1 billion in IMF SDRs, but it had drawn US$600 million in one year. To access SDR reserves, IMF rules require than a government be recognized by a majority of IMF members, and there is no majority recognition for either man claiming the Venezuelan presidency; the IMF denied Maduro access to the remaining US$400 million—"one of the regime's last remaining sources of cash" according to Bloomberg.[412] The IMF has not recognized Guaidó;[413] Ricardo Hausmann—Guaidó's representative recognized by the Inter-American Development Bank—said the "IMF is safeguarding the assets until a new government takes over. 'Those funds will be available when this usurpation ends.'" The US has given Guaidó control of "key Venezuelan bank accounts",[412] and has said it will give Guaidó control of US assets once his administration is in power.[405]

The Portuguese bank Novo Banco stopped Maduro's attempt to transfer over US$1 billion[414] through BANDES subsidiary, Banco Bandes Uruguay, in early 2019.[citation needed] Over two months later, Maduro responded that Portugal had illegally blocked the money, and asked that it be returned to buy food and medicine.[415]

In 2020, the English High Court ruled in favor of Juan Guaidó in a hearing over whether Guaidó or Nicolás Maduro should control $1 billion of its gold stored in the Bank of London.[416]

In 2022, the United Kingdom Supreme Court ruled in favor of Juan Guaidó again regarding the control of the gold stored in the Bank of London.[417][418]

Sanctions

[edit]

During the crisis in Venezuela, the United States, Canada, Mexico, Panama, Switzerland individually, and the countries of the European Union collectively, have applied sanctions against people associated with Maduro's administration, including government officials, members of the military and security forces, and private individuals.[419] As of 27 March 2018, the Washington Office on Latin America said 78 Venezuelans associated with Maduro had been sanctioned by several countries.[420]

On 15 January 2019, the National Assembly approved legislation to work with dozens of foreign countries to request that these nations freeze Maduro administration bank accounts.[110]

Through April 2019, the U.S. sanctioned more than 150 companies, vessels and individuals, in addition to revoking visas of 718 individuals associated with Maduro.[421]

Christian Krüger Sarmiento, director of Colombia Migration, announced on 30 January 2019 that the Colombian government maintained a list of people banned from entering Colombia or subject to expulsion. As of January 2019, the list had 200 people with a "close relationship and support for the Nicolás Maduro regime", but Krüger said the initial list could increase or decrease.[422]

As the humanitarian crisis deepened and expanded, the Trump administration levied more serious economic sanctions against Venezuela.[419] In January 2019, during the presidential crisis, the United States imposed sanctions on the Venezuelan state-owned oil and natural gas company PDVSA to pressure Maduro to resign.[423]

On 15 April 2019, Canada announced that another round of sanctions on 43 individuals were applied on 12 April based on the Special Economic Measures Act.[424] The government statement said those sanctioned are "high ranking officials of the Maduro regime, regional governors and/or directly implicated in activities undermining democratic institutions".[425]

The United States Department of the Treasury has also placed restrictions on transactions with digital currency emitted by or in the name of the government of Venezuela, referencing "Petro", a DIGITAL token.[426] and on Venezuela's gold industry.[427] After the detention of Guaidó's chief of staff, Roberto Marrero, in March 2019, the US also sanctioned the Venezuelan bank BANDES and its subsidiaries.[428]

The Treasury Department sanctioned seven additional individuals for their involvement in the disputed internal parliamentary elections of the National Assembly in January 2020.[429]

An October 2020 report published by the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA) by Venezuelan economist Luis Oliveros found that "while Venezuela's economic crisis began before the first U.S. sectoral sanctions were imposed in 2017, these measures 'directly contributed to its deep decline, and to the further deterioration of the quality of life of Venezuelans' ". The report concluded that economic sanctions "have cost Venezuela's government as much as $31 billion since 2017"[430][431]

Censorship and media control

[edit]

The Venezuelan press workers union denounced that in 2019, 40 journalists had been illegally detained as of 12 March; the National Assembly Parliamentary Commission for Media declared that there had been 173 aggressions against press workers as of 13 March.[432] As of June 2019, journalists have been denied access to seven sessions of the National Assembly by the National Guard.[433]

Between 12 January and 18 January,[434][435] Internet access to Wikipedia (in all languages) was blocked in Venezuela[436][437] after Guaidó's page on the Spanish Wikipedia was edited to show him as president.[438] Later on 21 January, the day of the National Guard mutiny in Cotiza, Internet access to some social media was reported blocked for CANTV users. The Venezuelan government denied it had engaged in blocking.[439][440] During the 23 January protests, widespread Internet outages for CANTV users were reported.[441][442]

Live streams of the National Assembly sessions and Guaidó's speeches have been regularly disrupted for CANTV users.[443] Since 22 January, some radio programs have been ordered off air; other programs have been temporarily canceled or received censorship warnings, including a threat to close private television and radio stations if they recognized Guaidó as acting president or interim president of Venezuela.[444]